15) The early transhumanists

HG Wells (left), Gip Wells (centre) and Julian Huxley, the three authors of The Science of Life

This is the 15th entry in my Spiritual Eugenics project, which looks at the overlap between New Age spirituality and eugenics. For a definition of these terms, an intro to the project, and preceding chapters, go here.

In this chapter, we will look at how Julian Huxley and his peers developed the religious creed which he would later call Transhumanism, and how their visions of scientific utopia inspired his brother’s humorous novel, Brave New World.

We left Julian in the 1920s, working in academia as a young biologist, recovering from a bad nervous breakdown, and looking for a new religion of humanity based on science and evolution. He was already showing signs of seeking a more public role than a life in the lab.

His first brush with fame came in 1920, when he published the findings of some experiments with axolotls, an amphibian creature with unusual capacities for regeneration. Unlike most amphibians, the axolotl doesn’t usually metaphorphosize into a land animal, remaining permanently juvenile and aquatic. Julian found he could induce metamorphosis by injecting the axolotl with ox thyroid. The Daily Mail declared that the young Huxley had discovered ‘the elixir of life’, to the embarrassment of Julian’s colleagues. His success raised an interesting question — could scientists discover a drug that speeds up humans’ metamorphosis into superhumans?

Another unusual foray from academia was Julian’s attempt at science fiction. In 1926, he published a short story called ‘The Tissue Culture King’, which would first appear in the Yale Review and then in the more pulpy Amazing Tales, alongside HG Wells’ War of the Worlds. In Julian’s story, the narrator comes across an African tribe, filled with biological monstrosities like two-headed frogs. He encounters a British man living with the tribe — Hascombe, who was ‘lately research worker at Middlesex Hospital’ and is now ‘religious advisor to King Mgbobe’ (note the similarity to Aldous’ last novel, Island, a utopia where the tribe’s religion is based on the theories of a visiting British scientist).

Deep in the jungle, Hascombe has developed a tribal religion based on his scientific research. He experiments with creating self-regenerating skin tissue (the narrator says this reminds him of the work of Alexis Carrel, on whom more shortly); he creates new species and experiments on growing humans in test-tubes. But he’s most excited by his experiments with hypnosis, trance and mass telepathy. ‘I’m after the super-consciousness…and I’ve already got the rudiments of it.’ Hascombe discovers he can induce a trance in the entire tribe and then transmit an order through mass telepathy. He has become a magical-scientific dictator. The narrator manages to escape, protecting himself from Hascombe’s telepathy machine by wearing a tin-foil hat (this is the origin of the classic conspiracy-theorist attire).

The story is revealing because it shows Julian imagining what an all-powerful scientist could achieve. Like TH Huxley and Francis Galton, he sees Science becoming the basis of a new religion for the dumb masses. He would always be attracted by this sort of top-down authoritarian project — one of his later books is called If I Were A Dictator (1934), in which he writes he would use every means to spread his philosophy of ‘scientific humanism’:

I shall develop to a high pitch the propaganda and public relations branch of my government departments, and after studying the various types of machinery for engendering mass enthusiasm and unified belief which have been tried during the last few years in Italy, Germany, Russia and the United States, I shall put my own selection into operation…

The Science of Life

In 1927, when he was 40, Julian astonished his academic colleagues by leaving the security of academia to become a freelance public scientist. He was lured by HG Wells, who invited him to collaborate on a new book project called The Science of Life. Wells’ popular introduction to world history, The Outline of History, had been a best-seller and he assured Julian that this book would sell just as well. It turned out to be a good move: Julian would become the most prominent public scientist of his generation, winning an Oscar for his 1934 wildlife documentary, The Private Life of Gannets, and co-presenting one of the most popular British radio shows of World War II (‘The Brains Trust’).

The Science of Life, published in 1931, was a 900-page guide to life on Earth, from the cell all the way to the ecosystem. It introduced the reading public to what the book calls ‘a fresh way of regarding life’ : the science of ecology.

The word ‘ecology’ was coined in 1866 by German biologist Ernst Haeckel, a friend of Darwin and TH Huxley. The field was developed in the 1920s-1940s by a group of biologists including several of Julian’s friends and students, such as Charles Elton, Alexander Carr-Saunders and Alister Hardy. They mapped what The Science of Life calls ‘the ecological web’ of energy flows, food chains and waste products stretching from the atmosphere to the soil.

