When politicians lose it

The media and the Labour party have made a lot of noise in the last few days about David Cameron's 'anger problem', after he called Shadow chancellor Ed Balls a 'muttering idiot' in Prime Minister's Questions. Balls is extremely good at getting under Cameron's skin, and this time he was telling the PM to 'have another glass of wine' - a reference to a recent story that Cameron likes to 'chillax' at the weekend with several glasses of wine while playing 'fruit ninja' on his iPad (the implication being he is a bit too chillaxed for the country's good at a time of deep economic crisis).

No sooner had Balls successfully provoked him, than the Labour spin machine went into action, questioning Cameron for not being relaxed enough, having an anger management problem, and generally being a bit of a bully (which is rich coming from Ed Balls).

The game Labour is playing is an old one: question the capacity of a rival to govern a country by questioning their capacity to govern themselves. Think how many political leaders have lost authority and power because of their inability to govern themselves: there are the sexually indisciplined, like Bill Clinton, David Profumo or (more extremely) Dominique Strauss-Kahn; the alcoholically indisciplined, like Boris Yeltsin; and those who's distrusting and wrathful temperaments also harmed them, such as Gordon Brown or Richard Nixon. And then there are those leaders who simply went completely round the bend, like George III.

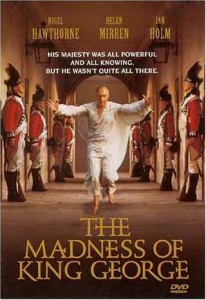

Alan Bennett's play, The Madness of King George III, shows what happens when a king loses the ability to govern himself - he very rapidly loses the chance to govern his country. In a smaller way, The King's Speech is also about the connection between a ruler's ability to govern himself (and in this case, his speech impediment) and his right to govern others.

The same is true in corporations: the CEO needs to be able to govern themselves well, especially in public situations like results presentations, in order to win the confidence of the public markets. Enron's problems were deep-rooted, but the company really got into trouble when CEO Jeff Skilling called an analyst an 'ass-hole' during an investors' conference call. It was a shocking indication of lack of self-government, and sent the company's stock price into a free-fall.

Yet rulers are in a difficult position: if they govern themselves too successfully and control their emotions too completely, they can be accused of being distant, cold, heartless. And so the good ruler must not only manage their emotions, but stage-manage them, producing public displays of emotion when needed - Hillary Clinton is a prime example. In the 2008 Democratic primaries, she was accused of being unfeeling. The next press conference, she produced a tear with all the flourish of a chicken producing an egg.

On the whole, then, the better a ruler is seen to govern themselves, the greater authority they have over others. This, so the English told themselves, was the secret to their imperial dominion over the rest of the world: it wasn't just their guns and steel. It was their Stoic ability to control their emotions better than any other tribe - such is the myth the English upper classes told themselves, I don't comment on its truthfulness. It was also a myth the Romans told themselves. Imperial powers often justify their right to govern other people against their will by claiming the other people are effectively children, who lack the capacity to govern themselves, who are lazy or irrational or over-passionate, and therefore need to be governed by wiser rulers.

Yet note how the most successful revolutions of the colonised against empires are often led by charismatic leaders who lead partly through their astonishing ability to control themselves, and to maintain a calm dignity under the most difficult situations: think of Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, or Martin Luther King. Gandhi, for example, was a champion of self-governance or 'Swaraj', which for him meant both the right of Indians to govern themselves, and the capacity of Indians to govern themselves in their personal lives, as he did with his incredibly self-demanding ascetic regime. He said: "At the individual level Swaraj is vitally connected with the capacity for dispassionate self-assessment, ceaseless self-purification and growing self-reliance".

I can think, however, of at least one ruler who has adopted a very different strategy: Vincent Gigante, a Mafia don in New York who for three decades avoided imprisonment and carried on running his crime family by pretending to be mad, even wandering around New York in his dressing gown and pajamas. He earned himself the nick-name, 'the Odd-father'. All that time, he ran his crime empire via the handful of close associates who knew he was putting on an act. Now that takes real self-control.