Review: The Wellness Syndrome

How are you feeling? How well are you? Is your weight where you want it to be? Smoking too much? How happy are you on a scale of one to ten? Are you optimising your personal brand? How fast was your last five kilometre run? Would you like to share that via social media? Would you like a life-coach to help you overcome these challenges on a way to a better, happier, more awesome you?

If such questions fill you with dread, don’t worry, you're not alone. We have become a culture of Bridget Joneses, anxiously pursuing an ever-retreating ideal of wellness. The ruling ideology of our time, argue Carl Cederstrom and Andre Spicer, is ‘the wellness syndrome’, which makes the urge to self-improvement a moral imperative, and our own bodies the battleground.

Cederstrom and Spicer thinks the wellness syndrome is a mistake and a trap, for three reasons. First, it is based on a foolish myth of the individual as ‘neoliberal agent’, able to exert perfect control of their body, their emotions and their life. If you’re poor or fat or unhappy, it’s your fault, and you need some life-coaching or military fitness boot-camp to get into shape. This is a convenient shifting of personal responsibility from the state onto us hapless Bridget Joneses.

Secondly, the constant search for personal authenticity and fulfillment is deeply narcissistic. Aristotle and Rousseau's eudaimonic society was about fulfillment through civic activity. Rousseau would be 'apalled' by our culture’s 'blind celebration of individual narcissism’ (really? Have you read his Confessions? But let’s press on.)

Thirdly, the dream of autonomy and authenticity we’re chasing is a mirage - in fact, the wellness syndrome is deeply conformist, and the ultimate aim of all this self-improvement is simply to make us more productive and sellable in the capitalist marketplace. We think we’re becoming more ourselves, when in fact we’re becoming more alienated.

The way to rebel against the wellness syndrome, the authors argue, is to embrace illness and impotence. Live like Sartre’s students, who existed on a diet of ‘cigarettes, coffee and hard liquor’. Take sick days. Over-eat. Go ‘barebacking’ - a culture in which ‘bug-chasers’ (people who want to get HIV) have unprotected sex with ‘gift-givers’ (people who have the illness).

Cederstrom and Spicer are professors of organizational theory and organizational behaviour, respectively. However, this book is basically a rant, like an extended Spectator column by Rod Liddle, moving effortlessly from anecdote to rumour, without ever troubling itself with scientific evidence.

We are told the anecdote of the two life-coaches who killed themselves in a suicide pact. Why did they kill themselves? We’re not informed, but it seems damning, and we move on. We’re told David Cameron is a fan of Rhonda Byrne’s The Secret. Really? Well, a Guardian columnist said so, let's move on. We’re told the Wellness Syndrome leads to an obsession with dieting and personal fitness. Then why, if this is the ruling ideology of our time, are 67% of men and 57% of women in the UK overweight or obese? And why is the sex addict in Steve McQueen’s Shame also an example of the Wellness Syndrome? We’re never told - move on to the next anecdote.

