Mad Men and the impossibility of transcending capitalism

The documentary maker Adam Curtis wrote in 2010: ‘In Mad Men we watch a group of people who live in a prosperous society that offers happiness and order like never before in history and yet are full of anxiety and unease. They feel there is something more, something beyond. And they feel stuck.’

The system in which the characters are stuck forces them to live divided lives in divided selves. Don Draper, in particular, has learned to put on a mask in order to get ahead and leave behind his background of shame and poverty. But the cost of this pact with American capitalism — I will put on a mask if you let me become successful — is a gnawing loneliness and restlessness. In the first scene of the sixth series, we see him on a beach, next to his beautiful wife, reading in the sun. He’s reading Dante’s Inferno:

Midway through the journey of our life

I found myself within a dark forest,

For the straight path had been lost.

Of course, Dante gets out of the Inferno. How about Don? Is there any transcendence? Any redemption? Any escape from the system? This is one of the great questions which shows during TV’s Golden Age has asked us — from The Wire (no escape), to The Sopranos (no escape), to Six Feet Under and Twin Peaks (some escape maybe), to Breaking Bad (definitely no escape).

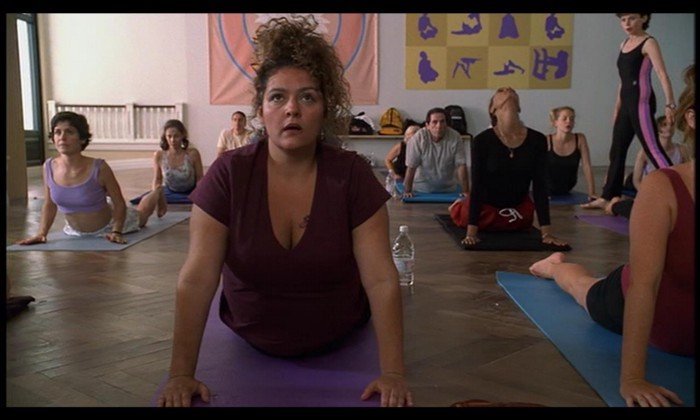

Matthew Weiner, creator of Mad Men, used to write for The Sopranos, and both these shows excel at exploring some of the ways people try and escape from late capitalism through therapy or New Age spirituality, and yet somehow remain stuck in the system, just as confused and egotistical as ever.

Janice Soprano seeking escape through yoga

In fact, as Mad Men explored, late capitalism rapidly co-opted the insights of therapy, sexual liberation, the arts and New Age spirituality, and used them to sell us things (this is the main point of Adam Curtis’ documentary, Century of the Self, which aired three years before Mad Men began).

So, on the one hand, Don Draper has a sharp artistic insight into the human condition. Some of the key moments of the show are moments during a high-stakes pitch, where he seems to have run out of ideas, and then suddenly he has a brilliant epiphany, and everyone is wowed by his creative power. He’s a Michelangelo of Madison Avenue.

And yet what are these epiphanies? Revelations from God? Glimpses of a better world? No, they’re catchphrases to sell cars or cigarettes. That’s what the idea of epiphany has been reduced to in late capitalism: the magical creation of a new product or ad slogan. That’s what all those innovation companies and creativity gurus are selling: more imaginative ways to sell us things.

Don has a deep sense of the anguish, dissatisfaction and craving inherent in the capitalist society (and perhaps in the human condition). Indeed, he capitalizes on it. One of my favourite moments in the show is when Don pitches to Dow Chemicals. ‘We’re happy with our agency’ says the man from Dow. ‘Are you?’ Don responds.

You’re happy with 50%? You’re on top and you don’t have enough. You’re happy because you’re successful, for now. But what is happiness? It’s a moment before you need more happiness. I won’t settle for 50% of anything. I want 100%. You’re happy with your agency? You’re not happy with anything. You don’t want most of it, you want all of it, and I won’t stop until you get all of it.

It’s a brilliant encapsulation of the drive, the desire, the libido, the Id, at the heart of capitalism (or perhaps at the heart of the human condition). The yearning for more, more, more. The sense that life will be better when you get there, to the next peak, the next triumph. And then? ‘What is happiness? It’s a moment before you need more happiness.’

The Buddha called this dukka, craving, that restless inability of the mind to have enough, to be enough. The ego-mind leads us on the longest shaggy dog story in cosmic history, promising us that we will finally be happy if we just follow its commands and achieve this next achievement, or make this life change, or buy this product. But we will never be happy, the Buddha said, until we awaken from this illusion, and realize that the moment we satisfy our ego-desires we are not satisfied and yearn for something else. Yet we keep falling for the lie!

