The literary epiphany as precursor of the New Age

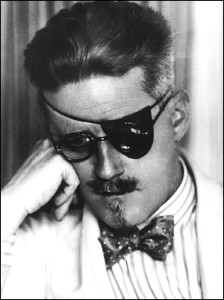

100 years ago this year, James Joyce published Dubliners, his first book, in which he explored the lives of characters through what he called ‘epiphanies’. He’d been experimenting with epiphanies for some years, and even started to write a ‘book of epiphanies’, which he intended - with customary modesty - to send to every library in the world. You can read some of them here.

Epiphanies were, for Joyce the lapsed Catholic, a way to retain a sense of the sacerdotal in everyday life, while still throwing off the ponderous moralisms and barbarous superstitions of the Catholic Church. And many other writers and readers have found in the epiphany a way to retain a sense of spirituality beyond any institution or dogma. In that sense, the literary epiphany is a precursor of the ‘Spiritual but not Religious’ movement of today. And I think it reveals some of the limits of that movement.

The word epiphany comes from the Greek epi-phanein, meaning ‘to show forth, or manifest’. In Christian theology it usually means a revelation of God - in western churches, the Feast of Epiphany celebrates the recognition of Jesus by the Three Magi, while in the orthodox church, Epiphany refers to the moment St John baptises Jesus and the Holy Spirit comes down and anoints him.

Joyce was particularly influenced by the ideas of Thomas Aquinas, the 12th century philosopher, who described epiphanies as moments of realization, where you see a thing’s claritas (radiance), and its quidditas (whatness). The artist, like the mystic, sees something, hears something, tastes something, and is suddenly struck by its incredible luminous quidditas.

This can happen sometimes when you’re on magic mushrooms or LSD - you become completely transfixed by a packet of crisps, by their incredible crispiness. Or you may suddenly see a mate of yours, Jimmy, and be almost overwhelmed by their extraordinary Jimminess.

However, because we’re not being artists, we would struggle to communicate this sudden epiphany to other people. It would just sound weird. The artist, by contrast, has the ability to describe the thing in all its quidditas and to help us achieve a mini-epiphany too. They can capture the epiphany in language, like a lepidopterist capturing a butterfly.

A famous example is Gerard Manly Hopkins’ vision of a windhover:

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king

-dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird,—the achieve of; the mastery of the thing!

An epiphany is not necessarily positive or spiritual - especially not in Joyce. It might be a moment where a person suddenly has an insight into the fatuity and wretchedness of their condition, like a flash of lightening suddenly illuminating how lost you are. This is the negative epiphany, in the sense meant by William Burroughs when he described the phrase ‘naked lunch’ as ‘a frozen moment when everyone sees what’s at the end of their fork’.

Or an epiphany might be a moment where a poor unsuspecting stooge in the street accidentally reveals their true character to the piercing, pitiless eye of the artist. The author and theatre critic Henry Hitchings occasionally posts these sorts of epiphanies on his Facebook page. For example:

Overheard, Shoreditch: "Do I look contained? Man's gotta look contained if he wants to find sweet connections." Somehow I'd take this more seriously if the speaker wasn't carrying a golf umbrella.

or

Brick Lane. The first thing I hear is 'Yo, Django, is the Moog at your place or Fabrice's?'

Wordsworth and the Romantic epiphany

But literature of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries is also replete with more positive epiphanies, in which the artist is struck by something, and seems to see in it a ‘point of intersection of the timeless with time’ (as TS Eliot put it). A thing catches the light, and suddenly seems a window to eternity.

That thing might be a wild flower, as it was for Blake, or a cat, as it was for Christopher Smart, or a couple walking down the street laughing, as it was for Marilynne Robinson.

Yesterday I read some of a book called The Poetics of Epiphany: nineteenth century origins of modern literary moment, by Ashton Nichols, which suggests the key influence on the literary epiphanies of modernism was Wordsworth. He tried in his poetry to capture what he called ‘spots of time’:

There are in our existence spots of time

Which with distinct preeminence retain

A fructifying virtue, whence, depressed

By trivial occupations and the round

Of ordinary intercourse, our minds -

Especially the imaginative power -

Are nourished and invisibly repaired;

Such moments chiefly seem to have their date

In our first childhood

The revolution of Wordsworth’s poetry was to find epiphanies and spiritual revelations not in the typical epic subject matter of Greek myths or the Bible, but in the everyday objects and encounters of his neighbourhood. The most ordinary and common thing - a cliff, a tree, a leech-gatherer - becomes illuminated and holy when it strikes against his consciousness.

Wordsworth then tried, in The Prelude, to make an epic poem of his spiritual autobiography, by weaving together these epiphanies, like a rosary stringing together prayer beads.

