Dan Ariely and behavioural economics

I'm writing a piece for the Wall Street Journal on behavioural economics, which is a relatively new field of economics that tries to incorporate the psychology of irrational human decision-making into its theories. It's become very hip in the last few years - one of its practitioners, Daniel Kahneman, won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2002 - and particularly faddish since the Credit Crunch cruelly exposed our capacity for irrational market behaviour.

I'm writing a piece for the Wall Street Journal on behavioural economics, which is a relatively new field of economics that tries to incorporate the psychology of irrational human decision-making into its theories. It's become very hip in the last few years - one of its practitioners, Daniel Kahneman, won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2002 - and particularly faddish since the Credit Crunch cruelly exposed our capacity for irrational market behaviour.

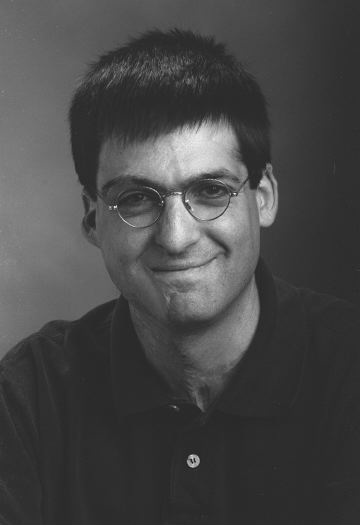

I recently interviewed one of its leading thinkers, Duke University economist Dan Ariely, who wrote a successful book in 2008 called Predictably Irrational, and who's just brought out a sequel, called The Upside of Irrationality.

For once, my economics journalism is meeting up with my psychology journalism, so I thought readers of this blog might enjoy reading the interview:

JE: The main idea in behavioural economics seems to me that humans have certain 'cognitive biases' which lead them to make irrational choices in life, including economic choices. Can you tell me some of them that investors should be particularly wary of?

DA: There are quite a lot of them. The question is which come into play in which environments. The easiest with regard to investing is becoming aware of how our emotions affect our decision-making.

How do emotions work on us? They come from the outside. We react to an external stimulus, this sets off a reaction inside us, and once it starts, it's very difficult to switch off. So some very simple advice for investors is to try to make decisions without the influence of emotions.

For example, imagine two different ways of investing. One is open your computer, open up your online brokerage account, see how your portfolio is doing, and then make a decision to buy or sell stocks. That is a very emotional way of investing, because you will have an emotional reaction to the day-to-day performance of your stock and will make a decision based on your emotions.

Instead, you could first think about your stock strategy, reason about it, read, think, contemplate, and then, only occasionally, look at how the stock is doing.

JE: So check your portfolio performance less often?

DA: Yes. And be aware of your emotional state when you do so, and try not to make instantaneous decisions in the heat of the moment.

Another cognitive bias to be wary of is 'anchoring', also known as disproportional affect. People get very attached to the price at which they originally bought something, and will hold on to a stock for too long, when they should have already sold it, because they want to see it rise above the original price they bought it. Because realising a loss is very painful.

So they don't ask themselves 'will this stock go up or down in the future?' but 'will it go up and down relative to the original price I paid?' And many trading websites exacerbate this by showing the original price you paid for a stock. This can lead you to make decisions not in your best interests.

JE: It sounds like you don't think much of 'gut instinct', or the idea of the wisdom of following our instinctive reactions.

DA: No, I don't. You need to educate your gut instinct, train it, and subject it to constant feedback. Let's say you are kicking a soccer ball on a field, and when you kick it, you close your eyes and guess where it will land. If you do that 100 times, your gut instinct might tell you quite accurately where it will land.

But investing in the stock market is much more complicated than that. The link between cause and effect is much harder to follow, and the level of feedback is much more complex, and noisier.

JE: You say that the great 'hope' of behavioural economics is that it can, or has, discovered the typical cognitive biases that humans are susceptible to. And by telling people about these cognitive biases, behavioural economics can make us less irrational, and more rational. But is there any evidence that people can actually train themselves to be more rational?

DA: Yes. For example, we're teaching people to stop paying a very high amount for their portfolio managers, because a lot of them are just index trackers.

JE: OK...Now it seems to me that when behavioural economics is talking about teaching people to become more rational and less emotional, they're really talking about therapy or self-help. Is that what behavioural economics is getting into? For example, training people to be more aware of their thinking processes and emotional reactions through, for example, meditation?

DA: Not really. We're thinking about very simple mechanisms. For example, when you go into a restaurant, and you tell the waiter you're on a diet, and the waiter offers you creme brulee, you'll choose it, and meditation won't help you. Maybe the Dalai Lama can resist the creme brulee, but most of us can't. So let's create a situation where the waiter doesn't offer you the creme brulee. Let's find a different way to present the choices, or a different way to process it.

JE: You're talking about two different things: firstly, changing how a company presents its consumer choices; and secondly, changing how we process those choices. On the first point, how do you change how a company presents its consumer choices? Through government regulation? Because presumably it's in a company's interests to get a buyer to manipulate these cognitive biases so people spend as much as possible.

