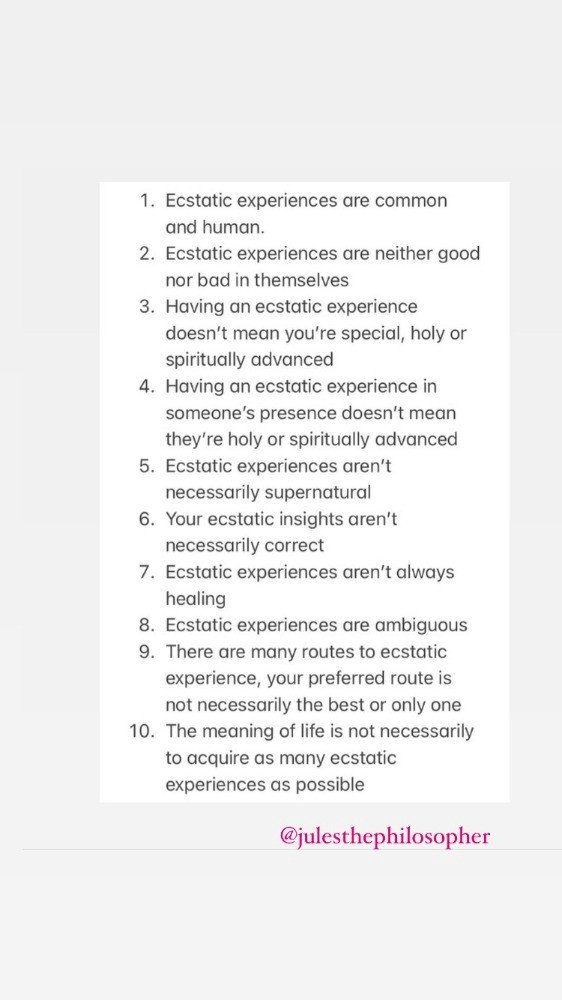

Ten principles for making sense of ecstatic experiences

Western culture urgently needs to improve its cultural resources to help people make sense of ecstatic experiences. Evidence suggests that more and more people in western culture are having and seeking ecstatic experiences, because of the growing popularity of psychedelics and contemplative practices like meditation and yoga. However, we have scant cultural resources for making sense of such experiences.

Ordinary people who have ecstatic experiences have very few places to go for information about them. This means they will turn to secular psychiatrists, who may pathologize their experience, or to religious or spiritual influencers, who often have self-serving or conspiritualist agendas. Ecstatic experiences can be healthy and healing, but they can also be dangerous both for individuals and their societies. We urgently need a more mature cultural understanding of ecstatic experiences, to support individuals and the health of the body politic.

Here are ten principles to help people make sense of ecstatic experiences (with thanks to BuddhaMemeFolder and Healing from Healing for the memes).

1) Ecstatic experiences are common and normal

An ecstatic experience is a moment where the mind goes into an altered state of consciousness and one’s ordinary sense of self and reality changes. Historically, such experiences tended to involve a feeling of ego-dissolution (ecstasis literally means ‘standing outside’ your usual self) and a feeling of ‘enthusiasm’ — a god or spirit enters you. The anthropologist Erika Bourguignon found that 90% of human societies had institutionalized rituals for the attainment of altered states of consciousness. Humans seek ecstatic experiences for meaning, healing, religious worship, creativity, social connection, and fun.

Most cultures have seen ecstatic experiences as potentially dangerous and disruptive, hence they devised rules and rituals to manage them for the good of individuals and society. Modern western culture, unusually, sought to marginalize and pathologize ecstatic experiences entirely. They were associated with delusion, madness and psychosis. And it’s true that ecstatic experiences can be akin to temporary psychosis. However, other cultures have suggested this temporary madness can have benefits for an individual and their society, if properly managed.

Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. Modern western culture sought to marginalize and pathologize ecstatic experiences, which most other cultures recognized as both potentially harmful and also potentially valuable

2) Ecstatic experiences are neither good nor bad in themselves

They are amoral. They have no essential moral content. They involve a range of psychological states which can be put to all kinds of different moral and ideological ends. This point was well made by the philosopher Slavoj Zizek, who explored how Beethoven’s ecstatic Ode to Joy was used by a whole variety of political ideologies, from the EU to Nazi Germany.

3) Having an ecstatic experience doesn’t necessarily mean you’re special, holy or spiritually advanced

Ecstatic experiences are normal and common. Some people have them every day. Some personality types are more prone to them. Having an ecstatic experience or many ecstatic experiences does not mean you’re special, holy or spiritually advanced, and not having such experiences doesn’t mean you’re missing out.

It can feel like you’re special after having an ecstatic experience — that’s one of their allures. In some cultures certain types of mental state are taken as proof of your spiritual advancement. However, one of the risks of ecstatic experience is ego inflation — thinking you’re uniquely blessed, divinely chosen, elect, highly evolved, or even the Messiah. This risk is particularly acute in a culture like New Age spirituality, where spiritual literacy (ie a passing familiarity with terms like samedhi or jhana) far outstrips spiritual maturity.

