‘Can You Pass the Acid Test?’ On Psychedelics and Spiritual Eugenics

I want to discuss the difficult question: to what extent can one cleanly distinguish a ‘spiritual emergency’ from other psychotic experiences.

‘Spiritual emergency’ is a term introduced by two transpersonal psychologists — Stanislav and Christina Grof — in 1989, to describe a disturbing spiritual experience which has some aspects of psychosis, but which should not be treated as ordinary mental illness. Instead, insist the Grofs, a ‘spiritual emergency’, if properly handled, can ‘have tremendous evolutionary and healing potential’.

As Tehseen Noorani has noted, there are issues with this attempt to draw a clean line between ‘spiritual emergency’ and other forms of psychosis.

I want to place this manoeuvre within the history of New Age spirituality and transpersonal psychology, and its troubled relationship with evolutionary theory and eugenics.

The pathologizing of ecstasy

In The Art of Losing Control, I tried to find out how westerners find ‘ecstatic experiences’ today, and to what extent such experiences could be good for one — good in a pragmatist, eudaimonic sense of leading to greater flourishing.

I drew on the history of ecstasy formulated by writers like Aldous Huxley, Etzel Cardenia, Michael Heyd and Bernd Bosel.

As these historians explored, materialist philosophers and scientists have sought, since at least the 17th century, to marginalize and pathologize religious ecstasy, labelling it ‘enthusiasm’, ‘hysteria’, or various forms of psychosis, and describing it as symptomatic of either an over-active imagination, low intelligence, or brain disease.

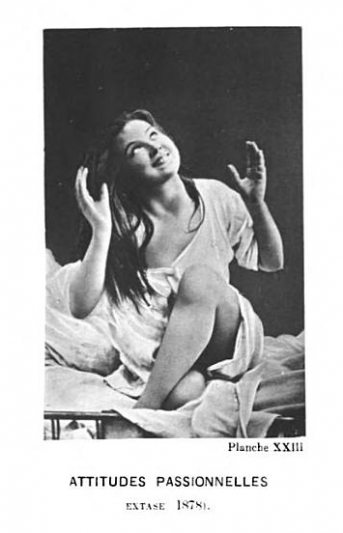

For materialist thinkers like Jean-Martin Charcot and Henry Maudsley, ecstatic or mystical experiences were proof that you’re sick, insane, evolutionarily degenerate, unfit for civilized society, and should possibly be locked up.

A patient of Jean-Martin Charcot’s — he claimed ecstasy was a symptom of a brain disease called hysteria, and took photographs like this to show his patients in mystical poses, to ‘prove’ his point

On the other hand, various counter-cultural movements — ecstatic Christianity, Romanticism, the New Age — defensively declared that ecstatic experiences could be the greatest thing that ever happened to you. They could be proof that you were divinely-inspired, superhuman, elect.

There’s still this unfortunate dichotomy in western culture: either ecstatic experiences are proof you’re degenerate, or they’re proof you’re divinely elect.

Spiritual Darwinism

I want to focus particularly on the attitude to ecstatic experiences found in the New Age occulture in the 1890s, because that’s where the roots of transpersonal psychology lie.

What one sees in the pioneers of New Age spirituality — in everyone from Madame Blavatsky to Vivekananda to Frederic Myers to Sri Aurobindo to Aldous Huxley — is a reaction to the triumph of Darwin’s materialist theory of evolution, and an attempt to incorporate aspects of evolutionary theory into a new spirituality.

This leads to a sort of spiritual Darwinism, to the idea that mankind is spiritually evolving to a higher level of consciousness, and mutating into a glorious new species possessed with hitherto latent potentialities.

Or at least, some humans are.

What one also often finds, in this frame of thinking, is the idea that a select few are having special experiences (cosmic consciousness, peak experiences, samadhi, merging with the Supermind). This select few are the elite, the vanguard of evolution, the Nietzchean supermen, the first strains of a whole new species — homo novus.

This categorization of some well-to-do ecstatics as evolutionarily progressive is a defensive manoeuvre against medical authorities like Henry Maudsley who would deem you primitive and insane if you admit to a spiritual experience.

But it’s a class-bound defensive manoeuvre.

It says, in effect, ‘we couldn’t possibly be primitive or insane — we’re fine, upstanding, successful, respectable members of the upper-class elite. For people like us, ecstatic experiences are actually proof of our evolutionary advancement.’

You see this class-based defence of ecstatic experiences in the papers of the Society for Psychical Research, the Edwardian organisation which in many ways laid the seeds for what would become transpersonal psychology.

It was co-founded in 1882 by Frederic Myers, who declared: ‘the kind of adversary present to my mind is a man like Dr Maudsley…I want…to save the men whose minds associate religion and the mad-house.’

The SPR, in its attempts to prove the legitimacy of spiritual experiences like telepathy or visions of the dead, often highlighted how respectable their witnesses were (‘this ghost-sighting was witnessed by the Duchess of Bedford’ etc). And indeed, it was an extremely well-connected organisation, with not one but two former prime ministers among its members.