The Science of Life explained this global ecological web, while at the same time warning that the delicate balance of the ecosystem was being sorely tested by the human population, which had grown from 1 billion in 1800 to 2 billion in 1900 (before soaring to 7 billion by the end of the 20th century).

Both HG Wells and Julian Huxley were members of the Malthusian League, which campaigned to lower population through birth control, and The Science of Life embraces Malthus’ bio-morality, declaring overpopulation is ‘biologically, a thoroughly evil thing’. The Science of Life warns of the ‘reckless’ use of natural resources like forests and coal, and bemoans the extinction of ‘magnificent creatures’ like the bison. It also warns that humanity is entering an era of pandemics, which are ‘the natural and inevitable result of over-crowding’.

Thus humans face the real threat of extinction. We need to bring ‘life under control’, and manage the ecosystem as efficiently as possible:

Man’s chief need to-day is to look ahead. He must plan his food and energy circulation as carefully as a board of directors plans a business. He must do it as one community, on a world-wide basis, and as a species…

This requires the evolution of ‘superindividual organisations’ of global governance, which would be steered by an elite of long-term-thinking technocrats. They would be the ‘new masters of the world’, in the words of Julian’s friend and fellow early environmentalist, Max Nicholson. This vision of global governance is precisely what emerged after World War Two, when Julian became first president of UNICEF, his colleague Sir John Boyd-Orr became the first head of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, and his friend Lord John Maynard Keynes helped to create the IMF and World Bank.

The need for a global reproduction policy

An essential part of bringing ‘life under control’ was bringing human reproduction under control. After all, over-population was ‘the fundamental evil out of which all the others that afflicted the race arose’, as Wells had put it in A Modern Utopia. Over-population threatened the ecosystem, exhausted the soil, drove species to extinction, made pandemics more likely, and above all, flooded the earth with ‘unfit’ humans.

Intelligence is hereditary, The Science of Life insists. ‘This is seen with especial clearness in the numerous cases — like the Cecils, or the Darwins — where intellectual ability runs in families’. At the moment, the stupid are outbreeding the smart, and there’s a dangerous increase ‘of idiots, imbeciles and the more dangerous because less obvious morons’.

The Science of Life doesn’t suggest particular races are less intelligent than others, but it does suggest there are ‘pockets of evil germ-plasm responsible for a large amount of vice, disease, defect and pauperism’. This genetic underclass threatens humanity with extinction: ‘The dead-weight of inferior population may overpower the constructive few.’

What is to be done? The Science of Life is warier of suggesting the extermination of the ‘unfit’ than Wells had been back in 1900. Instead, it says: ‘the problem of their elimination is a very subtle one, and there must be no suspicion of harshness or brutality…’ But clearly, the human species needs a ‘reproductive policy’. The book suggests that ‘low types’ might be bribed or otherwise persuaded to accept voluntary sterilization (‘a very slight operation’, after all).

Julian also proposed, in his 1931 book What Dare I Think, that unemployment benefits be made conditional on benefit-recipients having no more children. He wrote: ‘Infringement of this order could probably be met by a short period of segregation, say in a labour camp’.

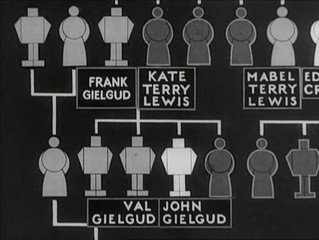

During the 1930s, in fact, he was the most tireless public supporter of eugenics, and was vice-president of the Eugenics Society from 1937–1944. He often spoke in support of eugenics and birth control on the BBC, wrote in support of it for magazines like New Statesman, and defended it in public health broadcasts like the Eugenics Society’s 1937 broadcast ‘Heredity in Man’. In this, he compared the fates of two families — the Gielguds (family friends of the Huxleys), whose family tree is filled with talented people, and a working-class family, whose family tree was apparently filled with morons. ‘It would have been better if they were never born’, Julian says.

Julian presenting Heredity in Man (1937)

If the human species embraced the ‘eugenic phase’ of its evolution, then a glorious destiny beckoned: ‘humanity may increase very rapidly in skill mental power and general vigour…what man can do with wheat and maize may be done with every living species in the world — including his own. It is not ultimately necessary that a multitude of dull and timid people should be born in order that a few bright and active people should be born.’