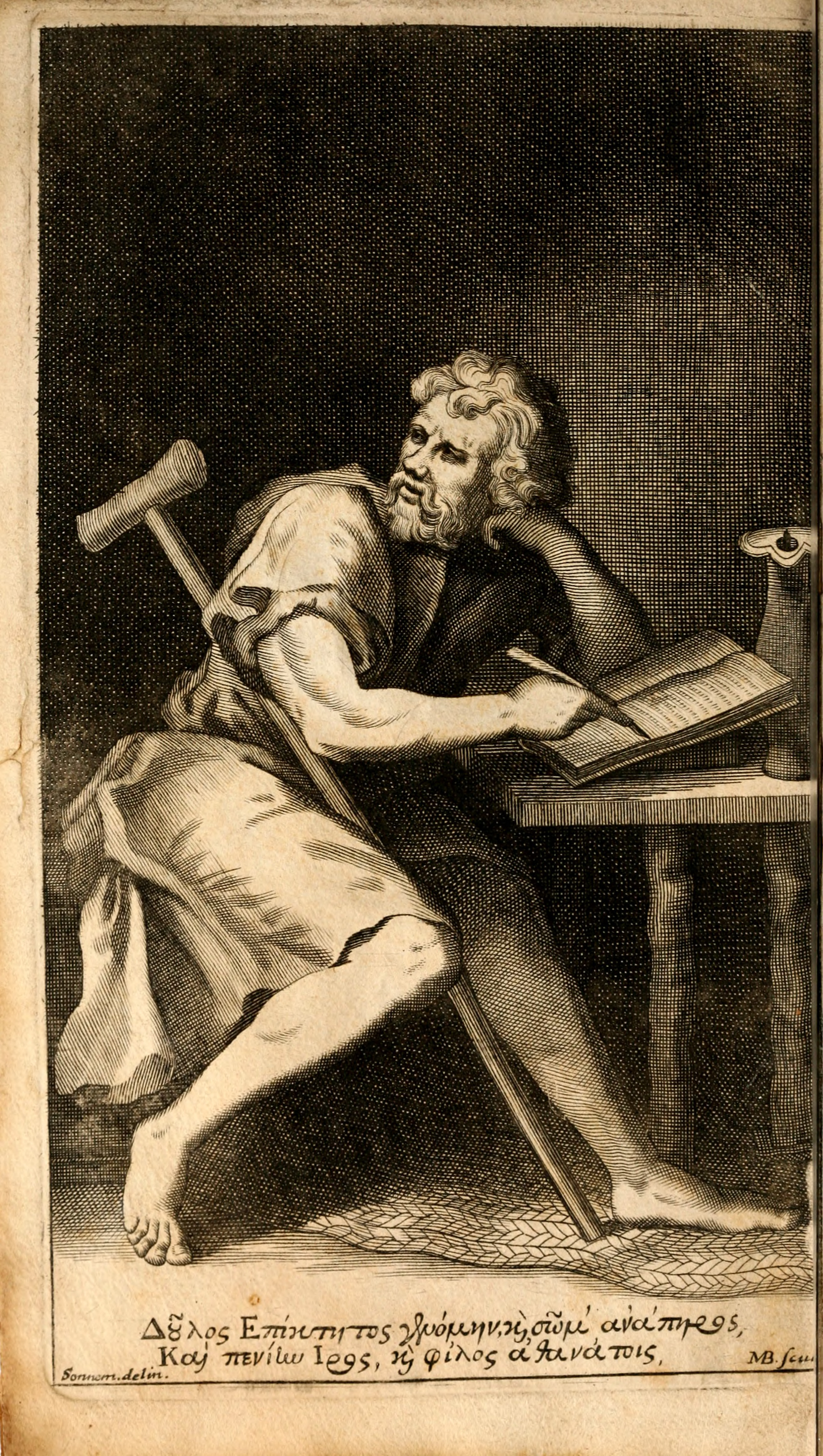

The core claim of the book - that we’re being sold a toxic idea of neoliberal personal autonomy - deserves more careful examination, because it has some validity. The roots of this model of personal autonomy lie not in neoliberalism, in fact, but in Stoicism, and particularly in Epictetus, who was a sort of life-coach for Roman aristocrats, urging them to take responsibility for their thoughts and beliefs in order to heal their emotions and improve their selves. ‘It’s not events which cause humans suffering, but our opinion about events’, he insisted. And our opinions are always in our control. 'The robber of your free will does not exist'. This Stoic libertarian ethos fed into Enlightenment liberalism, into Victorian self-help, and into the modern wellbeing movement and the idea - at the heart of cognitive therapy and Positive Psychology - that our emotions are our choices, and that 'there is nothing more tractable than the self', as Epictetus put it.

