My top ten tramps in literature and culture

I was watching Rev the other day. It’s a sitcom about a beleaguered inner-city priest, played by Tom Hollander. This series, Rev has been facing all kinds of trials. In the Easter episode, things get really bad. Adam’s reputation is rock-bottom, his church is facing closure, and he finds himself on a hill overlooking London, where he meets God in the form of a tramp, played by Liam Neeson. It’s a lovely moment (sorry for the crap picture quality):

As it happens, I’ve always been interested in the idea / symbol / archetype of the tramp as a messenger from the spirit-world. This interest (or, if you prefer, obsession) started when I was 19 and suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. I had a series of nightmares about a tramp. In my dreams, the tramp went from being a mortal enemy, to being someone I had to rescue, and someone who in turn could heal me. I've never had dreams that have felt so significant before or since.

Jung suggests that the wounded or dissociated parts of our psyche - what he called the Shadow - can appear to us in our dreams in the form of a tramp. They represent the refuse of our psyche - the bits we have refused to acknowledge because they seem shameful, barbaric or uncouth. The Shadow is frightening to us because it’s a threat to our Personae, to the masks of civility we present to others. But if we have the courage to face the Shadow, and to recognize it as a part of us, then it can bring us healing, wholeness, and grace.

This archetype of the Holy Tramp - a marginal figure who somehow redeems individuals or even whole civilizations when they have become caught up in image and status - comes up again and again in myth, religion and culture. Just as the Shadow appears in our dreams when we have become cut off from our deeper self, so it seems to appear to artist-prophets, who then present their society with its Shadow to remind them of the spirit-world they are losing contact with.

Here, in a Buzzfeed sort of way, are my top ten sacred tramps from western literature. This is a fairly idiosyncratic list, and I apologise now for leaving Huckleberry Finn off it!

1) Oedipus

In Oedipus at Colonus, Sophocles presented his Athenian audience with a nightmare figure - Oedipus the tramp, thrown out from the city of Thebes for killing his father and marrying his mother (without realizing they were his parents). He has no home, no possessions, no friends, no citizenship. He is a sort of shadow of his former self. He represents the worst-case scenario for his audience - total ostracism.

And yet Sophocles suggests that Oedipus has something his audience has lost. Oedipus has endured the wrath of the Gods out in the wilderness, and as a result he has gained a sort of inner power, or charisma. This charisma brings blessings to whoever has the strength to see through his loathsome exterior to the divine power within. At the end of the play, Oedipus strips off the rags that he wears, and is transformed into a God. It’s a beautiful moment of quasi-Christian redemption, quite rare in ancient tragedy.

2) Eros / Cupid

In Plato’s Symposium, Socrates describes Eros as ‘a daemon’, intermediate between the gods and men, conveying to the gods the prayers of humans, and conveying to humans the ‘commands and rewards of the gods’. Daemons or messengers appear to humans, Socrates says, through prophecy and dreams. And Eros, contrary to popular art, actually looks like a tramp.

Plato writes: ‘he is always poor, and anything but tender and fair, as the many imagine him; and he is hard-featured and squalid, and has no shoes, nor a house to dwell in; on the bare earth exposed he lies under the open heaven, in the streets or at the doors of houses, taking his rest.’

Eros, then, is the soul in exile, battered and bruised, dressed in rags - to all accounts loathsome. But actually, beneath the unpromising exterior, he is an immortal messenger, for those with the wisdom to recognize it. This relates to Socrates - also ugly on the outside but with amazing spiritual treasures on the inside. It also taps into a tradition in Greek religion that Zeus sometimes appears as a tramp or outsider (Zeus Xenos) to test how kind people are to the marginal or outsiders. To those who welcome the tramp in, great blessings are given. To those who drive the tramp out come curses.