The Science of Life prophesizes a scientific Rapture (what later transhumanists would call the Singularity), in which humans transcend humanity and become a ‘new race’:

Man has dreamt of prolonging his life; of controlling the destinies of society as he can now control a business or a machine; of eliminating pain; of building a new race, all of whom should be strong and beautiful, clever and brave and good; of harnessing the forces of life to work for him as effectively as he has harnessed the forces of lifeless matter; of creating living matter anew, of getting rid of disease, of making synthetic food and drink and substances which should stimulate and enlarge this or that faculty without being followed by depression or injurious effects, of fashioning new kinds of animal and plants as easily as he fashions clay or wood or metal; of painless quiet and happy dying, of the abolition of fear and worry, cruelty and injustice, of an intensification of the human capacity for living….

Julian has a vision of humans expanding their potentialities, so that mystical experiences become common, and humans perhaps evolve telepathic powers (he was a member of the Society for Psychical Research). Drugs may play a role in this expansion of potential: ‘A time may come when we shall be able to supplement our normal mental powers with chemical assistance’. Julian wrote in 1931:

It should not be impossible to work out a combination of pharmacological substances, each in the right amount and right proportion, which would be capable of toning up a man’s faculties by say ten per cent.

The Science of Life culminates in an ecstatic climax: ‘Great and wonderful and continually expanding experiences lie before life, intensities of feeling and happiness we shall never share, and marvels we shall never see’. The universe itself wills this expansion of human potentialities.

The early transhumanists

In the 1920s and 30s, HG Wells’ scientific utopianism inspired a group of scientists and science-fiction writers, who one could call the British transhumanists (that’s my phrase — Julian himself wouldn’t use the word ‘transhumanist’ until 1951). They included Julian himself; his family friend JBS Haldane, a brilliant scientist who would pioneer of the ‘new synthesis’ of Darwinian evolution and Mendelian genetics together with Julian; JD Bernal, an Irish scientist who developed X-ray crystallography; and the American Herman Muller, who would win the Nobel prize for his work in genetics. They aligned themselves with left-wing politics — Haldane and Bernal were communists, while Wells, Muller and Julian Huxley were socialists with communist sympathies.

Following Wells’ example, these early transhumanists unfurled scientific-utopian visions of the future. In 1924, JBS Haldane published a book called Daedalus, or Science and the Future, which predicted that by the year 2074, the world would be powered by solar and wind energy, humans would eat synthetic foods, and the genetic potential of humanity would be augmented through artificial insemination and ‘ectogenesis’ in vast factories of test-tube babies. Only the intellectual elite would be selected for their sperm and eggs:

The small proportion of men and women who are selected as ancestors for the next generation are so undoubtedly superior to the average that the advance in each generation in any single respect, from the increased out-put of first-class music to the decreased convictions for theft, is very startling. Had it not been for ectogenesis there can be little doubt that civilization would have collapsed within a measurable time owing to the greater fertility of the less desirable members of the population in almost all countries.

Although he would criticize eugenics later in his career, at this stage Haldane seems to support ‘positive eugenics’ — the attempt to improve the quality of the human race by disseminating the DNA of superior families like the Haldanes and Huxleys,

JBS Haldane (left) Aldous Huxley (centre) and writer Lewis Gielgud at Oxford. All three families were part of the British ‘intellectual aristocracy’

One of Julian’s students, the Nobel-prize-winning geneticist Herman Muller, tried to put this into dream into practice. In 1935, Muller published a book, Out of the Night: A Biologist’s Vision of the Future, in which he suggested societies could create ‘genius sperm banks’, where women could choose what superior sperm would create their children. This, Muller believed, could make it possible ‘for the majority of the population to become of the innate quality of such men as Lenin, Newton, Leonardo, Pasteur, Beethoven, Omar Khayyam, Pushkin, Sun Yat-sen, Marx’. Muller actually tried to set up such a ‘genius sperm bank’ in the 30s, and may have asked Julian to donate. Julian occasionally received requests for his A-grade sperm, such as this letter of 1937:

Dear sir, would you consent to being the father of my wife’s child, possibly by artificial insemination. I’m writing this as a feeler and purely from the eugenic point of view.