Of course, Epictetus’ philosophy can be taken too far. The Stoics focused entirely on the individual, and ignored society. They thought a wise individual could be free and happy even in the midst of a toxic and unequal society (Epictetus himself was a slave). Most of us are not such citadels of serenity. That’s why there’s a strong correlation between poverty and depression. Shit gets us down. So it’s unfair and unwise to make people’s emotional or behavioural problems entirely their responsibility - our personal agency is weak, at best. Most of us are to some extent the creatures - Epictetus would say the slave - of our circumstances.

And yet Epictetus was not entirely wrong. Overcoming problems like depression, or alcoholism, or obesity, or injustice, or even poverty does involve personal agency. Humans do have a capacity not just to be determined by our circumstances, but to determine our own attitude to them, and through that self-determination we can get the inner strength to change our external circumstances. We don't always have to resort to pill-popping to feel better (oddly, despite its cover, the book doesn't ever look at our growing dependence on mood-altering pills, perhaps because that doesn't fit with their rant against 'the myth of neoliberal agency').

Our powers of self-determination don't necessarily have to be in the service of neoliberal capitalist conformity. Look at Gandhi, practicing swaraj or ‘self-governance’ in his personal life order to prove to the British Empire that Indians are not irresponsible children. Look at Nelson Mandela, reading the Stoic poem Invictus to himself while practicing ascetic self-government in Robben Island prison, to prove that black South Africans can govern themselves with dignity.

Of course, the strength or weakness of our personal agency, the extent to which it is tied up with determining factors like our environment or genes, is a very difficult question. I recently saw the documentary Amy, and was moved by the story of Amy Winehouse’s rapid self-destruction. Whose fault was it? Whose responsibility? Was it the father, for not being there when Amy was growing up, and then trying to cash in when she was famous? Was it her boyfriend, latching on and encouraging her drug dependence? Was it our celebrity-obsessed media and culture? Yes, perhaps, all of these things. But it was also Amy’s doing.

But can you say an addict ‘chooses’ to destroy themselves? To what extent does a person with mental illness really make choices? To some extent. As that famous sex-addict, St Augustine, explored in his Confessions, we make choices, which then harden into the chains of habit and addiction. Those chains are very difficult to break. It’s even harder today, when the internet remembers our habits and reflects them back to us. But change is possible. And personal choice is an important part of that liberation.

Our degree of personal agency, then, our capacity to determine our course in life, is a very complicated area, but it is one that psychology has spent decades trying to explore, through cognitive behavioural therapy, social psychology, behavioural economics, self-determination theory, and the psychology of self-control. And psychologists have begun to build up evidence that personal autonomy is limited but nonetheless real - Epictetus was, to some extent, right.

Yet Cederstrom and Spicer don’t cite a single piece of scientific evidence in their rant against personal autonomy. The closest we get is an appeal to authority: ‘We know from Freud’, ‘we know from psychoanalysis’. Do we? At one point they write: ‘As pointed out in a Huffington Post article, mindfulness advocates often make unsubstantiated claims.’ Oh the irony.

Because the authors set out to write a polemic, they make broad and usually damning generalizations, and ignore the good aspects of the phenomena they dismiss. For example, one of their favourite targets is the self-tracking movement, in which people use self-tracking devices to measure various aspects of their life, to improve them. This, the authors say, is just neoliberal alienation. Well, it can be, but not always. Self-tracking can be a way for people to empower themselves and become experts in their own health, rather than relying on the authority of external experts. One well-known self-tracking app is MoodScope, which Jon Cousins invented to help himself track his depressive episodes to see what helped him get better. He then made it freely available to other people. This seems to me worth applauding.

Finally, I’m not convinced that the moral ideology of wellness and health is a new thing. Health has always been ideological. Look at Plato’s Republic, with its diagnosis of the sick society and the healthy society. Look at the Middle Ages, with its public performances of the Seven Deadly Sins, including Gluttony. Every ideology involves some positive model of human flourishing, including Neoliberalism and Marxism. If the best model of flourishing you can offer is sick days and barebacking, why should we follow you?