Bowie's genius versus Eno's scenius

Is there such a thing as 'individual genius' or is it a product of collective socio-cultural circumstances? This article explores two views, associated with David Bowie and Brian Eno.

In the mid-19th century, the grand old sage of Victorian culture, Thomas Carlyle, was worried that Christianity was wearing out, that the West needed a 'new mythus' to bind us together and connect us to the infinite. Carlyle decided that a substitute for the worship of Christ might be the worship of heroes, ‘these great ones; the modellers, patterns, and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain’. He had in mind prophets like Mohammad, poets like Byron and political leaders like Napoleon. Worship of genius would become ‘the final religion’, as Will Durant would put it. Carlyle's vision came true - throughout the 19th and early 20th century, we saw the rise of the cult of the national hero or genius - Napoleon, Garibaldi, Ataturk, Stalin, Hitler, Mao, Putin, and so on.

Then, at the very end of the 19th century, Oscar Wilde adapted Carlyle's idea to create the modern cult of personality, or celebrity. As he wrote in The Picture of Dorian Gray, ‘personalities, not principles, move the age’. Wilde realized you didn’t need to establish a nation or religion to create your own cult of personality. You just needed to be beautiful, witty, fascinating and well-publicized. Where Carlyle saw genius as this deep, spiritual connector to the divine, Wilde suggested a celebrity could be an empty amoral mask - and still be fascinating. ‘It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances’, declares the aesthete Lord Henry. ‘The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.’ Where the Victorian Carlyle strove for sincerity and earnestness, Wilde embraced wit, irony, epigrams, paradox, the play of masks - the only sin is to be ugly or boring. In Wilde’s aesthetic vision, the wit, the dandy, the actress and the supermodel are the creative elite, the new gods, those allowed to live by their own rules and explore every facet of their personality and desires, to realize that ‘man was a being with myriad lives and myriad sensations’. Meanwhile, everyone else - the boring masses - copies the gods, emulates them, not really living their own life at all, they become ‘an echo of someone else’s music’.

Wilde self-consciously established himself, when still in his early twenties, as a new god, a genius, the guiding spirit of his age, the Grand Fascinator, its pre-eminent critic, author, wit, personality and trend-setter. His life would be his greatest work of art. But life-as-performance-art has its risks - when you turn yourself into a work of art, you commodify and objectify yourself. You live and die in the eyes of the public. One senses a deep terror of being exposed, shamed, ostracised and scape-goated in the author of Dorian Gray. The public might not like certain aspects of you, you may have to hide some of yourself which then gets revealed (as Dorian's shadow eventually gets revealed). Or you may find yourself stuck on your pedestal, stuck playing a role, like the Happy Prince. You might be like Sibyl Vane, the actress that Dorian Gray falls in love with, but only when she is performing a part. As soon as she is herself, he dumps her. This situation would play out in real life later, when Wilde’s young lover Bosie wrote to him: ‘when you are not on your pedestal you are not interesting.’ There is a moral anxiety running through Dorian Gray - is life really just a play of appearances and masks? Is there never a moral reckoning with what’s within? The Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard saw this same problem with aestheticism in his book Either / Or, which is a sort of dialogue between an ethicist and an aesthete (between Carlyle and Wilde, if you like). And the ethicist says:

Do you not know that there comes a midnight hour when every one has to throw off his mask? Do you believe that life will always let itself be mocked? Do you think you can slip away a little before midnight in order to avoid this? Or are you not terrified by it?

Wilde was terrified by this midnight hour, and you can see him in his art trying to work out the two sides of his personality - the ethicist and the aesthete, the Platonist and the Sophist, trying to be beautiful and fascinating, but also yearning to be spiritually whole and good. Dorian Gray is a brilliant portrayal of the self-division and corruption of living your life as a work of art, and in his children’s stories you see him trying to evolve, to go beyond being a beautiful mask, to embrace his shadow and become whole and individuated (there are several Beauty and the Beast-type stories where the hero meets and takes pity on a tramp-figure, and this leads to a magical transformation). But Wilde failed to evolve, and ended up condemned by the public - his inner psychodrama played out on the public stage, horribly.

