Everything Is Full Of Gods

The other day, I was watching Guillermo Del Toro’s Hellboy, and something struck me. Hellboy is based on a comic strip by Mike Mignola, about a demon from another dimension who is sucked into our world by a Nazi occult experiment gone wrong. Luckily for us, he’s a friendly demon, and he dedicates his life to protecting humanity from other demons, monsters and ghouls. He works at a secret agency attached to the FBI called the Bureau for Paranormal Research and Defense, where he is helped by a psychic merman called Abe. All pretty normal superhero stuff.There’s a scene later in the film, where Hellboy and Abe are fighting two hell-hounds known as Sammael. Abe has to go into a water-filled sewer to fight one of the Sammael, and Hellboy gives him a reliquary to protect him from the monster. While underwater, unfortunately, the merman drops the reliquary and, unprotected by is divine influence, he is attacked by the hell-hound.

What struck me about the moment was how completely Catholic it was. The good Protestant would scoff at the idea that if you hang on to some object, you are protected from evil, while if you let it go, you are in mortal peril from demons. Your only protection from the Devil, in Protestant thinking, was your conscience and moral will, not any reliquaries, talismans, rosaries or other magical objects.Such beliefs are much more common in the Catholic Church (so it’s no surprise to discover both Guillermo Del Toro and Mike Mignola are Catholic), but really they are older than Catholicism. They are animist.

Animism is the belief that, in the words of the Greek philosopher Thales, ‘everything is full of gods’. The world is teeming with spirits – earth spirits, river spirits, mountain spirits, wood spirits, house spirits, sauna spirits, demons, satyrs, angels, demi-gods, gods and the souls of our ancestors.

Humans, in an animist world-view, are more or less at the mercy of such spirits. Our psyche is like a rickety old shed that can easily be invaded by outside forces. We can be cursed by them, attacked by them and even possessed by them. On the other hand, we can win their favour and support, connect through them to our environment, and gain superhuman powers through their intercession. If we know how to control such spirits, we could rise even to the level of gods.Animism is the bedrock of humanity’s religious belief. It is what we all believed until very recently, and is what around 40% of the world’s population still believe. In Africa, for example, the most common mental disorder (if that is not an imposition of Western psychological terms) is still spirit possession. Spirit mediums can still sometimes play a major role in African civil wars, rousing armies to follow them with their claim to a direct link to the spirit-world, which they claim grants them special powers such as knowledge of the future or immunity to bullets.

Many Japanese people still believe in Shinto, and worship the kami, or spirits, whether of specific places or of deceased ancestors. I remember staying with a Japanese family when I was a teenager, and when I left being invited to say goodbye to my friend’s grandfather. I wondered where they kept the old man hidden away, and then was taken to a small shrine, where I rang a bell to say goodbye to the grandfather’s spirit.

In eastern Siberia, shamans still exist and practice. Shamans supposedly have the power to travel at will into the spirit world, and protect their tribes from the onslaughts of evil spirits and black magicians, while helping them to keep in favour with good spirits and the souls of ancestors. The shaman, through the help of the spirit-world, gains superhuman powers, such as the ability to fly, to heal the sick, to control weather, to communicate with animals, and to transform themselves into animals and birds. Similar shamanic beliefs existed among Native Americans, and still exist in the figure of the brujo of Central and South America.

Even in Europe, particularly in rural areas, many people still believe in ghosts, ghouls and nature spirits, and in the possibility of humans being possessed by devils. In Russia, for example, rural animist beliefs managed to survive the Soviet Union, such as the belief that domestic accidents are caused by the domovoy, or spirit of the house, or that you should make an offering to the spirit of the banya before using the sauna. Indeed, my neighbour when I lived in Moscow, a ballet dancer from the Bolshoi Theatre, believed the arts in Russia had declined because the spirit of Lenin was angry at not receiving a proper burial.

Animist or magical beliefs were very common in Western Europe up until the Protestant Reformation. Every parish would have its witch or cunning man who could ward off curses, read the future, interpret ominous dreams, communicate with dead souls, and give you amulets, charms or potions to protect you from bad spirits and win the support of good spirits.