Don gets this. And he sells it. He sells the promise that you will finally be happy when you get his product.

So is there no escape from this wheel of desire and suffering?

Certainly, various characters seek various forms of escape. The most common form of escape is booze. The show is swimming in it, the male characters keep their pain and frustration sedated with the bottle.

Others seek more radical forms of escape as the Sixties counterculture gains momentum: Paul the copy-writer joins the Hari Krishnas, though it seems pretty phony. Roger Sterling’s daughter joins a hippy commune, again it seems phonier than the capitalism it rejects. Roger himself spends a few seasons experimenting with LSD and group sex — it doesn’t really make him any less selfish, though he is perhaps the most likable and content character in the show. Don also finds an escape of sorts through his constant affairs and one slightly weird S&M dalliance. Ken Cosgrove has the option of escape into bohemian creativity by becoming a novelist, though he doesn’t take it. Ginsberg the eccentric copy-writer takes the escape of psychosis. And Lane Pryce takes the escape of suicide.

Don, meanwhile, often takes the escape of going on the road. That old American dream: let’s get lost. Let’s disappear. But this is not a long-term solution. By the final episode, after months of traveling, he feels truly lost, and washes up in a New Age retreat on the coast of California.

This retreat is clearly based on Esalen, which was the spiritual centre of the Human Potential Movement in the 1960s, the place where unhappy middle-class people came to learn yoga, give each other massages, and seek through endless workshops and encounter sessions for ‘the real me’, the pure me, the me stripped of all baggage.

As Curtis explored, the Human Potential Movement rapidly became absorbed by late capitalism. Today, there is a booming industry of business coaches who use the ideas and techniques of Human Potential in companies and weekend courses, to help people find their authentic selves within late capitalism. The system proved flexible enough to absorb all the radical experiments of the 60s counter-culture, and turn them into commodified experiences.

We see the apparent impossibility of genuine transcendence in the show’s final scene. Don is meditating and chanting ‘om’ — a very unlikely scene. Eyes closed, a quiet smile curls upon his face. A bell chimes. Has he finally found the answer? Has he unlocked the mystery of his self? The scene cuts, and its a famous 70s advert for Coca Cola, ‘I’d like to teach the world to sing’. The implication is that Don’s epiphany at Esalen is merely another idea for an advert, another way to sell things. (Perhaps the ‘merely’ here is mine rather than Weiner’s — he says he thinks the Coke advert is genuinely beautiful).

This might make Mad Men sound a very dark and cynical show, and it certainly has its dark edges. But for some reason it’s not a dark show. I think that’s because the characters and stories are drawn with such love, such deft words and gestures. None of them are all bad or all good. We care about them, want them to be OK, are interested in their progress. The writers respect our intelligence, and know they can tell a story through a word, a look or a gesture, and we’ll pick up a subtle reference to something earlier in the show. A point doesn’t have to be obvious: ‘subtext is pleasure’, Weiner says. Characters’ motivations are both revealed, and also mysterious — as in the Sopranos, motivation is never a simple cause-effect equation.

And, unlike every other Golden Age hit, this is a show where no one gets murdered. Think of the body-count in the Sopranos, The Wire, The Shield, Deadwood, Twin Peaks, Breaking Bad, The Walking Dead. Mad Men instead captures our attention with what Weiner calls ‘the quotidian’, with the details of office and domestic life in the maelstrom of the 60s. Office life can feel stale, flat, dull, but it never feels boring at Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce (particularly when half the office is on amphetamines).

There’s a tremendous fondness for office life in Mad Men— the friendships, the personalities, the drama, the triumphs and failures, the flirting and romance, the collective mission, the kookiness. In the most critically-acclaimed episode — The Suitcase, in season 4 — Peggy prefers to stay in the office working with Don rather than go see her boyfriend and family. This is 64 hours of TV largely set in an office, and it is gripping. Maybe, with COVID, we’ve passed the golden age of office life — Mad Men makes me miss it.

Even if there is no great transcendence from the system, we do see better life-opportunities open up for female and black characters as the civil rights movement progresses. Compare the autonomy and power of Joan and Peggy at the end of the show with the simpering bimbos they were at its beginning.

So, in the words of the Peggy Lee song that begins the final season, ‘Is that all there is?’ The show seems to agree with Sigmund Freud — the only transcendence we can hope for are the consolations of work and love.