Instead of pills, social connection

I’ve been considering the mental health impacts pf the COVID pandemic, and wondering how governments and organisations can support people’s mental health in the difficult months and years ahead.

One big lesson from the lockdown is that when emergencies hit and the state wobbles, people often find ways to cope. Self-help and mutual aid have flourished in the last three months. People have found solace in baking, cycling, pets, gardening, online courses, prayer, Tik-Tok dancing and volunteering.

Many say they actually feel more connection to their community in lockdown. Most say they don’t want life to go back to normal — not in all ways anyway.

I am keen to learn from this and encourage this sort of approach to suffering and flourishing — ie a non-medicalized, whole-person, strengths-based approach that recognizes the variety of ways people can cope with adversity, individually and communally.

But here’s the question I’ve been pondering. How can we support that sort of approach in a period when mental health service referrals could rise by 30% (according to one mental health trust), while mental health services budgets are frozen, local government budgets are stretched, unemployment is soaring, and the voluntary sector is also badly hit — one in ten charities could go bust in the next year, 400,000 workers in the arts sector could be made unemployed, and the physical infrastructure of community has been devastated by the virus.

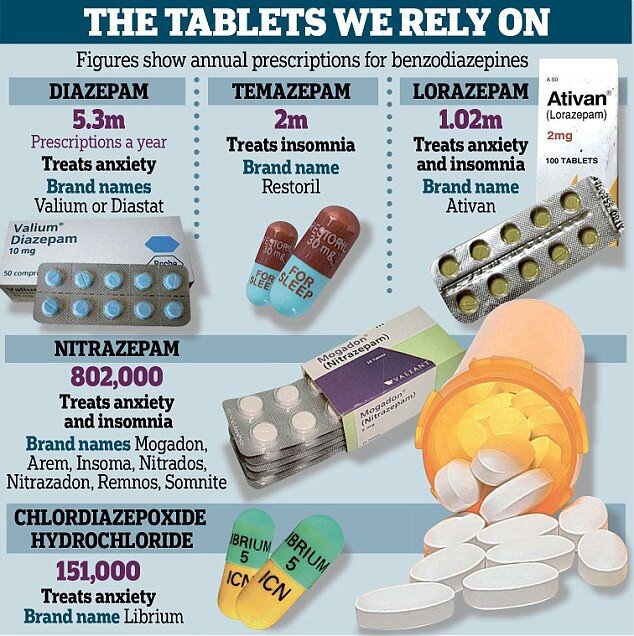

It’s a very difficult situation. And there’s a real risk the solution societies will reach for is simply ‘more pills’. In the UK, one in seven adults are already on anti-depressants. Even more dependence on mood-altering pills is not a good solution, not least because of the proven risk of addiction (the NHS admits one in four people in England are prescribed addictive drugs) and negative side-effects including opiate overdoses and anti-depressant-triggered suicide.

Instead of pills, social connection

A whole raft of policy initiatives is needed, from apprenticeships to a Green New Deal. I very much hope legalization of drugs is one part of that radical response — please, take all those billions out of the hands of gangs and prison-operators and give it to the Treasury to spend on education and health.

Another approach which shows promise is social prescribing. This week, I interviewed the CEO of a new organisation called the National Academy of Social Prescribing, James Sanderson.

The idea of social prescribing is simple. Roughly 20% of people who go to GPs have what Sanderson calls a ‘non-medical need’ — they’re feeling sad, lonely and disconnected. ‘Medicalizing that is the wrong answer’, Sanderson says. ‘Instead, social prescribing tries to connect them to community groups.’

He says:

Some GPs have always done that, they’ve always had a drawer full of leaflets from local groups. The most famous example is Sam Everington, a GP who set up the Bromley-by-Bow social prescribing practice in the 1980s. But so far, it’s been confined to a handful of forward-thinking individuals operating at the margins of bio-medical medicine. The biomedical approach has preferred drugs and surgical interventions. That’s fine, drugs are still good. But there’s increasingly a realization that the biomedical approach is limited. If someone has arthritic hips, you can keep giving them injections of cortisone, but you may get as good or better outcomes by encouraging them to go swimming.

In the last couple of years, interest has grown in social prescribing. Sanderson points to a movement called ‘Rethinking Medicine’, run by Alf Collins, head of personalized care at the NHS.

And there’s also a growing evidence base for social prescribing, produced by clinical psychologists like Daisy Fancourt — she tells me a paper she produced for the World Health Organisation (with Saoirse Finn) on the health benefits of the arts has been downloaded over 400,000 times.

As of this year, there’s a new NHS strategy based around ‘universal personalized care’, which Sanderson was spear-heading before he moved to the Academy. It aims to ‘increase people’s skills, knowledge and confidence to live independently’, he says.

Social prescribing is a central part of this new personalized strategy. Sanderson says: ‘We’re embedding social prescribing in primary care. We have a budget of £500 million, which we will use to employ 4000 ‘link workers’, who will connect people to local community groups.’