The medieval Catholic Church maintained an uneasy truce with such animist and magical beliefs, and to some extent helped assimilate them into the Church, for example with the cult of the saints, with different saints supposedly having different powers to protect individuals from bad luck and devilry. St Christopher, for example, is considered the patron saint of travellers, and when I went on my Gap Year, my Irish grandmother gave me an amulet with his image on it, to protect me on my travels.

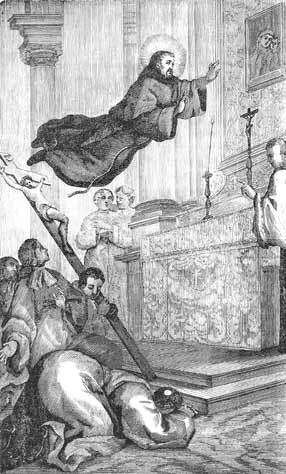

Saints assumed many of the powers of shamans and cunning men: the ability to prophesy the future, heal the sick, control the weather, encourage the harvest, magically transport heavy objects, and even fly. There was a levitating monk called St Joseph who inspired particular devotion. Indeed, he recently became the hero of a comic book.

One of the saints’ principal roles was to battle demons. Just as superheroes have their respective adversaries (Batman versus the Joker, Spiderman versus the Green Goblin), so saints, in medieval books of demonology, would be classified side-by side with the respective demons who they were particularly adept at defending against. Thus if you were plagued by the demon Gressil, you would call on St Bernard to defend you, or St Francis for the demon Belial, or St Peter for the dreaded Leviathan, and so on. The miraculous adventures of the saints and their battles with demons would be circulated among the masses in pictoral form via boldly-drawn woodcuts during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. These were perhaps early antecedents of the superhero comic book.

Saints would also be associated with specific places, with hills, mountains or caves, just as spirits had been before them. In Spain, you still have not one Mother of God, but several hundred. In modern Seville, for example, there are at least ten Madonnas, each associated with statues in specific churches and neighbourhoods, each with their specific powers, miracles and prayer-granting abilities. In such ways, popular animist beliefs have endured and survived even within monotheistic religions.

Such beliefs are not just the superstitions of the credulous masses. They also informed Renaissance magic, which was championed by some of the greatest intellects of the era, such as Pico Della Mirandola, Marcilio Ficino, John Dee and Giordano Bruno. For about a hundred and fifty years, after the fifteenth century re-discovery of Platonic and neo-platonist texts and Jewish Kabbalah, many European scholars believed they could draw down the power of the planets and even of angels through amulets, talismans, symbols and spells.

The Renaissance magus could, with the power of Kabbalah and neoplatonist hermeticism, command devils and angels, make statues speak and move, travel to astral spheres, channel the energy of planets, marry earth to heaven, and become akin to a God. “Behold now, standing before you, the man who has pierced the air and penetrated the sky, wended his way among the stars and overpassed the margins of the world”. Thus the Italian magus Giordano Bruno modestly described himself.

The Decline of Magic

And then came the clampdown. It started with the Protestant Reformation, which attacked the Catholic Church by claiming it was little better than a peddler of magic and witchcraft. The holy individual didn’t need wonder-working amulets, charms or icons, argued the Protestants. He needed prayer, good works, self-help, and the divine favour of the one true God. The Protestant churches banned the priestly office of exorcism; smashed Catholic icons, wood-carvings and stained glass window depictions of the miracles of saints; and then set about hounding out local witches and cunning men from rural communities.

An image from the comic Marvel 1602

This, in turn, helped spark the Catholic Church’s own Counter-Reformation, and its own frenzies of witch trials and heretic burnings, including a few unfortunate scholarly magi caught in the cross-fire, such as the magus Giordano Bruno, burnt at the stake by the Roman Inquisition in 1600.

But what really dislodged animist beliefs from the mainstream of European opinion was not the Reformation or Counter-Reformation, but the scientific and mechanistic world-view that superseded it. As Protestants increasingly emphasized the distinction between religion and magic, the spirit world receded more and more from nature, from fields, forests, rivers and mountains. The medieval and Renaissance world teeming with angels and demons was replaced by a world ruled by cold scientific and mechanistic laws, with God reduced to a distant watch-maker. As Keith Thomas has written in his classic historical work, Religion and the Decline of Magic: “The triumph of [Newton’s] mechanical philosophy meant the end of animistic conception of the universe which had constituted the basic rationale for magical thinking.”