Wilde predicted how British culture would develop after WWII, after the decline of the cult of Christianity and the cult of empire. Britain became what Dominic Sandbrook called the Great British Dream Factory, forging identities and attitudes for the world to gaze at and buy into. Pop culture became a new religion - as John Lennon would say, the Beatles were bigger than Jesus. David Bowie was very conscious of pop as cult - ‘til there was rock you only had God’, he once quipped. He embraced the Wildean idea of life as art, and modelled himself - or Ziggy Stardust - as a Wildean hero, a great man, a genius, a pattern for the masses to follow. He was an advanced being, an alien from the future, a starman, a homo superior, a catalyst, a funky instigator, what Shelley called the ‘legislator of the age’ and Ezra Pound called ‘the antenna of the race’. And, as in Wilde’s vision, the masses are just replicants or zombies. The genius makes a gesture, and the masses copy it like zombies - this is the message of the Fashion video. This cult of personality easily becomes fascistic. At the height of his cocaine-psychosis in 1976, Bowie declared: ‘I’d love to enter politics….I will one day. I’d adore to be Prime Minister. And yes, I believe very strongly in Fascism. The only way we can speed up the sort of liberalism that’s hanging foul in the air at the moment is the progress of a right-wing totally dictatorial tyranny and get it over with as fast as possible’. From the self as art, to society as grand canvas for the genius’ dreams. And so Bowie existed for a while in the midnight hour between Sally Bowles and Hitler. But Bowie was too restless to stay long in his own cult, too inventive, he was constantly excommunicating himself from his own religion. ‘As soon as you’re on safe ground, you’re dead.’ He relentlessly smashed his own idols. Fans turned up to gigs dressed as Ziggy, and he was already on to the next one. He managed to maintain an outsider perspective, throughout his career, and this is part of the secret of his long fecundity. As Jonah Lehrer wrote in Imagine: ‘outsider creativity isn’t a phase of life, it’s a state of mind’.

For eleven years, from 1969 to 1980, Bowie was the white heat powering the Great British Dream Factory, as it pounded out the ch-ch-ch-changes, relentlessly mass-producing new poses, new attitudes, new lifestyles for the youth market. It was an astonishingly creative period - he wrote a classic album every year, each in a markedly different style, each inspiring a whole subculture. It is comparable to Bob Dylan’s creative peak, from 1962 to 1966, or the great creative spurts of geniuses like Coleridge and Wordsworth, or Walt Whitman, when they channel the spirit of the age, before the creative daemon departs as abruptly as it arrived. We recognize it as genius. But what is genius? What is this power that sometimes appears in certain people in certain scenes at certain times? Where does it come from? Where does it go? Is it within, in genes, in the individual’s soul, or without, in their socio-historical circumstances? I’m going to argue it’s both - it’s in the interplay between a genius’ unique psychology, and the unique lucky circumstances of their time.

The Myers-type genius as mediator between the subliminal and the supraliminal

One of the best psychological theories of genius I’ve come across is from Frederic Myers, the great British psychologist who developed what William James considered the most comprehensive theory of the subliminal mind, by which he meant those aspects of the psyche which are beyond ordinary consciousness. Myers defined geniuses as those who are particularly receptive to ‘uprushes’ from the subliminal mind, in the form of flashes of inspiration, insight, vision and epiphany. People like Nietzsche, who wrote: ‘one can hardly reject completely the idea that one is the mere incarnation, or mouthpiece, or medium of some almighty power…One hears - one does not seek; one takes - one does not ask who gives: a thought flashes out like lightning’. Myers speculated the subliminal mind might be particularly associated with the right hemisphere, and there is now some evidence that creative insights are born there, but it’s early days for that theory. In any case, the barrier between the subliminal and the supraliminal is unusually permeable in geniuses, as in psychotics. Their openness to the subliminal explains why geniuses may often be quite nutty, and fall prey to nutty ideas - Newton believing in alchemy and apocalyptic prophecies, Nikola Tesla’s quasi-erotic obsession with pigeons. But rather than being overwhelmed by the contents of the subliminal mind, as a psychotic is, a genius is able to order them into a scientific theory or a work of art, using their supraliminal mind (ie their reason, discernment and will). Geniuses are ‘amphibian’, as Seamus Heaney described the poet Robert Lowell, able to descend into the slimy depths like Orpheus, and come back intact. They may use certain techniques to invoke their subliminal mind - reverie, dreams, visualization, self-hypnosis, meditation, drugs, the occult - or they may simply know when to stop thinking and go for a walk, as Charles Darwin did.