He says there is already a mature ecosystem of social prescribing in some parts of the country — Rotherham, Frome, Croydon — and the NHS now wants to ‘industrialize’ social prescribing (which sounds rather ominous).

I am all for encouraging people’s existing cultural responses to adversity, rather than saying ‘this is a medical problem which requires a medical solution’. As Ivan Illich pointed out, that approach is iatrogenic — it actually disempowers people, undermines their natural and cultural coping mechanisms, and creates a bottle neck for state assistance.

But I wonder if social prescribing is still a rather medicalized approach to social disconnection. After all, it’s still funnelling people through GPs, still using the language of ‘prescriptions’. Is it really the NHS’ job to try and heal loneliness and everyday suffering? Isn’t supporting community organisations the job of all of the government, and all the rest of us?

Sanderson says:

In an ideal world, you wouldn’t have lonely and isolated people accessing NHS, they’d naturally find community. But the fact is, the main place they go is the NHS. It’s a trusted brand, the anchor in communities. But it’s important we have a two-pronged approach. First, we’re embedding social prescribing in primary care. Secondly, the National Academy is working to find local organisations and help them grow.

That, I guess, is why the government set up the ‘National Academy’ at arm’s length from the NHS, and based it in the South Bank (a place close to my heart for social prescribing — I attended a mental health support group there when I was 23).

The Academy will also appoint ‘regional coordinators’, who will act sort of like coaches for local voluntary organisations: ‘They will identify the organisations, connect with them, and consult with them on best practice and how to get funding’.

That’s an important part of the jigsaw, because otherwise there is a risk that social prescribing is a way for the NHS and the state to palm off vulnerable people to voluntary organisations without paying them.

This week, for example, I spoke to a colleague of mine at my university, Sarah Chaney, who has volunteered in a neighbourhood mutual aid group over the last three months. She tells me the group has received referrals from local mental health trusts, so she’s been on the phone helping vulnerable people just discharged from psychiatric hospitals, and doing this unpaid. Her colleague in the mutual aid group, Mahnaz Bati, says the local council hasn’t given them any assistance at all.

Sanderson says:

There’s a need to look at ways to make funding more effective. There are lots of things that are free, for example Park Run. But that’s not necessarily enough. What if the person can’t afford trainers, or child care? What works well tends to be a blend of sources. For example, there’s a great organisation in West Ham which supports men with mild to moderate mental health needs. Its supported by an NHS Clinical Commissioning Group (CCGs), and West Ham FC, and Sainsbury’s.

I hear from some sources that social prescribing organisations don’t get any money from the NHS, but Sanderson says ‘a lot of funding from CCGs and local government goes into organisations — Rotherham has an £800,000 fund for example. But some voluntary organisations are wary of accepting statutory funding and becoming statutory organisations themselves, because it would make them inflexible.’

Sanderson suggests that being an approved NHS social prescribing partner may make it easier for small local organisations to attract funding from local businesses (they may only need small grants in the thousands or tens of thousands). He says: ‘A lot of people are reluctant to fund voluntary organisations because they don’t know where they fit in. If they’re an NHS partner, they’re immediately more credible.’

In some ways, the pandemic has underlined the argument for social prescribing. But in other ways, it’s made the model much harder — with community infrastructure shut down and voluntary and arts organisations facing bankruptcy. Sanderson says: ‘It is a very challenging time for sure. But this initiative could be a way to support recovery.’ But organisations desperate for a lifeline will have to wait, unfortunately. The Academy only set up in March, is still hiring staff, and hopes to launch its regional coordination in September.

What kind of organisations could be eligible? There are four quadrants, Sanderson says: arts and culture, sports and exercise, the natural environment, and education. What about faith groups, I ask. Might some GPs be reluctant to prescribe that, because of their own cultural bias against religious and spiritual groups?

Sanderson says: ‘The link workers will speak to people about what matters to them. If faith is important, that linkage can happen. Faith-based organisations have really embraced this.’

And how about adult education organisations and universities? ‘Yes, we’re keen to work with organisations like the University of the Third Age. Classes in libraries don’t just offer learning, but also community. We’re also launching an academic partner-programme.’ I personally am very keen to encourage universities to rediscover their community role, and will write more on this next week.

Finally, what about those groups who may suffer from emotional problems, but who typically avoid GPs, such as men? ‘It’s true there are certain groups who do not typically access mainstream services. We need to look at ways to reach those groups. Last week, for example, I met with the Premier League to partner with them on the Game Changing programme, and I’m also meeting with the English Football League Trust.’

We may also be able to learn from other countries. Although Sanderson says this is the first ever government programme to support psycho-social initiatives, in many ways ‘social prescribing’ is what developing countries naturally do, in the absence of western-style mental health services or drugs.

We can learn from community-led mental health responses in countries like India and Zimbabwe (like the ‘friendship’ bench, below). And we should also be wary of simply exporting our drug-led response to emotional problems — particularly when pharmaceutical companies are relying on new developing country markets to boost their sales of anti-depressant drugs.