PoW: Autarkia, Agonia, Anarchia, and other curious phenomena

Dark clouds are gathering once more over the financial markets. The Greek people have, like Diogenes, taken up permanent residence in the streets of Athens, to protest against the austerity measures demanded by the EU and IMF, and to deface the currency of the hated euro. Some economists think a sovereign debt default is likely, if not inevitable. If it happens, it will provoke another seizure of the global financial markets, potentially other sovereign defaults and bank insolvencies, and perhaps even the collapse of the euro.

Dark clouds are gathering once more over the financial markets. The Greek people have, like Diogenes, taken up permanent residence in the streets of Athens, to protest against the austerity measures demanded by the EU and IMF, and to deface the currency of the hated euro. Some economists think a sovereign debt default is likely, if not inevitable. If it happens, it will provoke another seizure of the global financial markets, potentially other sovereign defaults and bank insolvencies, and perhaps even the collapse of the euro.

I personally believe you should, as a person or a country, try to honour your debts. But if this is simply impossible, then you can try to negotiate a restructuring with your creditors - this is in your creditors interest as well, because they want to get at least some money back. To initiate a restructuring of your debt (which is what a default basically is) is not necessarily 'economic suicide' as some commentators suggest. Argentina defaulted in 2002, and is already able to access the international debt markets again today. Russia defaulted in 1998, and was rated investment grade again by 2003. But Greece is a member of the European monetary union, and defaulting would severely weaken investors' confidence in the euro and in other European government bonds.

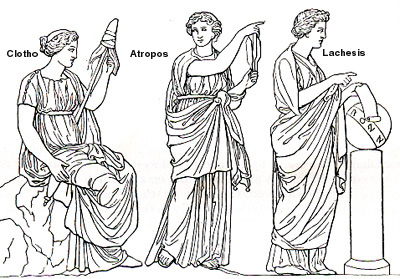

The German government, desperate to keep the euro project together, is trying to negotiate a 'soft restructuring' of Greece's debt with bondholders, which means persuading bondholders to take some of the pain of the bail-out along with European tax-payers. This is absolutely the right thing to do - private bondholders should pay the price for making a poor investment decision in Greece. It is very unjust that tax-payers had to bail out private banks and their bondholders during the Credit Crunch, and then had to slash our public services to pay the bill.  But Merkel faces opposition for her plan from the international credit rating agencies (Moody's, Fitch and Standard & Poor's) who say they will treat any 'soft restructuring' as a Greek default, which could precipitate panic selling of other European government bonds, which in turn could bankrupt some European banks. Another reminder of the ridiculous power that the three rating agencies have over our economic and political lives. They're like the three Fates of ancient Greek myth - except we can abolish these particular fates rather than being ruled by them.

But Merkel faces opposition for her plan from the international credit rating agencies (Moody's, Fitch and Standard & Poor's) who say they will treat any 'soft restructuring' as a Greek default, which could precipitate panic selling of other European government bonds, which in turn could bankrupt some European banks. Another reminder of the ridiculous power that the three rating agencies have over our economic and political lives. They're like the three Fates of ancient Greek myth - except we can abolish these particular fates rather than being ruled by them.

The rating agencies are unelected, unregulated, incompetent, and even corrupt - the SEC has just opened civil fraud charges against them for their role in the sub-prime mortgage crisis. They do more harm than good, because investors outsource credit analysis to them rather than doing the work themselves. They encourage herd movements of the market. And they often get it wrong. The Nobel-prize winning economist Amartya Sen argues here that we should stop letting them lord it over governments.

Meanwhile, in Athens, nationalist sentiment is on the rise - who wants to be bossed around by the Germans and the IMF, after all. It's also on the rise in Germany - why should they bail out these profligate Greeks who can't control their spending and who blame Germany for their ills? In fact, nationalism is on the rise right across Europe. Belgium has now been without a government for a year, because Flemish nationalists refuse to join a coalition and want to separate from the rest of Belgium. The international federation of Europe is breaking back down to the level of the nation-state, and in some instances (Greece, Belgium) the nation-state is also breaking down to the local level.

This can feel exciting, invigorating - power devolves from the international to the national and finally to the local level. Costas Douzinas, a professor at Birkbeck, thinks the protests in Greece are 'the closest we have come to democratic practice in recent European history'. He writes: "A motley multitude of indignant men and women of all ideologies, ages, occupations, including the many unemployed, began occupying the central square of Athens opposite parliament...Calling themselves the 'outraged', the people have attacked the unjust pauperizing of working Greeks, the loss of sovereignty that has turned the country into a neocolonial fiefdom of bankers, and the destruction of democracy. Their common demand is that the corrupt political elites who have ruled the country for some 30 years and brought it to the edge of collapse should go."

This can feel exciting, invigorating - power devolves from the international to the national and finally to the local level. Costas Douzinas, a professor at Birkbeck, thinks the protests in Greece are 'the closest we have come to democratic practice in recent European history'. He writes: "A motley multitude of indignant men and women of all ideologies, ages, occupations, including the many unemployed, began occupying the central square of Athens opposite parliament...Calling themselves the 'outraged', the people have attacked the unjust pauperizing of working Greeks, the loss of sovereignty that has turned the country into a neocolonial fiefdom of bankers, and the destruction of democracy. Their common demand is that the corrupt political elites who have ruled the country for some 30 years and brought it to the edge of collapse should go."