4) Having an ecstatic experience in someone else’s presence doesn’t necessarily mean they’re holy or spiritually advanced

One of the biggest triggers for ecstatic experience is the expectation of having an ecstatic experience. That’s why people who go to see a spiritual teacher with the expectation of an ecstatic encounter may indeed have an ecstatic encounter, which they then take as proof of the holiness or even supernatural power of that teacher. In addition, teachers may develop techniques to enhance their own charisma and the suggestibility of their followers, such as eye-staring, sleep deprivation, hypnotic techniques, the use of psychedelics, and so on. History is full of examples of gurus whose followers thought they were highly spiritually advanced, and who often experienced ecstatic experiences in their presence, yet they turned out to be abusers, swindlers, criminals and psychopaths. Having an ecstatic experience in someone’s presence is not reliable evidence of their sanctity.

5) Ecstatic experiences aren’t necessarily supernatural

It’s impossible for the sciences or humanities to say, let alone measure, to what extent an ecstatic experience really is from God, the spirit world or some sort of higher intelligence. Suffice it to say that most mature religious traditions suggest that not all ecstatic experiences are necessarily from God or the spirit world. Christian theologians like Jonathan Edwards, who wrote during the 18th century ecstatic movement known as the Great Awakening, came to the conclusion that some ecstatic experiences are the result of psychology — social contagion, for example, or an over-excited imagination. There are a variety of different possible explanatory frameworks for ecstatic experience, some supernatural and some naturalist. Some naturalist frameworks still recognize potential benefits to ecstatic experiences, without thinking they involve God or the spirit world.

6) Your ecstatic insights aren’t necessarily correct or valuable

They can feel totally true and revelatory. Indeed, that’s one of the characteristics of ecstatic experience, as William James pointed out. And sometimes, the truths or insights revealed in ecstatic experiences have stood the test of time, and proven of sustained value for the arts, sciences or culture. However, there are also countless examples of ecstatic experiences which proved to be unreliable or simply nonsense. Oliver Wendell Holmes Senior once experimented with ether to try and discover ultimate truths. He wrote:

The veil of eternity was lifted. The one great truth which underlies all human experience, and is the key to all the mysteries that philosophy has sought in vain to solve, flashed upon me in a sudden revelation. Henceforth all was clear: a few words had lifted my intelligence to the level of the knowledge of the cherubim. As my natural condition returned, I remembered my resolution; and, staggering to my desk, I wrote, in ill-shaped, straggling characters, the all-embracing truth still glimmering in my consciousness. The words were these (children may smile; the wise will ponder): ‘A strong smell of turpentine prevails throughout.’

7) Ecstatic experiences are ambiguous

Ecstatic experiences are ambiguous. They can both feel like a flood of meaning, and leave people trying to make sense of them for years. They can feel both enlightening and bewildering. They can move from euphoric to terrifying in minutes. They are dynamic, paradoxical, ‘both-and’ rather than ‘either-or’, and not easily captured in logical propositions or quantitative questionnaires.

Western culture in the last 300 years has tended to take a rather immature, black-and-white view of ecstatic experiences, seeing them either as wholly delusional or wholly holy. One still finds this immature attitude in charismatic Christian churches, where holy spirit encounters are seen as totally good and their meaning is seen as totally transparent. Such experiences are rapidly converted into dogmatic testimonials for the church where they occurred. Something similar occurs in the emerging science-religion of psychedelics — people’s experiences are seized on and rapidly converted into dogmatic testimonials for the movement. All ambiguity is collapsed into soundbite headlines like ‘I’ve never felt such joy’ or ‘the most meaningful experience ever’. Psychedelic science even uses a ‘mystical questionnaire’ to give ecstatic experiences a score out of ten according to how ‘complete’ it is.

A mature culture, by contrast, respects the ambiguity of ecstatic experiences and recognizes that something in these experiences defies easy interpretation, classification or analysis. Even in religious cultures which see ecstatic experiences as potentially revelatory, it is still understood that they are ambiguous, and one should be careful before interpreting them too quickly or literally. As the religious studies scholar Jeffrey Kripal has suggested, ecstatic experiences can be seen as texts, with multiple levels of meaning and symbolism. A mature culture recognizes these multiple possible levels and is wary of collapsing ambiguity into one simplistic interpretation.

8) Ecstatic experiences aren’t always healing

The emerging science-religion of psychedelics, like Christianity, has made very strong claims about the saving power of the psychedelic experience, leading countless people to look to these experiences to rescue them from their mental, emotional and existential problems. And for some people, ecstatic experiences (whether via psychedelics or other avenues) can be genuinely healing and life-changing. But it’s not always the case. Ecstatic experiences sometimes don’t totally ‘heal’ a person from, say, PTSD or depression. Or they may only give temporary release from habitual ego patterns, which then subsequently re-assert themselves.

