2013 round-up: well that was a weird year

Well, that was a weird year. 2013 was the year I became a Christian, or rather 'committed my life to Christ' as Christians put it. What does that mean? How did I get here? Am I really a Christian or am I kidding myself? Let's re-wind and play the tape again.

I ended Philosophy for Life with an appendix called ‘Socrates and Dionysus’, in which I suggested there is an alternate way of approaching life to Socratic philosophy, which is less about self-knowledge and self-control, and more about losing control and opening yourself to what I called ‘the wilder gods of our nature’. I felt that Stoicism, while an enormously helpful philosophy, is perhaps too rationalistic, that it misses out some important parts of life, like music, poetry, dance, the imagination, grace - in a word, the ecstatic.

Why was I interested in the ecstatic? Partly because I love the arts, and partly because I’d been profoundly healed by a weird sort of near-death experience which happened to me back in 2001, which I wrote about at the end of last year. I felt that was an encounter with...Something Else....and it was Good and Love...and I felt a debt to Him / Her / It / Them for having saved me, when I was lost in suffering.

The Mountain Moment ™ gave me the insight that, often, it's our thoughts which cause us suffering and our thoughts which hold the key to liberation from suffering (I know, not a very profound insight, but it was helpful at the time!), an idea I tried to communicate in my book and talks. But now, a year after the book came out, I wondered...what was that experience? Have others had similar experiences? What are we to make of them? Like William James, I was interested in the fact that such ecstatic moments are often very healing, yet we have no real place for them in our atomist-materialist culture. Indeed, we sometimes pathologise such encounters with the Numinous as psychotic delusions - something I wrote about last year in an article in Wired.

More than this, I was interested in whether there really is a God, and if so, how we should live in accordance with His / Her will. Are ecstatic moments a window beyond the paradigm of materialism, a way to connect with God, or are they just nice feelings? Is there a way, as Rudolph Otto hoped, that we can find a balance between our non-rational experiences of ecstasy and the more rational aspects of human thought?

I had also become interested in the role of the ecstatic / sacred in creating and cementing communities - something Emile Durkheim famously explored. I’d spent the second half of 2012 researching philosophy clubs, and come away with a sense of their limits. I felt communities based on rational inquiry were probably weaker than communities based on love and self-sacrifice - a belief influenced by my meeting Tobias Jones in December 2012 (you can listen to our conversation in this Aeon podcast, from 28 minutes in). I was hungry for deeper community than I could find in philosophy clubs.

In December 2012, I was dating a Christian girl, and I met some of her friends, and was impressed with their sense of community, how they listened to each other and honoured each other. One of them was a curate at Holy Trinity Brompton, where he was in charge of the Alpha course. So, in January, I decided to do the Alpha course.

I really enjoyed it - particularly the communal aspect of it, although I have to say the theology of the course didn’t really persuade me. The course begins with CS Lewis’ contention that either Jesus was the Only Son of God, as he claimed to be, or he was a liar or lunatic. In fact, as Anthony Kenny recently pointed out in a review of a new biography of Lewis, ‘even most conservative biblical scholars today think it unlikely that Jesus in his lifetime made any explicit claim to divinity’.

The Alpha course also makes a lot of the belief that Jesus died for us to pay the debt incurred by Adam’s fall. But does that mean that to be a Christian, to understand the extent of Christ's sacrifice, I have to believe in Original Sin? I find that idea far less convincing than the evolutionary alternative - that our violent, flawed and stupid nature comes not from some poisoned apple, but from our animal origins (although this raises the question of how we developed any capacity to transcend our flawed nature, and whether that capacity is God-given. I think it is.).

The Alpha course is great on the Holy Spirit, on God’s love, and gives spiritually-starved westerners some sense of that love. But - as in a lot of charismatic Christianity - the shadow of that faith in God’s love is a strong belief in the Devil’s power. I met various Christians over the course of the year who believed every other spiritual tradition, with the possible exception of Judaism, is demonic, that secularism is demonic, that everything except their particular culture is demonic. Even other bits of the church are demonic...perhaps even other bits of their congregation are demonic. This is not a broad, generous and expansive vision of human existence - it's narrow, fearful, suspicious. It is a worldview that implies God is content to let most of his children go to Hell (and why not - He killed off 99.9% of creation before, in the Flood).