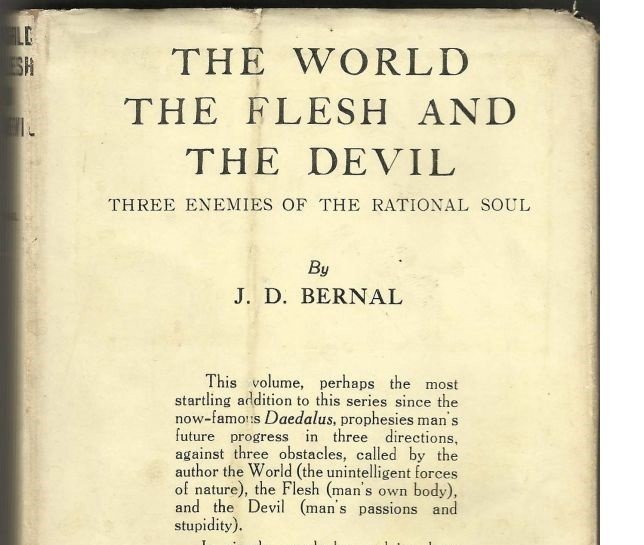

Daedalus was the first in a series of short utopian books called Today and Tomorrow. In 1929, Irish scientist JD Bernal wrote his own contribution to the series, called The World, the Flesh & the Devil. An Enquiry into the Future of the Three Enemies of the Rational Soul. It was even more utopian in its predictions than Daedalus, imagining humans engineering an entirely new species ‘with special potentialities’, through robotics:

Normal man is an evolutionary dead end [wrote Bernal]; mechanical man, apparently a break in organic evolution, is actually more in the true tradition of a further evolution.

JD Bernal

Bernal imagined a future where humans are created in the sort of test-tube factory that Haldane imagined. They then live in their fleshly bodies for around 120 years, before leaving the body whose ‘potentialities he should have sufficiently explored’, and taking on a new immortal robo-body. Humans would be liberated from their egotistic separation by some form of neural-computer link, and become an immortal super-organism.

For Haldane and Bernal, as for Julian Huxley and HG Wells, this is a religious vision of humans become gods through science. Haldane wrote in his diary:

Man has now to look to his own unaided efforts for progress, but he ought to be a god, or something very like it, if he exists 10˄6 years hence.

Bernal wrote:

the individual brain will feel itself part of the whole in a way that completely transcends the devotion of the most fanatical adherent of a religious sect. It is admittedly difficult to imagine this state of affairs effectively. It would be a state of ecstasy in the literal sense…

Brave New World

It was in the context of this ecstatic scientific utopianism that Aldous Huxley wrote Brave New World. The book transports us to London in the year AF (After Ford) 632, or 2540 in our calendar. Britain is no more — it has been absorbed into a World State governed by scientific technocrats. They have taken control of reproduction — all citizens of the World State are test-tube babies born in state-run incubators, just as his friend JBS Haldane imagined.

As in Wells’ Modern Utopia, the population are divided into four castes — Alphas, Betas, Gammas and Epsilons. Their intelligence is genetically altered to fit their place in society, and then all children are programmed to like their position in society through ‘hypnopaedia’ (mantras repeated to them in their sleep) and behavioural conditioning. The Alphas are still educated at Eton, naturally — where Aldous, Julian and JBS Haldane were all scholars.

There is no individual freedom in the World State, but on the other hand ‘everybody’s happy nowadays’. As Wells predicted, there has been a general relaxation of sexual morality — there’s no monogamy, and ‘family’ is a dirty word. Instead, the citizens of the World State practice free love and the occasional orgy. However, the population is carefully controlled through contraceptive devices called ‘Malthusian belts’.

Citizens of the World State are kept happy with a diet of constant distraction — Brave New World is as much a satire on American consumerism as on Wellsian socialism — and are encouraged to shop endlessly. Any time they’re bored, they can listen to jazz or go to the ‘feelies’ (Huxley had particular contempt for movies at this time, little anticipating he’d be working in Hollywood within six years). But the state really relies, for its emotional stability, on a happy drug called soma, which has replaced alcohol:

if ever, by some unlucky chance, anything unpleasant should somehow happen, why, there’s always soma to give you a holiday from the facts.

A poster for a recent TV adaptation of Aldous’ novel

Brave New World has generally been taken as one of the great dystopias of literature, along with books like 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale, and A Clockwork Orange, all of which it helped to inspire. But the fact is, Aldous was far more attracted to his happy dictatorship than he would later admit. In the 1990s, my tutor at Oxford, David Bradshaw, uncovered articles by Aldous from the 1920s and 30s, which revealed the extent to which he shared Wells’ and Julian’s authoritarian and eugenic views.

Aldous shared Wells’ suspicion of parliamentary democracy, which Aldous calls a ‘bedraggled and rather whorish old slut’. He despised the ideal of equality: ‘That all men are equal is a proposition to which, at ordinary times, no sane human being has ever given his assent’. Like most of his Modernist contemporaries, Aldous insisted there is a ‘natural aristocracy’ of Alphas (including the Huxleys, of course), who should be allowed to do what they want.