Later, in Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley would also use his white, male, upper-middle-class privilege to oppose the labelling of drug-induced ecstasy as pathological or delinquent, and insist instead it was mystical and progressive.

Or at least, it was for people like him.

Supermen and untermenschen

The dark side of this spiritual Darwinism is a tendency to classify other humans, other groups, other races, as backward, degenerate, animalistic, unfit, and requiring control, confinement, sterilization and possibly extinction.

To take one example, we could consider Richard M. Bucke’s book Cosmic Consciousness (1901). It’s a very influential text, arguably foundational for the New Age, for transpersonal psychology, and for psychedelic culture. It’s also an exceedingly strange book.

Bucke argues that a handful of humans — mainly him and his friends — have attained an experience called ‘cosmic consciousness’, which are the first rays of the dawning of a new species. This new species will appear more and more, and eventually run the world and supersede homo sapiens.

While preaching this coming evolutionary shift, Bucke was also a psychiatrist running an asylum in Ontario. He believed insanity was caused by defective sexual organs, and operated on hundreds of women under his care. He also believed some races were incapable of cosmic consciousness and were fated to become extinct.

In many pioneers of the ‘human potential movement’ one finds a similar attitude. ‘People like us’ are the evolutionary elite, the peak experiences, the transcenders, the first buds of homo novus. But we are surrounded by morons, mental defectives languishing at the bottom of the evolutionary scale. These subhumans or untermenschen should be controlled, confined and possibly sterilized, so that elite humanity can evolve to its full potential.

One finds this Nietzschean categorization of humanity into superhumans and subhumans in the ideas of HG Wells, Madame Blavatsky, Annie Besant, Aldous and Julian Huxley, Alexis Carrel, Sri Aurobindo, and many others from the New Age / progressive / psychical research occulture of the 1890s-1930s. And it appears again in the human potential movement of California after the war.

Maslow — a follower of Nietzsche — thought only a handful of humans would get all the way to the top of the pyramid and become ‘self-transcenders’.

Psychedelics and evolutionary spirituality

Now it’s interesting to consider this overlap of the human potential movement and Nietzschean eugenics with regard to psychedelics.

So far, I don’t think there has been much work done on the relationship between the histories of psychedelics and eugenics, but it’s there. To take two examples, Havelock Ellis and Aldous Huxley, two of the first westerners to take and write about mescaline, were both lifelong champions of eugenics.

The post-war culture of psychedelics was shaped by the spiritual Darwinism / evolutionary spirituality of Modernist elitists like Huxley and his friend Gerald Heard.

Psychedelics are seen as the catalyst for the evolutionary advancement of….who? The select few? The young? The beautiful people? Everyone?

For Timothy Leary, LSD was ‘creating a new race of mutants’. This new master-race would, eventually, run the world. For Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, LSD was likewise creating a new race of superheroes, telepathically connected and able to control global events. Terence McKenna and Daniel Pinchbeck also describe psychedelics as evolutionary catalysts for the dawning of a new era, a new level of consciousness, a whole new species.

McKenna’s famous book, Food of the Gods (1992), shares its title from HG Wells’ eugenic sci-fi tale of 1904, in which some humans consume a magic chemical which makes them grow far superior to ordinary humanity. The ‘Children of the Food’ are destined to surpass homo sapiens. A similar story is told in Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End (1953), a favourite text of the Merry Pranksters.

It’s not clear, then, if everyone will make the evolutionary leap, or just a few cosmic mutants. This was — and remains — a lively debate in psychedelic circles. Are psychedelics for everyone? Can everyone handle them?

Within the context of this spiritual Darwinism, it’s interesting to think of psychedelics as ‘the acid test’ — the test of one’s fitness to join the next stage, the evolutionary elite of superheroes.

There have been previous versions of ‘the test’. For Thomas Malthus, it was ‘are you economically productive?’ For Darwin it was ‘have you reproduced?’ For Francis Galton and other meritocrats, it is ‘can you pass the exam?’ For Ernst Junger, it was ‘can you fight with courage?’

For psychedelic Darwinians, it is ‘can you handle a heroic dose?’

Within this frame, it’s obviously pretty brutal if you have a bad trip and freak out. You have failed the acid test. You are not a superhuman after all. In fact, in some ways you’re less than human. You’re on the rubbish dump of evolution.

As a side note, it’s interesting to consider how all these psychedelic leaders somehow ‘failed the test’ — Leary runs from the Buddha in Varanasi, Ken Kesey blows the ‘acid graduation’, Terence McKenna fails to build his alien artefact, Daniel Pinchbeck fails to incarnate as Quetzalcoatl in 2012 and instead pervs on women. These could all be interpreted as variations of Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim, the ultimate story of ‘failing the test’.

Personally speaking, I totally bought into the mythology of the Merry Pranksters when I was a teenage raver. I also thought of myself as ‘young, immune’…a superhero! So when I had a bad LSD trip aged 18, and felt shattered for months afterwards, I took it as a colossal failure, a proof of my unfitness, even my unworthiness to exist.

So one can see how these sorts of rigid either / or classifications of ecstatic experience can play out in harsh and dehumanizing ways.