So, by about April or May, I’d made an initial attempt to find a place in Christianity, but found myself repelled by aspects of its theology. I was still interested, however, in humans’ desire for the ecstatic. I became very interested in the cultural and spiritual role of pop music, in how pop music emerged from Pentecostal and Baptist churches in the 1940s and 50s and was a form of secularized ecstasy - a point made brilliantly in a book called Sweet Soul Music by Peter Guralnick, one of my favourite books of the year.

I also loved Altered State: The Story of Ecstasy and Acid House Culture by Matthew Collin, and wrote about acid house as an ecstatic popular movement. I interviewed my old landlady, Sister Bliss from the group Faithless, about how rave music was a sort of church for the unchurched. I also interviewed Brian Eno, producer of some of pop’s great ecstatic anthems, about his theory of how we seek the experience of surrender through religion, drugs, sex and music. And I interviewed Imperial's Robin Carhart-Harris about his research into psychedelics as a healing therapy.

By spring-time, I was wondering how to organize and communalize this interest in ecstatic worship (after all, even if I couldn’t accept Christian theology, I still believed in God and wanted to worship Him / Her with other people). At one point I even considered starting my own non-conformist church, which would bring together philosophy and gospel music! Then I saw that a new humanist church called the Sunday Assembly was looking for a drummer for their house band. So I signed up, and played in a couple of their services. It interested me as an attempt to create a more ecstatic humanism - but ultimately it didn’t have enough spirit for me.

I was then ill for the whole of May, and feared I might have chronic fatigue syndrome or something like it - in fact I was diagnosed last month with a genetic blood defect called haemochromatosis, which leads to very high iron levels and a weak immune system. It's known as the Celtic Curse, because it mainly affects Celts, and is treated by a somewhat medieval treatment involving weekly blood-lettings! But I didn’t know what it was back then, and that month in bed, feeling like a ring-wraith, coincided with a sort of spiritual doldrums. Where was I to go? What was I to do?

I went to a Christian folk concert in May, and sat surrounded by passionate and chirpy young Christians, and said to a Christian friend of mine: ‘I could never be a part of this’. He told me about a Christian retreat in Wales called Ffald-Y-Brenin, supposedly a ‘thin place’ - a place where the Kingdom is close. I read a book called The Grace Outpouring, by the guy who runs it, Roy Godwin. I was also, at that time, researching the Welsh revival of 1904, when a wave of Pentecostal fervor swept through Wales. All that reading about Welsh ecstasy perhaps primed me for what happened next.

In mid-June, I drove down to Ffald-Y-Brenin, to their summer conference, spending three days in a church filled with ecstatic pensioners. For the first day and a half I wondered what in hell I was doing there. Then, on the final afternoon of the conference, I visited the retreat, this supposedly 'thin place' , and I guess it had affected me somehow, because in the evening service, I found myself quietly dedicating my life to God - just quietly committing whatever gifts or talents I had to God. And then I felt this force blowing into me, filling my chest, pushing my head back, a sort of painful joy which took my breath away. It lasted for, I don't know, twenty minutes or so.

Right after it happened, Roy Godwin asked if anyone in the church wanted to commit their life to Jesus. Which was strange, because everyone in the church, except for me, was already a committed Christian, and I don’t think he could see me, having a moment at the back of the church balcony. So, I don’t know if he had spiritual insight or what. He said, ‘you don’t need to come forward, just raise your hand, no one will see’ - we all had our eyes shut. So I raised my hand. Cripes, I’d gone and committed my life to Jesus!

At the end of the conference, I bounced up to Roy Godwin to thank him (having not spoken to him before or said who I was). He turned to me immediately and said: ‘Sure. Listen, don’t be offended but God says you can stand on the outside analysing, but He is here, waiting for you’. Which struck me as an interesting thing to say, considering I’d spent the year academically researching ecstatic experiences.