Witchcraft, astrology, demonic possession and other magical beliefs became, in the eighteenth century, not so much threats to Christian orthodoxy, as simply old wives’ tales that no educated person would assert in public. Witchcraft stopped being a crime in mid-Eighteenth century English law, because judges simply stopped believing it was really possible to make a pact with the Devil.

The modern world, with its orderly laws of physics and economics, banished demons, sprites and angels to the kindergarten, to fairy tales written for children. Incidents of demonic possession were increasingly explained not by magic or religion, but by the fledgling science of psychology, as delusions brought on by melancholy or hysteria. By the early twentieth century, Sigmund Freud would define demons as repressed aspects of the unconscious haunting us until we integrated them. The psychologist had replaced the shaman and cunning man as society’s intermediary with the realm of the demonic.

Animism in the Folk Consciousness

And yet, if we examine the universe of comics and manga, we see that animist beliefs still exert a powerful influence over us, they still resonate in the folk consciousness. If these beliefs have been banished from the mainstream by Protestantism, Newtonian physics and liberal economics, they have not been entirely rooted out. First they retreated to eighteenth century fairy tales, then to Romantic literature and Gothic fantasy, until they found a particularly fertile breeding ground on the margins of our newspapers and in the pages of pulp magazines.

One can trace the history of these ancient beliefs, and see how the idea of the superhuman individual who gains his or her powers through a magical connection to the spirit world has endured, mutated, and somehow survived even in our rationalist and secular world. It was always stories told in words and pictures that carried these old folk beliefs. It was, in fact, the Protestant Reformation, with its attack on the image, which tried to sever this marriage of word and image, with its assault on the iconography of popular Catholicism. In some ways, comics have always been a rebellion against this Protestant divorce of word from image.

But why do we still need these old animist and magical beliefs? Is it just the remains of popular ignorance lingering at the margins of our minds like out-of-date tins of food at the back of the larder? What exactly do these animist beliefs in superhuman individuals do for us?

Animist beliefs give us the sense that there is a spirit world lying just at the margins of the mundane world of ordinary reality. You might fall down a rabbit hole, or walk through a cupboard, and suddenly you are in the spirit world. They give us a sense of mystery, of forces beyond our comprehension and control, peopling our otherwise banal environment. This is a much more exciting idea to the popular mind than the thought that our world is governed by unchangeable mechanistic laws.

What the magical view of the world promises us is that we, ordinary dim-witted mortals that we are, might suddenly stumble into the spirit world, and through bravery or sheer luck we might gain a boon there, a gift or a helper, which would give us extraordinary superhuman powers, so that we could return to the mundane world of the village or town, and dazzle our peers, impress the village wenches, and smite down our enemies and rivals.

If you look at the adverts for magicians in Kenyan newspapers for example (there is generally a whole section devoted to such adverts), the main services they offer is the ability to find hidden treasure, to cast love spells, to bring harm on one’s enemies, and to avert their curses. Such myths appeal to the ordinary individual’s sense that the world is a mysterious and confusing place, and wouldn’t it be great to have some magical talisman or familiar one could turn to in a tight spot.

The Superhero as Protector of the City

Animist hero myths also have an important civic function. One of the main things such myths ‘do’ is give us the consoling idea that our city is being protected from demonic or alien invasion. Hero cults are quite often connected with nationalism, with the idea of the souls of deceased heroes protecting the city-state from invading armies. Just as the shaman protects the individual’s psychic integrity by expelling the parasite demons, so the hero protects the city’s sovereign integrity by expelling or repelling invading forces at the city’s borders, or parasitic enemies lurking unseen within its walls.

Thus one of the most powerful hero cults in ancient Greece was the Spartan cult of the 300 warriors who gave their lives at Thermopylae to defend Hellas from the invading Persian army. Their sacrifice was thought so heroic that their souls were worshipped with blood sacrifices. Supposedly the souls of dead heroes had the power to protect the city from beyond the grave.