While some contemporary psychologists like Max Nordau and Cesare Lombroso thought geniuses were pathological degenerates, Myers thought geniuses were actually instances of the evolution of homo sapiens. The subliminal mind was, he believed, not just personal but suprapersonal - it extended outwards to other people (he believed in telepathy and clairvoyance), to the dead, and to the past and future. It contained the seeds of the future, and the genius’ hyper-sensitive antennae pick up the frequency and relays it back to their own time, in the form of new ideas, new visions, new worlds. The genius is supernormal - ‘something which transcends existing normality as an advanced stage of evolutionary progress transcends an earlier stage.’

Bowie fits Myers’ definition of genius. Where his half-brother Terry was overwhelmed by the contents of his subconscious, and committed to a mental health facility for schizophrenia, David managed to maintain an uneasy dialogue between his supraliminal mind and the volcano of the subliminal. ‘I’m quite Jungian’, he said in an interview for Uncut magazine in 1999. 'The fine line between the dream state and reality is, at times, quite grey. Combining the two, the place where the two worlds come together, has been important in some of the things I’ve written.’ He was prone to hallucinations, even before the cocaine psychosis of the mid-1970s. The lyric from Oh You Pretty Things (from the 1971 album Hunky Dory) - ‘crack in the sky and a hand reaching down to me’ - described a vision he’d had. He also opened up to the subliminal using techniques like meditation, free association, the occult, Surrealist techniques like cut-ups or Eno’s oblique strategies, sleep deprivation, and long drug-binges. He thought of his waking dreams as prophetic for his era. ‘The idea of having seen the future, of somewhere we’ve already been, keeps coming back to me’. He played out his waking dreams in archetypal figures - Ziggy was, he said, ‘an archetype’, so was the astronaut Major Tom, the alien Thomas Newton, the Pierrot, the thin white duke. They were all aspects of his psyche, his personal psycho-drama. The psychologist Jerome Bruner thought one of the secrets of the creative personality was a willingness to explore the drama between aspects of the self. Bruner wrote in On Knowing: Essays for the Left Hand:

There is within each person his own cast of characters — an ascetic, and perhaps a glutton, a prig, a frightened child, a little man, even an onlooker, sometimes a Renaissance man. The great works of the theater are decompositions of such a cast, the rendering into external drama of the internal one, the conversion of the internal cast into dramatis personae… It is the working out of conflict and coalition within the set of identities that compose the person that one finds the source of many of the richest and most surprising combinations. It is not merely the artist and the writer, but the inventor too who is the beneficiary.

The risk with Bowie’s psychodrama, as with Wilde’s, is that it was played out so very publicly, with the deafening feedback of public adulation. The personae his subliminal self threw out were then taken up and adopted by the adoring masses as identities. So he'd create and put forward one particular persona - Ziggy - and the audience sucked it up, consumed it, and demanded it again. The drug of public adulation, and the money and power-games that come with it, can imprison the artist in one role, which they have to fit into while hiding any parts of their psyche that don't fit that role (Ziggy is brash and confident, but Bowie was more complex than that). Each beautiful mask you put forward creates a shadow, a dark doppleganger, of all that is left out. Bowie says he felt haunted by Ziggy - ‘that fucker wouldn’t leave me alone…I think I put myself very dangerously near the line’. He came so close to self-destruction, so close to losing himself. Yet he managed to let go of each mask and confront and recognize the shadow, as he describes it in the very Jungian song Shadow Man:

Look in his eyes and see your reflection

Look to the stars and see his eyes

He’ll show you tomorrow, he’ll show you the sorrow

Of what you did today

You can call him his foe, you can call him his friend

You should call and see who arrives

For he knows your eyes are drawn to the road ahead

And the shadow man is waiting for you round the bend

Oh the shadow man o o o

It’s really you

Bowie managed, unlike so many rock prophets before him, to ‘keep formation, mid the fall-out saturation’. And that was partly through a spiritual seriousness, behind all the irony and masks. He ultimately put spiritual wholeness higher than the screaming feedback of fame. If you want to hear an artist taking themselves to the very brink of madness and dissolution, and coming through it, listen to Station to Station, made at his very lowest, when he was psychotic on cocaine and obsessed with the occult, conjuring demons who threatened to devour him. And listen particularly to Word on a Wing, where he kneels to God and begs for his help, with seering sincerity and desperation:

In this age of grand illusion, you walked into my life out of my dreams

I don't need another change, still you forced a way into my scheme of things

You say we're growing, growing heart and soul

In this age of grand delusion, you walked into my life out of my dreams

Sweet name, you're born once again for me

Sweet name, you're born once again for me

Oh sweet name, I call you again, you're born once again for me

Just because I believe don't mean I don't think as well

Don't have to question everything in heaven nor hell

Lord I kneel and offer you, my word on a wing

And I'm trying hard to fit among your scheme of things

It's safer than a strange land, but I still care for myself

And I don't stand in my own light

That is the sound of Dr Faustus at the midnight hour, miraculously being saved rather than torn apart. And what you get in Low and Heroes (the albums which followed Station to Station) is a sort of spiritual triumph. I fucking made it through! As he put it: ‘I saw a light at the end of the tunnel, and it wasn’t a train coming.’