Was I rationally persuaded of all the main points of Christian theology? No. I still don't know what the afterlife holds, or what the future of the multi-verse is. This was a non-rational encounter with a spiritual force which I took (and still take) to be good. Perhaps it also came from within me...perhaps it emerged from a deep psychological need in me for there to be a transcendent meaning to life (although it felt more powerful, somatic and involuntary than that). Some people don’t feel that need: I do. I think our culture desperately needs a window to open to the transcendent.

The West seems to be losing itself in triviality, which we cover up by calling everything ‘awesome’. New iPhone? Awesome. YouTube video of a dancing cat? Awesome. The words of the year, according to the OED and Collins dictionaries, are geek, twerk, binge-watch, selfie and onesie. We’re a dying culture, an autistic culture, taking refuge in gadgetry and infantilism. We’re heading for environmental death and, like Theoden in The Two Towers, we don’t have the spiritual strength to face it.

I became more and more convinced of the limitations of scientific materialism. I read Max Weber, and agreed with his account of our society’s disenchantment, but felt that his vision of scientific rationalistic bureaucracy was deeply unappealing - even to him! Mechanistic materialism, I argued in August, failed on the 'three Cs': community, creativity and consciousness.

I found William James much more sympathetic, and his Varieties of Religious Experiencehas been a key influence on me this year. I admired his attempt to bring together the rational-empirical and the sacred-numinous, and his attempt (like Jung) to find a new and positive language for such experiences in psychology. His work led me to a rich contemporary literature on ‘the science of religious experience’, including work by American religious scholars like Ann Taves, Tanya Luhrmann and Jeffrey Kripal, who all happened to come together at Esalen in California in October for a conference on the paranormal.

Kripal, who I met at a conference on altered states of consciousness at Queen Mary last month, is a particularly challenging thinker for me, because he points out that spiritual experiences happen to many people, in many religious traditions and outside of any religious tradition. We need to be open, he thinks, to the marvelous and fantastic aspects of such experience, without trying to shoe-horn them into either a fundamentalist religious interpretation or a scientific materialist interpretation. They are weirder than that. OK, I said to him. But what do we do with that? How do we know what's out there and whether it's benevolent? How should we live?

While I like Kripal's skeptical paranormality, and share his interest in superhero comics as an ecstatic art-form, for me, traditional religion seems a decent working hypothesis about the spiritual realm and how to live in relation to it - as long as one doesn't become a self-righteous fanatic. 'Organized religion' is such a pejorative term now, but the alternative is a completely individualised relationship to the Divine without any real community or collective myths and rituals.

Meanwhile, in October, I joined up with the RSA in a project of theirs to discover a scientifically credible form of spirituality, one which doesn’t demand a metaphysical leap into the dark. The project is organized by Jonathan Rowson, and has enabled me to learn from some fascinating thinkers about spirituality and the ecstatic, including the psychologist Guy Claxton (here’s a talk he gave last month on spiritual experiences) and the psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist. The latter’s magnum opus, The Master and the Emissary, was one of the most interesting books I read this year - it suggests that the split between rationality and the imagination is, in fact, neurologically-determined. The left hemisphere of the brain is more prone to rational, abstract and conceptual thinking, he argues, while the right hemisphere is more intuitive, holistic and imaginative. McGilchrist argues that western culture has become more and more dominated by the left brain’s view-point, and ever-more deaf to the right-brain’s alternate world-view. OK then, what is to be done?

McGilchrist suggests we can perhaps find liberation from the tyranny of the left-brain through the body, through the arts, and through the spirit. I have come to a similar conclusion (although I leave the hemispherical neurology to him). The arts are one way we can still go beyond the rationalistic and access the Sublime or Ecstatic, although like McGilchrist I worry that we’re becoming more and more deaf to this alternate world-view. I wrote about art as an ecstatic transporter here, and this month I interviewed a wonderful poet-priest, Malcolm Guite, on poetry as a ‘door into the dark’. I also became interested in horror as the opposite of the Ecstatic (ie you encounter a spiritual presence, and it’s evil), and I wrote a piece on Kubrick’s The Shining as a tour-de-force in the Uncanny.