This would inspire 19th and 20th century novelists to try and use the novel as a way of exploring the spiritual history of their characters, and how the kairos of their consciousness intersected with the chronos of history. Tolstoy’s War and Peace, for example, explores both the grand sweep of the Napoleonic Wars, and also the spiritual history of Prince Bolkonsky - his moments of epiphany when wounded on the battlefields of Austerlitz and Borodino, when he looks on the infinite sky or feels the flower of ecstatic pity unfolding within him (Bolkonsky is constantly having epiphanies when wounded - he sounds a most impractical soldier).

Both DH Lawrence and Virginia Woolf also tried to make the novel an exploration of the foldings and unfoldings of consciousness. This is what DH Lawrence explores so beautifully in The Rainbow - the struggles of the souls of Tom, Lydia, Will, Anna and Ursula to come into being, to unfold into fullness, and their struggles with each other, how friendships and sexual relationships can either help our unfolding or prevent it.

Sometimes the novelistic epiphany involves a sudden sense of a hidden pattern behind the characters' history - they run into an old love (as in Dr Zhivago) or an old enemy (as Bolkonsky does in War and Peace) and think - why them? Why now? Is this a coincidence or evidence that our lives are somehow weaved together, like works of art, if we could but glimpse the hidden pattern?

The epiphany as narcissistic self-glorification

Now here’s the key point. The literary epiphany was in some senses an evolution of a religious idea or experience in a post-religious age. But the epiphany in Wordsworth and his descendants is quite different to religious experiences in, say, Augustine, John Bunyan or John Wesley.

As Ashton Nichols explores, in religious epiphanies, the experience is very much tied to an theological explanation - it is a revealing of God and the nature of God. The theology is the trellis for the flower of the experience.

In the Romantic and modernist epiphany, by contrast, ‘the powerful perceptual experience becomes primary and self-sustaining. Interpretation of the event may be important but it is always subject to an indefiniteness that does not characterize the powerful moment itself’, in the words of Ashton Nichols. He goes on: ‘the visible reveals something invisible but the status of the invisible component is left unstated. Its mystery becomes part of the value of the experience.’

So theology is abandoned and there is the raw experience, the raw emotion, and the encounter with...something, we can’t be sure what. Call it God, or the World-Soul, or perhaps some private deity of one’s own imagining (Blake’s Albion, Graves’ White Goddess, Allan Moore’s Glycon, Philip K. Dick’s Valis).

In fact, one could say that what is revealed in the moment is not God, but rather the God-like mind of the artist. Wordsworth wrote: ‘To my soul I say / I recognize thy glory.’ Shelley said of Wordsworth: ‘Yet his was individual Mind / And new created all he saw.’ There’s a kind of grand narcissism to the Romantic epiphany - it reveals not the greatness of God but the greatness of the poetic imagination. The poet becomes the Creator, the Animator, and all they see in nature is their own beautiful reflection. Where Milton tells the epic narrative of the human race, Wordsworth sings only the Infinite Me.

This narcissism, this pride, goes back perhaps to Petrarch, and beyond that to Gnosticism. Petrarch wrote that he had learnt from the ancient philosophers that ‘nothing is great but the soul, which, when great itself, finds nothing great outside itself.’ Well...how nice for you Petrarch.

This, I think, is the risk of the modern epiphany. Firstly, there is little sense of how to achieve them through practice, prayer and discipline - the Romantic poet scorns all such discipline as deadening routine. Instead they wander around, perhaps on drugs, hoping for the moment to strike.

Secondly, there is little sense that such experiences are only valuable if they genuinely transform you and make you a better and more loving person. They become an end in itself, which culminates in Walter Pater’s dandyish aestheticism. The poet may be a complete bastard, as long as they have the occasional exquisite epiphany.

Thirdly, there is no sense of beliefs and theology as the trellis around which religious experiences become structured. The experience becomes paramount - and the poet may well hang any old theoretical nonsense around that experience. It leads ultimately to the incoherence and banality of much modern spirituality (one thinks of Paulo Coelho and The Celestine Prophecy, and their deification of coincidences as revelations).

Finally, such moments become excuses not to glorify God, but to glorify one’s Self, one’s own incredible Mind. This is the Gnostic tendency - I am God, I am the Over-Soul, I am the Creator of Heaven and Earth - which one finds in Romanticism, in Wordsworth, Coleridge, Whitman, Emerson and Nietzsche, and which blossoms in the New Age movement of today. This is a dangerous error, because it can become a puffed-up egotism which actually cuts us off from God.

We have forgotten how to pray, how to create routines, habits and practices to carry us through the dry spells and to integrate the epiphanies. And we have forgotten how to kneel.