The myth of Cupid and Psyche, by the by, which first appears in Apuleius' Golden Ass, can be read as a Platonic allegory of the divided psyche's attempt to unite and heal itself. Psyche is betrothed to a loathsome monster who turns out actually to be a gorgeous demi-god. It inspired the fairy tale Beauty and the Beast, also about a daemonic monster transformed by love and sacrifice, and perhaps inspired many other stories of 'monsters transformed by love / endurance / atonement' - such as Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away.

3) Diogenes the Cynic

The tramp-as-divine-messenger archetype was embraced as a way of life by Diogenes the Cynic, who lived in a barrel in the Athenian marketplace to show to Athenians how little one needed to be happy. ‘Men might be happy, but such is their madness, they choose to be miserable’, he declared.

Civilization just makes us anxious and neurotic, terrified of public shame and desperate for public approval. Diogenes has liberated himself from that - he lives according to nature. Anything he does in private (going to the loo, masturbating) he is happy to do in public. He destroys the wall between his private self and public mask, thereby freeing himself from shame and self-division.

4) St Augustine and the beggar of Milan

In Book VI of his Confessions, Augustine is am ambitious young orator in Milan, on his way to a competition, eaten up with nerves about whether he will win or not. On his way, he walks past a beggar: ‘Already drunk, he was joking and laughing.’ This makes Augustine think of the vanity of worldly ambition as a route to happiness. ‘That beggar was [happy] already, while perhaps we would never achieve it...There was no question that he was happy while I was racked with anxiety.’ The encounter with the tramp is the beginning of Augustine looking beyond fame and ambition to try and find a more inwardly-substantial happiness, centred in God.

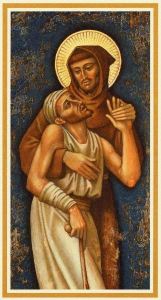

5) St Francis and the leper

There is a long tradition of ecstatic beggars in Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and probably many other religions. One of the most famous was St Francis, the playboy son of a rich silk merchant. One day, Francis was riding along, and he came across a leper. Francis decided this was ‘Jesus incognitio’, and he leapt off his horse and embraced the leper, which must have been a surprise for the leper. Francis then had a vision of Christ, telling him to embrace poverty in order to renew the church. This he did. His father is furious at him for giving away his inheritance, so he hauls Francis in front of the local bishop, who insists he give back his father’s possessions. Unperturbed, Francis strips off his clothes and hands them to the bishop. He carried on preaching poverty and love to humans and animals, and inspired the Franciscan Order, still going today.

6) Rumi and Shams Al-Tabriz

Another famous mendicant order was the Dervishes, a group of vagabonds founded by the mystic poet Rumi in the 13th century. Rumi was a celebrated Islamic scholar, who one day encountered a vagabond in the marketplace called Shams. They embraced and developed an intense spiritual (and possibly sexual) friendship, before Rumi’s followers killed Shams out of jealousy. Rumi fell into a depression, and then suddenly felt spiritually re-connected to Shams. He started to whirl, rotating slowly to attain a state of ecstasy, and began to recite lines and lines of immensely beautiful poetry.

Much of this ecstatic poetry is about encountering the Stranger - a marginal, sometimes frightening figure who calls us back to our immortality. We must, Rumi suggests, let go of the things of this world, of our desire for fame and respectability, in order to recognize the Stranger and remember who we are. Our troubles and even the figures in our nightmares are sometimes messengers sent from the Stranger, from the God within us. Rumi writes:

This being human is a guest house.

Every morning a new arrival.

A joy, a depression, a meanness,

some momentary awareness comes

as an unexpected visitor.

Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they're a crowd of sorrows,

who violently sweep your house

empty of its furniture,

still, treat each guest honourably.

He may be clearing you out

for some new delight.

The dark thought, the shame, the malice,

meet them at the door laughing,

and invite them in.

Be grateful for whoever comes,

because each has been sent

as a guide from beyond.