I’m increasingly interested in artistic inspiration as an ecstatic experience, and in how gifted people can tap into alternate voices or what James would call alternate centres of consciousness in their psyche, and then shape them into art - have a listen to novelist Marilynne Robinson talking about how she hears a voice telling her about her novels here, or Johnny Vegas talking about how he created his comic alter-ego to body forth a voice in his head. Artists, it seems to me, are still doing what shamans used to do - channeling voices in order to connect us to altered realities - although these alternate selves can take over the artist's personality in damaging ways.

I summarized some of this year’s research into the Ecstatic in a talk I gave at the Free Thinking Festival in November.

It has been a strange year, and I still find Christianity rather like an uncomfortable and scratchy jumper, which chafes as much as it warms. I find Christian community likewise both warming and also occasionally alienating. I love many of the Christians who have befriended me this year, but I really don’t know if I can be called a Christian in any orthodox sense, in that I still love and admire other spiritual traditions, and don’t feel I have a very close relationship to Jesus, like many of my female Christian friends seem to do (maybe it’s easier to have a passionate romance with a male deity if you’re a woman?) Prayer still feels strange to me, like talking into a stubborn silence. I still struggle to know the extent to which God cares about human suffering, or why He lets things like the Holocaust happens, and I have yet to hear a convincing Christian answer to 'the problem of suffering'. As I wrote back in June, I've had some experience of personal grace, but such experiences raise the question of why other innocent people are not saved from awful, awful suffering? You could follow Plato and the Buddha and say 'everything evens out in the cycle of reincarnation' - that makes a bit more sense to me.

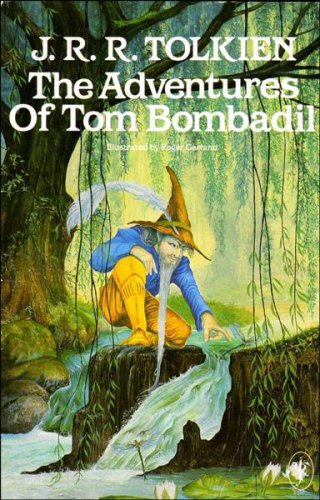

It seems hopeless, sometimes, to ask these metaphysical questions. How am I, with all my cognitive limitations, meant to make out what is going on in the multiverse? I have a keen sense of the limit of our knowledge of what is going on 'out there', and I don't think the simplistic Protestant hypothesis of God versus the Devil adequately explains the sheer mess, joy and suffering of human experience. I think it's more likely there are many spirit-entities / beings of higher intelligence in the multiverse, some of them benevolent, some of them malevolent, some perhaps serenely indifferent to human concerns (like Tom Bombadil!) but all ruled by one Logos, one Energeia, one God. At least, I hope they are. These various entities are (perhaps) hungry for our consciousness, our attention. Some suck it out of us and kill us, others we can engage in a symbiotic loving relationship that enhances and enriches our life and the life of our species.

Well, who knows...I...er...don't have any bar-graphs to prove these speculations.

Looking down here on Earth, and specifically at the Anglican church, I don't have a sense is there is a hugely vibrant tradition of the sort of generous, culturally-open, arts-loving, body-loving, ecstatic Christianity that I admire, a Christianity that is charismatic without being fundamentalist, that believes there is good in many different traditions, including humanism, a Christianity like William Blake or Owen Barfield or Thomas Merton imagined. But there is enough out there to give me hope.

Meanwhile, the old work, of promoting ancient philosophy, has continued with its own momentum this year. At the beginning of the year, I ran a Philosophy for Life course at Queen Mary. I’ve also done philosophy workshops at Saracens rugby club, in libraries and mental health charities, and in Scottish prisons. I’ve done a lot of free talks, including a TEDX talk, and wondered if it’s possible to make a living from street philosophy. In December, I helped to organize Stoic Week, and took part in a big event on Stoicism for modern life, a panel of which you can watch here. I hope next year to do more practical philosophy events in prisons and in schools, and perhaps even to help develop a new curriculum for Religious Education, which includes some practical philosophy in it. Oh, and Philosophy for Life came out in the US, and was picked as a Times book of the year this weekend!

Well, I hope you’ve enjoyed this year’s ecstatic explorations, and that you have a wonderful Christmas and New Year. See you in 2014,

Jules