He believed in the sort of rigid class hierarchy proposed in Brave New World. In a radio broadcast in 1932, Aldous said: ‘in a scientific civilization society must be organized on a caste basis. The rulers and their advisory experts will be a kind of Brahmins controlling, in virtue of a special and mysterious knowledge, vast hordes of the intellectual equivalent of Sudras and Untouchables’. The Alpha class needs protecting while the Deltas and Epsilons should be controlled. In a letter of 1932, he wrote:

About 99.5% of the entire population of the planet are as stupid and philistine . . . as the great masses of the English. The important thing, it seems to me, is not to attack the 99.5%… but to try to see that the 0.5% survives, keeps its quality up to the highest possible level, and, if possible, dominates the rest. The imbecility of the 99.5% is appalling — but after all, what else can you expect?

Unlike his grandfather TH Huxley, who helped to introduce state education, Aldous thought universal education and universal suffrage were terrible ideas — they created a mass of half-educated voters who were easily manipulated by propaganda. The chaos of democracy should be replaced by an authoritarian government run by scientific technocrats with a long-term plan. That ‘deliberate planning’ must include human reproduction. He wrote in 1934:

If conditions remain what they are now, and if the present tendency continues unchecked, we may look forward in a century or two to a time when a quarter of the population of these islands will consist of half-wits. What a curiously squalid and humiliating conclusion to English history!

The minority of ‘super-men’ will be overwhelmed by the mass of ‘sub-men’. He prophesized in 1927 that soon the ‘white races will be at the mercy of the coloured races and the superior whites will be at the mercy of their white inferiors’.

What, he asked, is ‘the remedy for the present deplorable state of affairs?’ It ‘consists, obviously, in encouraging the normal and super-normal members of the population to have larger families and in preventing the subnormal from having any families at all.’ In fact, while Julian only campaigned for ‘voluntary sterilization’, Aldous proposed involuntary sterilization of those deemed unfit. However, he also pondered whether one could really have an entire race of eugenic superbeings. Didn’t someone need to do society’s dirty work? Hence the scientific caste system of Brave New World, where each class is programmed to love their position in society.

What makes Brave New World a good book is its ambiguity. Aldous wasn’t entirely sure what he thought of his World State. It included both ideas he believed in, like eugenics and scientific dictatorship, and aspects of consumer capitalism that he despised. At this stage in his life, he was an ironic sceptic, unable entirely to commit to any one position.

On the whole, however, the book has been read as a dystopia, as a nightmarish indication of the dangers of biological politics and scientific planning run amok. When Leon Kass, the head of president George W. Bush’ bioethics council, argued for a ban on stem-cell research in 2001, he did so with an article called ‘Preventing Brave New World’. Kass told me he’d read Aldous’ book several times and it had a profound effect on his suspicion of grand projects for human enhancement. Still, to this day, criticisms of genetic enhancement inevitably invoke the ‘nightmare’ of Brave New World.

Aldous himself was happy to fall in line with the popular consensus that his book was a dystopia. In 1949, his former pupil at Eton, Eric Blair (George Orwell), sent him a copy of his own dystopia, 1984. Aldous wrote to thank him for the book, and to suggest, politely, that his own vision of the future was more likely — people could be taught to love their enslavement through chemical, sexual and consumer pleasure. He wrote to Orwell:

My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will resemble those which I described in Brave New World.

What he didn’t say was that, unlike his fellow Etonian, he saw himself as a member of this ruling oligarchy. In the 1920s and early 1930s, he saw the human race as naturally and inevitably divided between supermen and submen, oppressors and the oppressed. The question was how to organize autocracy as efficiently and humanely as possible.

He certainly mellowed in his later years, growing less hostile to democracy, and believing more in the possibility of expanding the potential of mass humanity through, for example, psychedelics. But he remained committed to some aspects of Brave New World, such as the idea of a state-wide programme of eugenics. As we’ll see, it features in his last utopian novel, Island, which became something of a hippy bible.

The French novelist Michel Houellebeq was on to something, therefore, when he remarked in his novel Atomised:

everyone says Brave New World is supposed to be a totalitarian nightmare, a vicious indictment of society, but that’s just hypocritical bullshit. Brave New World is our idea of heaven: genetic manipulation, sexual liberation, the war against aging, the leisure society.

In the next chapter, we will examine how environmentalism and nature worship became an important part of spirituality in the United States, and how spiritual ecology merged with eugenics and white supremacy.