7) The Blind Beggar in Wordsworth’s Prelude

Beggars and vagabonds are a big feature of Romantic poetry, where they often represent the dignity, freedom and even divinity of rustic poverty, as opposed to the superficiality and imprisonment of the industrial city. Wordsworth, in particular, seemed to see beggars as holy figures, partly because they touch the hearts of other people with sympathy, and partly because they seem - as for Sophocles, Plato and Rumi - to be messengers from beyond. One instance of this is in Book Seven of the Prelude, when Wordsworth is in London, and is momentarily dazzled by the glamour of London affluence. Then he catches sight of the beggar, and it returns him to himself:

Amid the moving pageant, ‘twas my chance

Abruptly to be smitten with the view

Of a blind Beggar, who, with upright face,

Stood propp’d against a Wall, upon his Chest

Wearing a written paper, to explain

The story of the Man, and who he was.

My mind did at this spectacle turn round

As with the might of waters, and it seem’d

To me that in this Label was a type

Or emblem, of the utmost that we know,

Both of ourselves and of the universe;

And, on the shape of the unmoving man,

His fixed face and sightless eyes,I look’d

As if admonish’d from another world.

I love that phrase: 'a type / Or emblem, of the utmost that we know / Both of ourselves and of the universe'.

8) Magwitch from Great Expectations

Dickens also had a deep sympathy for the Outsider, the Stranger, the marginalized and forgotten figures of Victorian society. In Great Expectations, Pip has gone from country bumpkin to London gentleman thanks to a fortune bequeathed to him by a mysterious benefactor. Living surrounded by wealth and status, he has become embarrassed by his bumpkin origins.

Then, one day, he realizes he owes his wealth to an escaped convict called Magwitch, who he helped when he was a boy. Pip is faced with the choice between abandoning Magwitch or standing by him - and losing his reputation as a gentleman. Pip takes pity on the old tramp, and stands by him. He puts authenticity and compassion before the approval of other people.

9) The Little Tramp

During the Great Depression, tramps loomed large in western culture, whether in George Orwell’s Down and Out In Paris and London, or John Steinbeck’s stories of vagrants, bohos and itinerant workers. But the most magical tramp from that era is surely Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp - a ridiculous figure, but also plucky, kind, and with his own dignity. How many millions of people were helped through their troubles in the Depression by learning to laugh at and have compassion for the Little Tramp? What consolation and healing he brought!

10) The Fisher King

Coming in to our own era, the tramp has a particularly magical / alchemical role in the films of Terry Gilliam. Gilliam’s films are filled with broken and divided heroes longing for healing, and the tramp is sometimes a messenger of healing. In The Fisher King, Jeff Bridges’ character is a once-powerful media star who has fallen on hard times. He meets a tramp, played by Robin Williams, who is a bit mad but also quite sweet. The tramp is obsessed with Arthurian myths, and with trying to find the Holy Grail. Eventually, the two find it, sort of, and both find healing and grace. Robin Williams comes back from his exile in the wilderness, while Jeff Bridges, by taking pity on the tramp, finds a more authentic and ethical way to live.

11) Mulholland Drive

And finally, as a free bonus, and just to remind ourselves that the Shadow / Stranger / Outsider / Tramp is often a terrifying and nightmarish archetype, here’s the freaky beggar from David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, a film all about what happens when we get lost in our personae, and the figures from our nightmares start to impinge on our waking reality.

So that’s it for the top ten tramps. I know I’ve missed some out - Jean Renoir’s Boudou Saved From Drowning, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Eddie Murphy from Trading Places, and all the holy tramps who appear in Oscar Wilde’s short stories. Who are your favourite tramps?

The point I want to make is that I think the tramp figure may be some sort of daemonic messenger from the collective unconscious / God, sent to us when we have become lost in the masque of status, to bring us back to wholeness and spiritual equilibrium. The question is, do we have the courage to face it?

PS Since publishing this, people have reminded me of Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot - definitely tramps, not so definitely holy. Poor Tom in King Lear is a better candidate - Lear is redeemed, perhaps, by taking pity on the outcast. And apparently God appears as a tramp in Irvine Welsh' Acid House. Quote: "That c*nt Nietzsche wis wide ay the mark whin he said I wis deid"