Icons and statues of the saints were also thought to grant protective powers to cities in battle. The Russian army carried icons out to fight the invading army of Napoleon, and when the Soviet Union came to make a statue commemorating the victory of General Zhukov over Nazi forces, he was depicted crushing the dragon of Nazism, as St George (patron saint of Moscow) had killed the dragon before him.

The hero-worship of the souls of fallen soldiers extended into the twentieth century, and can be seen in Nazism’s elaborate torch-lit rituals honouring the souls of dead German soldiers, who had supposedly been betrayed by the corrupt liberalism of the Weimer Republic. As late as this year, you perhaps see remnants of this sort of cult in the very emotional reaction among Russians to the Estonian decision to remove a statue commemorating the fallen soldiers of the Red Army, as well as moving the graves of the soldiers themselves.

The role of ancient hero cults in protecting the city certainly survives in superhero comics, in which the job of the superhero is pre-eminently the protection of the city. The superhero may occasionally save the world, but he is usually protecting the inhabitants of a specific city: Batman protects Gotham City, Superman protects Metropolis, Judge Dredd protects Mega-City One, and so on. Never mind the rest of the world, their main loyalty is above all to their City. The satirical superhero cartoon The Tick sends up this idea in its first episode, where superheroes attend a competition to see which city they will be allocated to protect.

The idea of statues of heroes protecting the city is perhaps echoed in the iconic images one often sees in comics of the superhero standing on the roof of a skyscraper, overlooking and protecting the city like a statue or gargoyle.

A lot of the time, superheroes protect their towns or cities from demons from the spirit world or underworld. This was the role of the shaman and the saint, and it endures in comics. Thus Buffy the Vampire-Slayer, created by the former comics writer Joss Whedon, protects her high school from the demons that pour from the hell-mouth beneath it.

But an equally important role is to defend the city from foreigners, from alien invaders, just as Asterix defends his village and its women from the armies of the Roman Empire.

It’s no surprise that the Golden Age of comics, in terms of sales, was during World War II, when superheroes like Captain America would often battle Nazi or Japanese forces in the pages of DC and Marvel comics. Indeed, at one point the Statue of Liberty herself became a comic book superheroine, battling invaders with her flame-throwing torch of freedom.

Releasing The Savage

The danger of such myths is that they speak to a very tribal and primitive part of our psyches, and tend to heroize the exploits of our own soldiers while demonizing the opposing forces. The pre-eminent role of the hero and superhero, we remember, is to battle demons. So superhero myths when used in actual battles tend to de-humanize and demonize foreign armies. As Michael Chabon has said of the success of WWII-era superhero myths: “They fought the Japanese and demonized them, but this was what superheroes were made for.” (The Nazis also used comics, to dehumanize Jews in the eyes of German schoolchildren - a method that was sadly all too successful.)

Superhero myths survived WWII, and new villains had to be found. Thus, in the Sixties, superheroes spent a lot of time fighting Communist Russia and China, and a new breed of supervillain was created, like the Black Widow, the sexy Soviet spy. We saw the jingoism survive and thrive in the British war comics of the 60s, 70s and 80s, with their endless battles of heroic Brits against the evil Fritz, the sneaky Jap, and the cowardly Italian.

We still see this demonizing of threats to the Western World in modern comics, for example, in Frank Miller’s re-telling of the heroic exploits of the Spartan soldiers at Thermopylae, 300. Both the comic book and the film turn the invading Persian army from humans into either faceless drones, or deformed and debauched monsters.

You might think, 'well, it’s just a comic book and not really related to modern politics'. But then you hear Frank Miller interviewed on American radio, discussing the War on Terror, and saying: “The entire western world is up against an existential foe… Nobody seems to be talking about who we’re up against, and the sixth-century barbarism that these people actually represent. These people saw people’s heads off. They enslave women, they genetically mutilate their daughters.” We might as well add that they eat babies.