Are all psychotic experiences potentially ‘spiritual emergencies’?

Let’s return, finally, to the Grofs’ concept of ‘spiritual emergency’.

In some ways, the concept was a very helpful advance from the unfortunately rigid classification of ecstasy as either pathological and totally bad, or divinely inspired and totally good.

It recognized a middle-ground, admitting that ecstatic experiences can be both beautiful and terrifying, both meaningful and bewildering, both empowering and traumatizing, both connecting and alienating.

However, as Noorani points out, there is still the sort of defensive manoeuvre we saw at earlier stages in the history of transpersonal psychology.

The Grofs insist, to paraphrase, these experiences — spiritual emergencies — are part of elite humanity’s evolutionary transition to a higher level of consciousness.

Those experiences — common-garden psychotic experiences — are merely mental illness, probably organic or physiological in nature, and indicative of evolutionary regression.

These experiences happen to people like us, people engaged in advanced spiritual practice, Esalen people, self-transcenders. Rich, educated, white people. The elite.

Those experiences happen to other people, at the bottom of the pyramid, ‘mass man’.

What my co-editor Tim Read and I found, when we gathered together accounts of ‘spiritual emergencies’ for the book Breaking Open: Finding a Way through Spiritual Emergency, was that it was not in practice very easy to draw a clean line between spiritual emergency and psychosis.

Some of our contributors had temporary psychotic experiences after taking psychedelics or after intense spiritual practice. Some crises were triggered by a bereavement, personal crisis, or even a political crisis.

Sometimes it was a one-off experience, sometimes it happened more often.

Sometimes it was subsequently interpreted entirely positively by the experiencer, sometimes it was interpreted more ambiguously.

What these experiences had in common, what makes the label ‘spiritual emergency’ somewhat useful, is that the people who had the experience felt there was something meaningful in it. They felt the experience was both awe-inspiring and also terrifying. The experiences felt ecstatic, even mystical. They didn’t feel simply delusional and pathological.

Almost all our contributors also found certain self-care and mutual aid practices helpful, such as finding a calm, supportive and safe environment; grounding themselves in the body and in material reality; finding sympathetic people to connect to; and seeing their experience through a frame of kindness, patience and potential growth, rather than a frame of breakdown and disease.

For all of our contributors, their crises did not mark the start of a long slide into worse mental functioning.

What caused these crises? We simply don’t know. We don’t know to what extent the causes were genetic, physiological, chemical, cognitive, social, economic or spiritual. But it’s likely to be a combination of all these levels. It doesn’t have to be either physiological or developmental or cognitive-spiritual.

Nor do treatments have to be either cognitive-spiritual or chemical. Some of our contributors find medication helpful, others don’t.

As Mike Jackson and Charles Heriot-Maitland have noted, it’s difficult to draw a clean line between mysticism and psychosis — experiences of ego dissolution exist on a continuum, depending on how much insight and skilful means a person has to navigate the experience, and also depending on how supportive their cultural and socio-economic context is.

In conclusion, the term ‘spiritual emergency’ was helpful in marking out a middle-ground between ‘psychosis’ and ‘spiritual experience’. But transpersonal psychologists tried too hard to bracket off this type of experience from common-garden psychosis rather than admitting a continuum. As a result, the term itself has not had much influence, even within New Age and psychedelic circles.

Can we not extend the same respect and dignity to psychosis in general as we do to spiritual emergencies?

In other words, can we recognize that for some people, psychotic experiences are not simply breakdowns or symptoms of disease, but also sometimes beautiful, meaningful, and even spiritual experiences?

Can we recognize that labels are sometimes helpful, but they are also crude and historically contingent classifications of mental states that are dynamic and hard to pin down?

Mental experiences in general, and ecstatic experiences in particular, are ambiguous. They are not well-approached with rigid either / or classifications. They are not easy to pin on a map, to say ‘this was nothing but a brain pathology’ or ‘this was definitely a shamanic initiation’ or ‘this was definitely the cave descent on the hero’s journey’ or ‘this was definitely a spiritual emergency on the path to an evolutionary shift’.

Our maps are crude, not to be confused with the territory itself. Instead of fixating on labels or causes, we can shift our focus to ‘what helps now?’

Mental states and indeed all experiences are not essentially ‘good’ or bad’. It depends on the view you take of them. That’s as true of cancer as it is of psychosis.

As Noorani has suggested, we need to consider our classification of psychosis as the terrifying Other of our rational civilization.

Altered states of consciousness are something that happens to lots of people. They’re neither totally bad nor totally good. Neither proof of our unfitness, nor proof of our divine election.

It depends on how we relate to them.

I hope we can learn to support people to come to terms with their experiences, to make friends with them, and to find ways to integrate them, including self-care, mutual aid, economic support, and if it’s helpful medication.

‘Coming to terms’ means finding the frame, the view, and the terminology that you find liberating. ‘Spiritual emergency’ is one such term, not perfect, but sometimes useful.

Here’s an Aeon article I recently wrote on this topic. Here’s some videos by contributors to Breaking Open.