DA: Not always. An investment house could try to 'nudge' investors towards better and more rational decisions. And on the second point, how an individual processes the consumer choices, you might ask yourself, do I really want to go into this situation in this emotional state?

JE: Let's say I do train myself to be more dispassionate and rational in my investing. If the rest of the market is still just as irrational in its decision-making, does investing 'rationally' become less about assessing the actual worth of a company, and more about accurately predicting the craziness of other people?

DA: Some of it is like that. If people are running away from a market because they're panicking, you can make a dispassionate decision that they have missed the real value of a stock. A lot of hedge funds do that - their strategy comes from taking advantage of market 'inefficiencies', which often mean when people have been led by their emotions to make a false assessment of something's value.

If everyone was perfectly rational in their market decisions, and prices perfectly reflected the value of an asset, there would be hardly any trades. Trades come because of asymmetries in information, and because you think you're more rational than the others.

[This, by the way, raises a question in my mind: economics assumes that things have a 'value', and you can discover this 'true value' through scientific analysis of supply and demand etc. But that seems like nonsense to me, because how can science ever analyse whether something is really or value, or should be of value, or not? How can it tell us what gold is 'really' worth? Maybe it's really worth nothing and it's only the foolishness of humans that thinks it is. By 'fundamental value' what it really means is the consensus of the irrational mob, and that consensus is never stable.]

JE: It seems like one of the mistakes made by classical economics, and one of the mistakes made during the Credit Crunch, was economists became over-confident about their ability to predict and control events. Is there a danger that behavioural economics will become the new consensus, and economists will fall prey to the same over-confidence, by believing that it can somehow accurately 'predict' our irrationality?

DA: The difference between classical economics and behavioural economics is that the over-confidence is not symmetrical. I don't think behavioural economics will replace classical economics. Nobody does. Classical economics captures some of human behaviour, but not everything. Behavioural economics points out that some aspects of human behaviour are missing, and they try to supplement classical economics with that missing component.

So standard economics says we can describe reality 100% accurately. We say, this model doesn't include everything.

JE: And the hope is that, through providing this supplement, economics will become more accurate, and better able to predict and control events?

DA: Yes.

JE: But isn't that falling into the same trap of over-confidence in social scientists' predictive expertise?

DA: We're empirical. The standard economic approach is almost a religious, faith-based approach. We're happy to do experiments. Because we deal with data, our claims are not 100% certain, but we can get closer to accuracy.

JE: But arguably that is simply putting a lot of faith in experiments, and their applicability to the messiness of the outside world. Some behavioural economists, like John List, have shown that some experiments that work one way in a laboratory environment work very differently in a field environment where people aren't aware they're in experiments.

DA: Sure, but John List is not against experiments per se. He's just saying you need to run both lab experiments and field experiments. It's like medicine - you start off in the lab working on rats, then you try things out in the field, then finally, when you're reasonably confident, you might introduce it through policy.

JE: Finally, I want to talk about the work of Daniel Kahneman, and his studies of happiness, what makes people happy, and how this should influence public policy. What do you think of his work?

DA: I think that field, of measuring and studying happiness, has learnt some really important things, and some stuff we don't yet understand. I think it's a little early to introduce the ideas as public policy. That's a little premature, but it could eventually help.

JE: But do you think economics, as a social science, can ever tell us what we should choose to do in life? Isn't that a question for moral philosophy?

DA: Well, economics could tell us that people who spend their entire lives working to be rich and happy might end up rich but not necessarily happy.

JE: But can happiness levels really be measured scientifically, without getting into philosophical questions of what happiness is, of whether some forms of happiness are higher than others?

DA: So you have a problem with the idea of measuring reported satisfaction levels. But what if we showed that, for example, some life choices led to higher levels of depression, or to a greater incidence or heart attacks. Would you have a problem with using public policy to change that?

[I didn't answer...but you could say that is a question of the moral education of the individual, of trying to teach them what should be valued in life, and that it's difficult if not impossible to 'prove' that certain life choices lead to depression, or to make the moral argument that just because a life choice leads to depression, we should definitely not choose it.

The highest levels of suicide are among doctors and artists, but does that mean no one should become a doctor or an artist? Some life choices involve more stress and suffering. That doesn't mean no one should choose them.

I also wasn't entirely convinced that simply telling people what cognitive biases to look out for will necessarily make them less likely to fall into them. The sort of mental training you need, it seems to me, is more intense, and will very probably end up in mindfulness and relaxation exercises like those found in Buddhism; or in cognitive self-scrutiny exercises like those found in Stoicism or CBT.

And, finally, it does seem to me that behavioural economics could easily fall into the same fallacy of expertise that standard economics fell into - the fallacy that social scientists can accurately predict the messy chaos of human behaviour. I tend to side more with Nicholas Nassim Taleb, another economist who has the courage to say simply 'we know a lot less than we think we do, so be humbler about your powers of prediction, and accept that reality is going to constantly confound your theoretical models.]