The mystic’s guide to investment

Maren Altman, who has 150,000 YouTube followers for her crypto astrology channel.

As we’ve explored in previous newsletters, New Age culture has had something of a shocker during the pandemic. It has, in the words of Jamie Wheal, turned into a ‘rat’s nest shitshow’. While preaching health and wellness, spiritual influencers have promoted anti-vaccine, anti-mask, anti-lockdown disinformation and woo-woo alternative cures, just as the United States’ COVID body-count nears a new peak. New Age culture has blood on its hands.

The wave of New Age bullshit has provoked a backlash within spiritual culture, a Reformation, a fight for its soul, with an opposing movement of what I’ve called ‘critical spirituality’. Podcasts and influencers like Decoding the Gurus, Conspirituality and Embrace the Void have won a lot of followers by calling out the bullshit and holding wellness influencers to account. We’ve also seen a slew of popular documentaries exposing abusive gurus — like Wild Wild Country, John of God and the Vow.

But it’s clear to me that skepticism and debunking, while an important activity, is not enough. It’s a good purgative when things are blocked with bullshit, but man cannot live on laxatives alone. We need more solid, nutritious and fortifying fare to live by.

That’s why I’ve long been interested in trying to develop a critical spirituality that balances the Socratic with the ecstatic, the mystical and the critical, enthusiasm with scepticism, bullishness with bearishness. But what does ‘critical spirituality’ practically mean.

The easiest part of ‘critical spirituality’, really, is spotting bullshit in others. It’s much harder to hold oneself to account and spot one’s own biases. The problem is, everyone thinks they’re practicing critical thinking. Everyone thinks they’re the reasonable, evidence-based one and the other side are ignorant fools. You can’t just say to anti-vaxxers or conspiracy-theorists ‘practice critical thinking’ — they’ll say exactly the same to you! ‘Do your research’, they will say.

Above, both vaxxers and anti-vaxxers think they’re standing up for ‘critical thinking’

We all fall prey to ‘motivated reasoning’ — we arrive at a position, often for tribal or emotional causes, and then we find the reasons and logic that support our position. How rare it is for someone to admit they’re wrong or to change their mind.

On the discernment of spirits

At the heart of our search for an intelligent, critical spirituality is the question of the relationship between intuition and analytical reason, between mysticism and logic, between revelation and reason, between, if you like, the Enlightenment and the Romantic Counter-Enlightenment (out of which the New Age grew).

We have different ways of knowing, different forms of thinking, different forms of evidence, and we have to try and weigh them up. If you rely too much on any one method or theory, you will end up with a one-sided model of reality.

Not knocking Jung, just thought this was funny

This debate between mysticism and rationality is very old. There is a long debate in Judeo-Christian culture about how to practice ‘discernment’. It means the ability to discern the will of God, the voice of God, amid all the confusing noise of life.

A message from the Lord might be our imagination (I remember one man at the church I attended telling a gorgeous woman ‘God told me we should be together’). Worse, it might be the Devil, or an evil spirit. St Paul says the Devil sometimes appears as an Angel of Light. The Devil even fooled Mohammad and inserted some ‘Satanic verses’ into the Quran.

In the Middle Ages and Reformation, more and more people claimed ecstatic experiences — particularly lay-women or so-called ‘Piazza Prophetesses’ (I love that phrase). Sometimes these lay-prophets claimed this king or that pope were the Anti-Christ, inspiring violent uprisings. There are parallels with our own confused, apocalyptic time and the spread of ecstatic conspiracy cults like Qanon.

Church theologians tried to develop rules for ‘discernment’. For example, Jean Gerson, 15th-century chancellor of the University of Paris, wrote a series of discernment manuals, in which he suggested we should be like careful investors, testing a product before we buy it: ‘With skill and care we examine the precious and unfamiliar coin of divine revelation, in order to find out whether demons, who strive to corrupt and counterfeit any divine and good coin, smuggle in a false and base coin instead of the true and legitimate one’.

But that’s not easy. Gerson — like subsequent theologians — takes quite a misogynist and classist approach. If a prophet is a woman, she’s likely to be phony or demonic, because a woman’s ‘enthusiasm’ is ‘extravagant, changeable, uninhibited, and therefore not to be considered trustworthy’. Whether a mystic revelation was taken as legitimate or mad / demonic also depended on a person’s class and status, according to medieval historian Moshe Sluhovsky. A person with good connections was less likely to be condemned. (Check out Sluhovsky’s great book on this topic).