Douzinas thinks the protests have led to the revitalization of genuine popular democracy: "The parallels with the classical Athenian agora, which met a few hundred metres away, are striking. Aspiring speakers are given a number and called to the platform if that number is drawn, a reminder that many office-holders in classical Athens were selected by lots. The speakers stick to strict two-minute slots to allow as many as possible to contribute. The assembly is efficiently run without the usual heckling of public speaking. The topics range from organizational matters to new types of resistance and international solidarity, to alternatives to the catastrophically unjust measures. No issue is beyond proposal and disputation. In well-organized weekly debates, invited economists, lawyers and political philosophers present alternatives for tackling the crisis. This is democracy in action."

Perhaps - but it's difficult to practice that sort of loose popular democracy at the national level. And when you have disorganized, chaotic assemblies of arguing representatives, the danger is that an enterprising few seize power and enforce a dictatorship, like Robespierre, Lenin, General Franco, or indeed the Junta that ruled Greece from 1967 to 1974. Representative democracy is rotten, but it's a whole lot better than military dictatorship.

Talking of local democracy in action, I spent last weekend up in Liverpool attending and enjoying the Philosophy In Pubs (PIPs) first conference. PIPs was started by three working class Liverpudlians who wanted to give ordinary people the chance to come together and learn how to practice philosophy. One of its founders, Rob Lewis, told me his life had turned around when he did a philosophy course while unemployed: "Doing philosophy is a way of overcoming the sense of alienation that many of us feel at times, which comes from being in a society that wants to measure you in very limited ways and then judge you to see what shaped hole you might fit into and what life chances you might be worthy of."

The PIPs approach is to try and establish 'communities of inquiry' who collectively investigate an issue and explore it, rather than trying to defeat each other's arguments. It's an approach I like and try to do myself, but not one the ancient Greeks necessarily practiced. Didn't Socrates typically attack and demolish his interlocutors' arguments? The Socratic dialogues seem to be a perfect example of the Greek practice of 'agon' - philosophy as a gladiatorial contest between two speakers. At the London Philosophy Club next week, we consider the relationship between rhetoric and philosophy - are they allies, or enemies? Should we try and discover the truth in philosophical dialogues, or simply destroy our opponents?

We're evolutionarily programmed to do the latter, argues an interesting new paper by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber. We reason, the authors argue, not to discover the truth, but to defend our assumptions, demolish the opposition, and persuade the public. Reasoning is inherently gladiatorial, that's why people love to see speakers like Christopher Hitchens (on fine form debating the after-life in this video), and why they post delighted comments on videos of his debates saying 'smackdown!' or 'you just got pwnd!' and so on. We don't go to debates to try and discover the truth. We go to listen to our nominated idea-gladiators battle for our beliefs. That's why the debate between atheists and believers, or between Republicans and Democrats, or between Labour and Tories, is often so vitriolic. We engage in politics to see our position defended and the opposition put to the sword.

We're evolutionarily programmed to do the latter, argues an interesting new paper by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber. We reason, the authors argue, not to discover the truth, but to defend our assumptions, demolish the opposition, and persuade the public. Reasoning is inherently gladiatorial, that's why people love to see speakers like Christopher Hitchens (on fine form debating the after-life in this video), and why they post delighted comments on videos of his debates saying 'smackdown!' or 'you just got pwnd!' and so on. We don't go to debates to try and discover the truth. We go to listen to our nominated idea-gladiators battle for our beliefs. That's why the debate between atheists and believers, or between Republicans and Democrats, or between Labour and Tories, is often so vitriolic. We engage in politics to see our position defended and the opposition put to the sword.

All of which has worrying implications for media objectivity. Do we want to discover the truth through our media, or just watch Jeremy Paxton beat up some hapless politician? Do we want civil debate, or the sort of vicious gladiatorial combat that American political television has become? An interesting proposal for media reform comes from Dan Hind, whose new book The Return of the Public came out this year. Hind suggests our media has become captured by the ruling financial and political elite, and fails to hold it to proper account. So the public need to seize control of the means of information. Hind suggests this should happen through 'public commissioning' - the public says what it wants to read about, and public money is distributed to journalists who make pitches for their work.

Hind doesn't say where the work would appear, though. In newspapers? On TV? Why should private news proprietors run stories they didn't pay for? One alternative, it seems to me, is offered by the development of electronic reading devices like Kindle. On such devices, the reader can become editor, creating their own newspaper. They can buy articles directly from investigative journalists, without the need for a paper to intermediate - and can finance longer investigations through contributions. It might make sense, in such a marketplace, for investigative journalists to pool their talents into investigative journalism 'boutiques'. Already, some of the finest journalism we have follows this model, such as This American Life, which is funded by public contributions, or Adbusters magazine, whose founder, Kalle Lasn, I interviewed here.

The interview with Lasn was actually done back in 2002, when the financial markets were in crisis yet again. Lasn said then: "God knows what will happen after the next paradigm shift or after this next cultural revolution. We will be left with a grim situation where climate change is out of control, and we may be in a situation like the 1930s where our economic system is in tatters. And then from the bottom up we'll have to build a new system, and at the moment, I have no idea how that system will look." Will it be like waking from a dream, I asked him. "Yeah, I think so. All of a sudden people will wake up one day, after the Dow Jones has gone down by 7,000 points, and say: 'What the fuck is going on?' They'll just see their life as they know it collapse around them. And then they'll have to pick up the pieces and learn to live again." Cheery stuff!

See you next week,

Jules