So there’s a danger, perhaps, that superhero narratives play to a simplistic and tribal aspect of our psyches, and this primitive aspect of our psyche can still feed into modern politics. The American foreign policy strategist George Kennan, for example, warned of a very dangerous trend in American foreign policy, which was the belief that “if we lose, all is lost and life will no longer be worth living; there will be nothing to be salvaged. But if we win, then everything will be possible; all our problems will be soluble; the one great source of evil, our enemy, will have been crushed; the forces of good will then sweep forward unimpeded”. This is a fairly good description of the world-view of most American superhero narratives.Superhero myths are also frequently celebrations of lawlessness, in that the superhero exists beyond the confines of ordinary human law. Superman may stand for justice, but the justice he metes out is extra-judicial. As Alan Moore has said, if superheroes really existed, they would be psychotic vigilantes, less like Superman, and more like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver.

The idea of the superman as an individual beyond law or conventional morality goes back to Plato. It is expressed in Plato’s Socratic dialogue, Gorgias by Callicles, who says: “the makers of laws are the majority who are weak…But if there were a man who had sufficient force, he would shake off and break through, and escape from all this.” This is just what Nietzsche imagines in Thus Spake Zarathustra, when he dreams of a superman strong enough to leave the inhibiting morality of the weak, strong enough to leave the legal confines of the state altogether, and forge his own morality, becoming a law unto himself.

The idea was picked up by Nazism, with its idea of the Nazis as an elite, a band of Teutonic knights, who existed beyond conventional morality, beyond decency, beyond pity, beyond international law. And perhaps this worship of power finds fertile soil in superhero comics as well. The psychologist Frederic Wertham, whose critique of comics, The Seduction of Innocents, helped lead to the Comics Code of the 1950s, said once in an interview: “Superman himself is the symbol of force, power and violence. It’s impossible to understand what happened in [Nazi] Germany, unless you understand that they were imbued with this Superman spirit. It is the abolition of law, even the laws of physics.”

Superhero myths could certainly be said to be frequently undemocratic. The superhero is necessary because the democratic state does not work, is not capable of protecting its citizens from external threats. Politicians are often seen as corrupt, weak, decadent. Superman says in the first Superman film, “I’m here to stand up for truth, justice and the American Way”, to which Lois Lane replies “You’ll be fighting every elected official in the country”.

The opposite of the superhero is the journalist, ironically considering superhero strips would sometimes be carried in newspapers. The birth of newspapers, the mail and other devices of information technology in the seventeenth century helped to push animist beliefs to the sidelines, says the historian Keith Thomas: “The general effect of these trends was to keep the provinces more closely in touch with the metropolis, to break down local isolation and to disseminate sophisticated opinion.” The arrival of mass journalism is like the arrival of electric lighting: it sheds light, dispels shadows and improves transparency.

But the superhero loves shadows, darkness, secrets. That’s why Superman has to wipe Lois Lane’s memory when she discovers his secret identity. While the journalist is the champion of the masses, superheroes often belong to elitist esoteric groups that work in secret behind the scenes, or they work for covert government agencies that corrupt democratic politicians want to monitor or close down, as do the heroes of Men in Black, or Hellboy. It’s not that far from superheroes being the equivalent of extra-judicial death squads. Indeed, in Alan Moore’s The Watchmen, one superhero, the Comedian, does dirty ops for the US government, such as assassinating Woodward and Bernstein, the journalists who uncovered Watergate.

While the journalist is the champion of the masses, of the little man, in superhero comics the masses are weak and helpless – that is why they need the intercession of magical forces to help them. As Mohinder says in Heroes: “Without the special ones [ie superheroes], the challenges of modern times – global warming, terrorism, shortage of resources – seem insupportable on our frail shoulders.” This sort of thinking can of course become the elitist belief that you can divide humanity into worthless sheep and a few strong individuals who guide the destiny of mankind. It’s this sort of thinking that led to the hero worship of leaders among uneducated masses in Nazi Germany, Maoist China, or Soviet Russia, where the masses adored that other ‘Man of Steel’, Stalin, even as he ordered them to their death.

You could go so far as to say that superhero myths are a rejection of modernity. Two of the earliest proto-superheroes to appear as strips in American newspapers were Tarzan and Buck Rogers, who both made their debut on the same day in 1929. What we see in both of them is a flight from the present: into a primitive past or a noble future, in both of which things are simpler, moral lines are more clearly drawn, and the opportunities for violence and acts of individual heroism are many.