All of this reminds me of the contemporary debate over ecstatic / psychotic experiences. Are you suffering from a pathological brain disease, or experiencing a ‘spiritual emergency’? To some extent, it depends on your gender, ethnicity, class and education.

Discernment was not easy, then, back in the Middle Ages. It’s still not easy today. We haven’t got that much further than the theory of 18th-century theologian Jonathan Edwards, who suggested the best test of the validity of a spiritual experience is its fruits — does the experience lead to a better life?

Better how? Richer? Happier? Healthier? Surely these earthly rewards aren’t the proper test, although one often meets that idea in the New Age today. We mean ‘better’ in the sense of closer to God, or closer to ultimate reality. But in that case there is a circularity — the best test of whether an experience comes from God is whether it brings you closer to God. There is a foggy circularity about this path.

Perhaps we could say instead…the test of a spiritual experience, and indeed of a spiritual path, is whether it makes you stronger in wisdom, in virtues like equanimity, patience, kindness, courage and perseverance. Otherwise it’s just an experience, a thrill, a holiday.

A mystic’s guide to investment

I’ll keep exploring this question next week, hopefully with an interview with anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann, who has studied how believers practice discernment. But let me end this week by going back to Jean Gerson’s suggestion that being a good spiritual seeker is like being a good investor.

A good investor does not deal in black-and-white absolutes, they deal in probabilities, they don’t let their emotions guide their decisions, they always re-examine their investments in the light of new information, and they are prepared to let go of decisions which prove to be wrong.

I’m struck by how often modern ecstatic movements overlap with pyramid schemes and financial scams. As Mike Rothschild chronicled in his book on Qanon, Into the Storm, Qanon shared aspects of previous ecstatic-financial fraud schemes like Omega, NESARA and the weird Iraqi dinari scam of the early Noughties. They all promised a massive pay-off — both spiritual and financial — which only the privileged insiders would know about and profit from.

Conspiracy theorists and ecstatic cult believers are bad investors. They’re bad at probabilistic reasoning. This sort of reasoning doesn’t deal in rigid True / False categories, but rather in probabilities. We can use this sort of reasoning when we’re interpreting our mystical experiences, or our hunches, and wondering what to make of them.

For example, as I discussed a few newsletters back, I had a weird near-death experience 20 years ago, which gave me some information: first, my emotional suffering was caused by my beliefs, and second, there’s something in us that never dies, a treasure within, which is from God.

I could test out Belief 1 rationally and experientially, in my life, and it proved to be experientially true and in line with a lot of experimental results from Cognitive Therapy. Belief 2? I can’t rationally or experimentally test it out. But I can live as if it is true. I know it might not be, because rationally I can’t really comprehend it. But I have a 70–80% faith it is true. And if it isn’t? Well, that’s OK, I just die. In the meantime, my speculative bet on the existence of God and the immortality of our souls doesn’t harm anyone, and emotionally helps me.

This may sound a very cautious mode of faith, hedging one’s bets rather than 100% betting one’s life for the divine. But I suggest that is how ‘believers’ really operate — with multiple competing possibilities, multiple ontologies, which shift throughout time. We’re all feeling our way.

What about astrology? I’ve believed in it (this is between us now) for over 20 years, particularly in confusing times. But I increasingly feel this is a poor investment of my attention and belief. No astrologer is able to explain to me exactly how planets exert their influence. And the characteristics of planets seem to be made up.

For example, my astrology app makes much of the transits of Chiron, the ‘wounded healer’. The tiny comet / planet called Chiron supposedly has the character of the centaur Chiron, a healer who himself died of poisoning. Astrologers weave all kinds of stories about how Chiron’s movements cause big healing crises in one’s life. But the planet / comet was only discovered in 1977, by astronomer Charles Kowal, who gave it the name ‘Chiron’ because of its galloping-like motion. It was a pretty arbitrary decision, yet from this name, reams of astrological predictions have been scribbled. Life decisions have been made based on this arbitrary naming! And that’s just as true of the other planets — Mars is Mars because it’s red. Jupiter is Jovial Jupiter because it’s big. It’s time to cut my losses and admit astrology is a poor use of my time, attention and belief. Even so, I still find myself quietly checking the app when I’m bored. Old habits die hard.