But if Bowie had an unusual openness to the subliminal mind, he also managed to shape and steer it with his supraliminal or conscious mind. This is the difference between the genius and the eccentric or psychotic. Bowie had amazing powers of control and discernment in the artistic process, even during Station to Station, ‘a work of precision and focus and exquisitely controlled power’, as the Guardian’s Alexis Petridis wrote this week. He was very open to the unexpected and spontaneous - king of the first take - but he also knew what he didn’t want. He had discernment. The inventor Jacob Rabinow said that if you want to be an original thinker ‘you must have the ability to get rid of the trash which you think of’. Nietzsche agreed: ‘All great artists and thinkers are great workers, indefatigable not only in inventing, but also in rejecting, sifting, transforming, ordering.’

Brian Eno’s Scenius

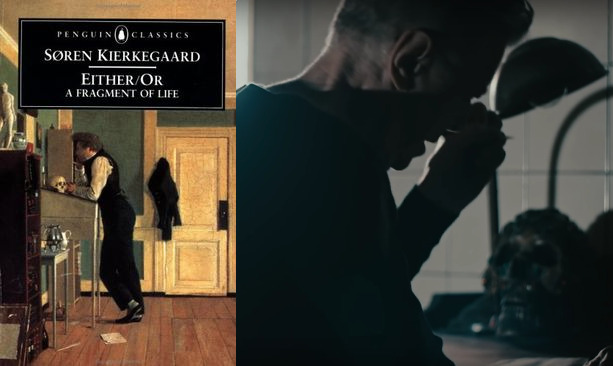

Bowie, then, was a genius of the Myers-type - able to live on that jagged edge between the subliminal and supraliminal. But is this model of genius too individualistic? Are we indulging the Romantic myth of the solitary genius alone in his garrett, like the figure on the cover of Kierkegaard’s Either / Or which Bowie seemed to nod to in his final video for Lazarus? There is another, more collaborative, model of genius, which Bowie’s ‘soul-mate’ Brian Eno has outlined, called 'scenius'. This refers to ‘the talent of the whole community’ - Florence in the Renaissance, British pop culture in the last half-century - when ‘new ideas are articulated by individuals but generated by the whole community’.

Bowie was this kind of ‘scenius’ too. Firstly, he had a sort of sponge-brain, able to soak up and retain impressions and ideas from his environment, as a cloud absorbs moisture until it bursts in lightning. Different cities were important to his creativity as inspirations - New York, LA, Berlin. He absorbed these environments like a fly stuck in milk, as he put it. In this, he was like David Byrne of Talking Heads, who has described cities as his ‘muse’: ‘If you look and listen in a city, then your mind gets expanded automatically’, Byrne says in Lehrer's Imagine.

Sponge-brain Bowie had an amazing memory-bank of ideas. He said:

I’ve always found I’m a collector. And I collect personalities, ideas…Everything I read, every film I saw, every bit of theatre, everything went into my mind as an influence. I’d think ‘that’s going in the memory bank’.

This vast memory-bank enabled him to assemble ideas and impressions, and then bring them together into unusual combinations - sci-fi, Dietrich movies, French chansons, continental philosophy, rhythm and blues, Bertolt Brecht, German techno, the occult, mime, Gnosticism, Japanese theatre. Memory is key to creativity - they knew this in the Middle Ages, when invention was understood to be closely tied to the inventory or storehouse of the memory. Medieval monks and Renaissance magi used memory-training techniques like the ‘mind palace’ as a way of storing information to use for composition. Mozart was also apparently so prodigiously creative partly thanks to his memory. He wrote in a letter: ‘When I proceed to write down my ideas, I take out my bag of memories, if I may use that phrase…For this reason the committing to paper is done quickly enough.’ This miraculous memory - he was said to be able to memorize an entire symphony having listened to it just once - enabled him to improvise new combinations. We see that power in Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus, a play about genius, when Mozart instantly recalls Salieri’s composition and immediately begins improvising something better out of it.