Most religious traditions suggest that occasional ecstatic experiences need to be followed up by daily practice of some kind, to turn altered states into altered traits of personality. Even then, it might not ‘work’ in the sense of healing you of all your problems.

Occasionally, ecstatic experiences can cause or exacerbate mental health problems, triggering temporary or long-term psychosis, for example, or leaving a person feeling more confused and disconnected from consensus reality than before the experience. Some of these more difficult ecstatic experiences (sometimes called ‘spiritual emergencies’ or ‘dark nights of the soul’) can be resolved with therapy or other methods. But not always.

9) There are many routes to ecstatic experience, and your preferred route is not necessarily the best or only one

Ecstatic experiences can open one’s mind and increase epistemic flexibility, but they can also close one’s mind and lead to dogmatic exclusivism — your route to ecstatic experience is the best route and even the only route. Accept no substitutes. This dogmatic exclusivism is often exacerbated, of course, by religions and churches, who seek to establish monopolies on ecstasy, like the Christian emperor Theodosius, who closed down all non-Christian cults throughout his empire. Even today, one sees a form of psychedelic exclusivism in some psychonauts — only psychedelics grant a true revelation of the divine, and perhaps only their preferred drug grants a true revelation. Everyone else’s non-pharmacological route to ecstatic experience is a poor and phony substitute. No. There are infinite routes to ecstatic experience. Some routes may be easier or more reliable than others, but that doesn’t make them necessarily better or more truth-revealing.

10) The meaning of life is not necessarily to have as many or as powerful ecstatic experiences as possible

Both in Christian and New Age cultures, one can see a tendency to fetishize ecstatic experiences, to see them as the ultimate meaning and goal of life, and to try and consume as many of them as possible. This is also a heritage of the Romantic movement, which placed a huge value on occasional ecstatic experiences.

This excessive emphasis on ecstatic experiences can be unhealthy, and lead to a denigration of ordinary life. There is such a thing as addiction to ecstatic experiences, and spiritual bypassing of unpleasant facts. Ecstasy-chasing can also be profoundly selfish. A mature culture sees ecstatic experiences as normal and human moments, which may occasionally be intentionally sought for purposes of healing, meaning, connection or fun. But they’re transient, ambiguous experiences and certainly not the entire meaning or goal of life. An immature culture is obsessed with such experiences and places too high a value upon them.

Finally, here is an incomplete list of books I’ve found useful on this topic:

William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience (still the best book on the topic, it laid the groundwork for a psychology of ecstatic experiences, although it showed a strong individualist bias)

Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (this book recognized the communal importance of ‘collective effervescence’ for bonding societies together)

Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind (this recent work of social psychology builds on Durkheim to explore how ecstatic experiences bind us together, but Haidt also recognizes this communal binding can be dangerous and delusional)

Barbara Ehrenreich, Dancing in the Streets (the popular sociologist has explored ecstatic experiences in several of her books, including the ecstasy of war and violence in Blood Rites, her own ecstatic experience in Living with a Wild God, and this exploration of ecstasy through collective dancing).

Aldous Huxley, Moksha (Huxley shaped our cultural understanding of psychedelics — indeed, he helped to coin the word. He was unrivalled in his ability to think about ecstatic experiences at multiple levels, from the chemical to the psychological to the historical, cultural and political).

Ann Taves, Fits, Trances and Visions (a very good study of changing historical attitudes to ecstatic experiences in the US from the 18th to the early 20th century)

Jeffrey Kripal, The Flip (Kripal is a pioneer of the ‘mystical humanities’ and has long emphasized the need for a careful hermeneutics of contemporary ecstatic experiences, in which we read such experiences as cultural texts, while also being open to their mysteriousness)

Sam Harris, Waking Up (a good naturalistic account of spiritual experiences, and a recognition by a leading atheist of their importance and value)

Stanislav and Christina Grof (editors), Spiritual Emergency (this important collection of essays explores spiritual experiences which are psychologically difficult, disturbing and even quasi-psychotic, and how such experiences can best be managed by individuals and therapists).

Isabel Clarke (editor), Psychosis and Spirituality (this is a great collection of essays on the overlap between psychosis and spirituality).

Charles Tart (editor), Altered States of Consciousness ( a pioneering collection of psychological essays from 1969)

Carl Jung, Man and his Symbols (ecstatic experiences sometimes involve symbolic and mythological content, which can be interpreted psychologically, as Jung first explored)

Michael Pollan, How To Change Your Mind (the book that helped to spark the current psychedelic renaissance)

Other recent books on this domain of experience include my own books, The Art of Losing Control, and Breaking Open Finding A Way Through Spiritual Emergency (co-edited with Tim Read); and Stealing Fire, by Jamie Wheal and Steven Kotler. Also check out the Emergent Phenomenology Research Consortium, which gathers together researchers studying this domain of experience. Finally, here is a shareable graphic for the ten principles.