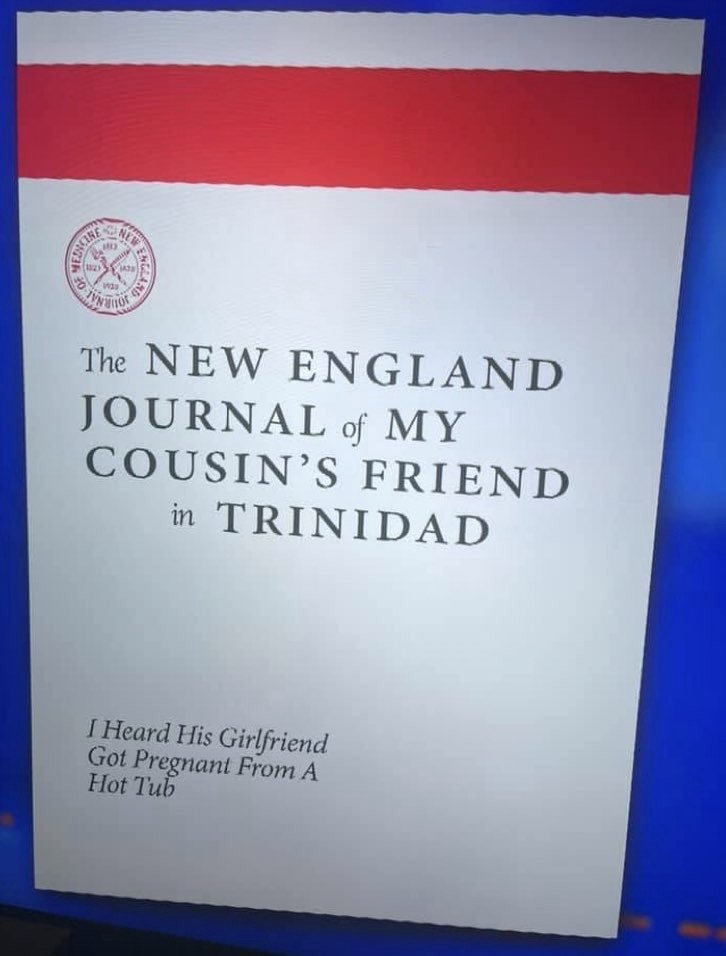

How about vaccines and COVID? Again, we need to deal in probabilities, not rigid absolutes. There is a very small possibility a vaccine could harm us. We have to weigh that against the somewhat bigger possibility COVID could harm us, or the bigger possibility that we could get COVID and pass it on to someone vulnerable, thereby seriously harming others. We should be wary of emotional reasoning like ‘vaccines feel unnatural’, or anecdotal reasoning like ‘Nicki Minaj’s cousin’s friend in Trinidad got the vaccine and his balls swelled up’.

Above, headline of the week from the NY Intelligencer, and a meme comparing peer-reviewed scientific journals to Nicki Minaj’s opinion

If we start to think there is some sort of global conspiracy to hide the side effects of vaccines while exaggerating COVID deaths, in order to exert totalitarian control over world populations, we need to exercise probabilistic reasoning. How probable is it that thousands and thousands of doctors, in countries all over the world, would conspire together in such a grand lie? What if you’re wrong? Some people are so invested in their beliefs, they would rather be dead certain than alive and in doubt.

Or let’s take the Qanon conspiracy. There are some data points that seem to support belief A, that the online poster ‘Q’ knew or guessed what president Trump was going to say or do. A couple of times, Q seemed to guess right. From that you could invest in belief B — ‘Q is who they say they are — a Deep State mole with privileged information’ and then go one further and invest in belief C — ‘The Storm is Coming, there is about to be a total transformation of the global system, from darkness into light’. That is an extremely big leap from A to C, and a huge decline in probability, from occasionally guessing what Trump was going to say to the sudden cosmic triumph of Good over Evil. If you really commit to that belief, if you heavily invest in it to the point of potentially ruining your life, then you are betting everything on extremely long odds. You are very likely to get burned.

Hunches can play a role in investment decisions, just as intuition, dreams, coincidences and mystical experiences can play a role in the spiritual life. They can sometimes give us subtle pointers. But they are rather unreliable sources of information, sometimes marvellous, sometimes rubbish. If you overly or exclusively rely on them for your life decisions, you’re like someone betting their life savings on a fortune cookie.