Bob Dylan also puts his creativity down to his juke-box memory, able to file away songs and ideas to draw on in his own compositions. He said in a fascinating speech last year:

For three or four years, all I listened to were folk standards. I went to sleep singing folk songs. I sang them everywhere, clubs, parties, bars, coffeehouses, fields, festivals…If you sang "John Henry" as many times as me – "John Henry was a steel-driving man / Died with a hammer in his hand / John Henry said a man ain't nothin' but a man / Before I let that steam drill drive me down / I'll die with that hammer in my hand." If you had sung that song as many times as I did, you'd have written "How many roads must a man walk down?" too…There's nothing secret about it. You just do it subliminally and unconsciously, because that's all enough, and that's all you know.

The secret of creativity, Dylan suggests, is ‘love and theft’ - curating your own inner juke-box or storehouse, and then shamelessly plundering it. Oscar Wilde agreed: ‘It is only the unimaginative who invent. The true artist is known by the use he makes of what he annexes, and he annexes everything.’

To be a great artist, you need to be a great critic, or rather, a great fan, loving what other people do, able to draw off them, absorb their influence without being possessed by it, and able to shake off or exorcise that influence when it’s time to move on, as Dylan channelled and then exorcised Guthrie, as Bowie channelled and then exorcised Dylan. And part of Bowie’s ‘scenius’ was also his genius for picking amazing collaborators - his wife Angie, Mick Ronson, Tony Visconti, Carlos Alomar, Robert Fripp, Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, Brian Eno. He could be incredibly generous in his support for other talent he considered overlooked, like Iggy Pop and Lou Reed. But there is also something agonistic in his collaborations - agon as in struggle. Harold Bloom understood the extent to which creativity is agonistic - there is another artist we admire, either living or dead, and there is a struggle to emulate and surpass, and creativity comes from that struggle. Lennon wrestles with McCartney, the Beatles wrestle with the Stones. Brian Wilson hears Sgt Pepper and makes Pet Sounds. And so on.

Bowie’s genius, then, was both internal - a product of his unique personality, the volcano of his subliminal mind matched with the cognitive power of his supraliminal mind - and external, in the circumstances and partnerships in which he found himself.

The dangerous cults of pop and religion

So what about Blackstar? What does his final testimony mean? As an early stab at it, I’d suggest it’s an exploration of his oldest theme - the cult of pop culture, its relationship to the older cult of religion, and how both can turn people into zombies. In the video for Blackstar, we see a jewel-encrusted skull in an astronaut suit (the remains of Major Tom?) which is carried solemnly into a circle by a devil-priestess with a tail. ‘On the day of execution’, he sings, ‘only women kneel and smile’, which reminds me of Dylan’s ‘they’re selling postcards of the hanging’. The skull is placed in a circle of women, who go into a sort of possessed trance, and dance - cut to three figures also dancing, possessed, in an attic. The dance they do is just like the dance done by the zombie-fashionistas in the video for Fashion, which Bowie described as being about how young people can be like 'lemmings' following the 'dictatorial will' of trend-setters ('listen to me, don't listen to me'). Bowie seems again to be suggesting that pop culture can be fascistic, that religious cults like ISIS can also be fascistic - we end up zombies following false prophets like Ziggy (who had ‘screwed-up eyes’ like the blind prophet in the Blackstar video), who only lead us on a road to nowhere. In Blackstar, he sings like a huckster-priest luring us to Syria:

I can’t answer why

Just go with me

I’m-a take you home

Take your passport and shoes

And your sedatives, boo

You’re a flash in the pan

I’m the Great I Am

The irony is, we’re all now dancing round his skull, obsessed and possessed by him, just like he predicted. We all need something to worship and copy, it saves us from having to think for themselves. But there's a risk of worshipping false idols - is there a higher light behind the blackstar? Bowie said in 1997, 'there's an abiding need in me to vacillate between atheism and gnosticism. I keep going back and forth between these two things'. I hope he found a light and can tell us all about it in the next Bardo.

Here's an interview I did with Brian Eno a couple of years back, on how the arts and religion help us surrender and go beyond the ego. And here's one I did with David Byrne on how the arts help us achieve a post-religious ecstasy and catharsis. And finally, here's a great essay by Tanya Stark on the influence of Jungian psychology on Bowie's work.

!['the demonic and irrational have a very disquieting share in that radiant sphere [of genius] and that there is always a faint, sinister connection between it and the nether world'. Thomas Mann, Dr Fausts](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c8bd3835239589598cac07e/1554973704689-QRTHTT38IDAESFFPAFUA/stc198813-300x231.jpg)