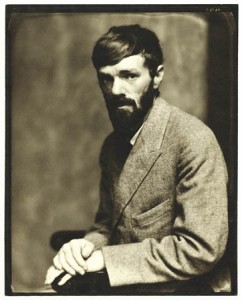

PoW: On Dionysus, DH Lawrence, the death complex, and other curious phenomena

DH Lawrence was my favourite author when I was an adolescent, ever since my grandmother gave me my grandfather’s editions of his complete works. I loved the way Lawrence described ordinary Midlands life with an Old Testament reverence, the depth of inner life he accorded to Ursula in The Rainbow, how he followed her soul through its crises and unfoldings. The BBC has just made a new adaptation of The Rainbow and Women In Love, by the way, complete with male naked wrestling.

I really loved Lawrence, more than any other writer. I wanted to specialize in him for my Oxford entry exam, but was told I couldn’t, because he was unfashionable and ‘probably gay’. So I had to do a Caribbean poet instead. I chose the college I studied at, Worcester College, because the English tutor there, David Bradshaw, is an expert in DH Lawrence - he edited the Oxford edition of Women In Love.

My two favourite books at that age were Lawrence’s Rainbow and Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy. Heavy stuff! Both presented an irrationalist, Dionysian view of the psyche. We have become too rational, too conscious, they argued. We live too much in our head, and need to re-connect, in a mystical way, to the deep unconscious sources of our being: to our body, to our sex, to our blood, to our unconscious. The villain in their story is Socrates, and all the technocratic rationalism that he brought into western civilization, like a sickness.

Lawrence and Nietzsche were two small, weak, weedy, chronically-ill writers who nevertheless made a cult of health, strength and wholeness. They were both incredibly intolerant of sickness, weakness or woundedness. You often meet wounded male characters in Lawrence’s novels - Anton in The Rainbow, Gerald in Women In Love, Lord Chatterly in Lady Chatterly’s Lover - and they are typically treated with a complete lack of pity. We hear that they are ‘dead’, ‘broken’, ‘empty’, ‘lifeless’, and so on.

These characters often suffer from something like Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (so much of modernism, from Hemingway to TS Eliot, is really about the attempt to put yourself back together after trauma has broken you apart), and Lawrence suggests there is no cure for this woundedness, that the characters will never get better, and should simply accept they are broken and embrace their secret longing for death. They should kill themselves, as Gerald does at the end of Women In Love.

It eventually became unbearable for me to read him, because I was myself suffering from PTSD at university, and was terrified that I was permanently broken, and should simply kill myself too. It seemed to me that, according to Lawrence, there was no hope, I should accept that I had fatally wounded my Dionysian ‘life-force’, and should embrace annihilation. When you have PTSD, you become trapped in negative, obsessive thoughts - I decided I was stricken with the modern sickness of over-thinking that Lawrence saw all around him. I had become too conscious, too stuck in my head. I couldn’t re-connect to my unconscious...I was broken, empty, dead.

But I didn’t kill myself. Instead, after a few years, I managed to get better thanks to ancient Greek philosophy and CBT, which showed me that what was causing me suffering was not a psychic wound in my Dionysiac life-force, but my own beliefs. Through a Socratic process of self-examination, I became aware of my beliefs, and learnt how to change them. I got better through Apollo, not Dionysus.

Lawrence would hate CBT. He would hate it. He would say ‘it’s all in the head, in rationality, it doesn’t connect to the deep springs of our life-blood’ (or some such guff). He would say ‘it’s not the cure for our modern malaise - it’s the sickness itself. It’s just another attempt to control the savage beast of our psyche using our technocratic reason. It’s the machine.’

The difference between me today and me in my late teens and early twenties is I am far less likely to fall for that sort of Romantic obscurantism. I mean...I do still believe in the soul, the unconscious, the imagination. But I think Lawrence, Nietzsche, Freud, Jung and the other irrationalists of that era put the cart before the horse. Our dream-life, our unconscious, our limbic system, follows our thoughts and beliefs. If our beliefs are toxic, then our entire psychic life will be toxic. And if you want to get healthier, you cannot do it by trying to escape your head, by trying to become an unconscious savage somehow, as Lawrence tried to do. The answer is not to escape conscious thinking. It is to stop thinking stupidly, badly, destructively. When you do that, it means you can free your psyche from over-thinking. You can start thinking less, and instead simply enjoy the moment, the body, the flow.

At the same time, the Socratic rationalist approach to the psyche has its obvious limits. We remember that, towards the end of his life, Socrates’ daemon told him to learn to play music. It was a recognition, perhaps, that his rational approach to life had missed something out, that the gods of Dionysus and Orpheus must be given their due, as well as Apollo. Lawrence was right, perhaps, to emphasize the body, and that body-knowledge we get sometimes when we are dancing, or making love, or playing sport. Socrates and the Stoics tell us the body is a prison. I don’t think so. It is something wonderful.

So, um, here are some more links:

This is consciousness researcher Sue Blackmore talking about how LSD forces us to confront ourselves.

This is a piece I did for the School of Life's blog, on teaching the Good Life in schools.

This is Prospect editor David Goodhart’s excellent Radio 4 analysis programme about the rise of Blue Labour and its leading thinker, Lord Maurice Glasman of Stoke Newington. Glasman is our speaker at the London Philosophy Club on Monday. Can’t wait!

Glasman says that our economy has been captured by private banks. Lefty nonsense? Not necessarily. Here’s an unusual Economist story, arguing that the economic recovery is mainly benefitting the rich, and that living standards are falling because our society has become captured by the banks. Go Economist!

Some accuse Glasman’s brand of nationalist communitarianism as pandering to working class anti-immigration prejudice. Meanwhile, nationalism continues its heady rise on the continent. Here is a Spectator piece on the rise of Marine Le Pen in French politics.

The European sovereign debt crisis has started again, with Portugal close to a bail-out and Belarus also nearing debt default. Here’s a decent New York Times piece summing up where we are at the moment.

Here is an Economist review of a good-sounding book about physics and the nature of reality by David Deutsch.

And finally, here is the latest from the Reddit ‘Ask Me Anything’ column: ‘I’m a 4-year-old, ask me anything’. Pretty funny.

See you next week,

Jules