Superheroes are a flight from the rationalism of the modern world, from what Max Weber called the ‘Iron Cage’ of rationalism in Protestantism and the Spirit of Capitalism. Part of that rationalism, as Weber noted, was the bureaucratization of modern life: the welfare state, the NHS, the web of government agencies and regulations through which the modern individual must try to find their way. The superhero was born in the 1930s, during the New Deal, which was the greatest increase in the size and power of state bureaucracy yet seen in politics.

Superhero myths express a longing for a simpler kind of politics, for an earlier age, when the people felt a strong emotional bond to a charismatic warrior or prophet.

Weber defined the charismatic leader as akin to a superhero, in that the charismatic is “endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers or qualities. These as such are not accessible to the ordinary person, but are regarded as divine in origin or as exemplary, and on the basis of them the individual concerned is treated as a leader.” We remember that charis means gift in Greek, so it’s not so far from the Greek or animist belief that superheroism is granted as a gift by the Gods or the spirit world.

In a century of mass movements, mass production, mass employment – a century of the masses in other words – superhero myths celebrated acts of individual heroism. They hark back to tribal times when an individual could make a difference to the future of the tribe, could ‘save the day’. The heart of superhero myths, like other heroic narratives, is the trial by individual combat, the wrestle, the boxing match, the fighter-pilot dog-fight, the Western duel.

As Weber noted, the modern bureaucratic state asserts a monopoly on violence, while we long to escape from this cage, to indulge our pre-civilized desire to beat up, torture and kill our enemies. Comics give us an outlet for this bloodlust. They release the wild man from the iron cage.

This explains perhaps the many wild man heroes of comic books, such as Tarzan, Jungle Jim, Sheena Queen of the Jungle, Conan the Barbarian, Wulf the Barbarian, Slaine, or manga’s Violence Jack. These figures exist before the creation of the modern state, and are unhindered by its ban on unauthorized violence. They are free to give way to berserker rages, like the ‘raging furies’ of Captain Hercules Hurricane in the British comic Valiant, or the terrifying battle-paroxysms of the warrior Slaine, in the British comic 2000AD, who warps into a beast during battle by tapping into the energies of the earth goddess Danu.

This is part of the attraction, no doubt, of the ultra-violent graphic novels of Frank Miller, such as Sin City, 300, and The Dark Knight Returns. Miller’s characters, and perhaps Miller himself, hark back to a simpler time when we could indulge the bloody joy of torture and murder (in the defence of innocent women, naturally). In the final words of his graphic novel, The Big Fat Kill, as the hero and heroine machine-gun down a crowd of bad-guys: “the Valkyrie at my side is shouting and laughing with the pure, hateful, bloodthirsty joy of the slaughter…and so am I.”

Or you have figures who have a civilized, every-day self, and then a secret uninhibited, wild self, like Clark Kent and Superman, like Bruce Banner and the Incredible Hulk. The original for this type of split self is, of course, Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and indeed Mr Hyde has had an enduring influence on comics – he was a super-villain in Marvel comics of the Sixties, and a member of Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

So superhero comics are imperialist, jingoistic, anti-democratic, anti-civilization and devoted to the worship of uninhibited violence and (in manga) frequently rape as well. They come from the same dark, tribal and irrationalist part of the psyche that led to fascism.

Facing the Darkness

But we can’t say that comics created this part of our psyche. Perhaps they help us become more aware of it. Indeed, the present generation of comic book writers is very much aware of the amoral and even fascist strains in superhero myths, and they consciously explore them. The costume and character of Judge Dredd, for example, was consciously modelled on Franco-era Spain, although this, and the fascist tendencies of Dredd himself, did not seem to put readers off. “The more fascistic we made him, the wilder the readers went”, notes Dredd’s creator, Alan Grant.

Jamie Delano, creator of Hellblazer, has said that comics “are shining a light on the beast which crouches in the corners of our minds, giving us a chance to both recognize it and oppose it”. This is true of the most conscious hero myths – they make us aware that the demon the hero is fighting is actually a manifestation of his own psyche, a reflection of himself. This point is made in Martin Scorcese’s Taxi Driver, in the famous scene where Robert De Niro stands in front of a mirror and says ‘you talkin’ to me?’, practicing playing the heroic vigilante to his own reflection. The point Scorcese or writer Paul Schrader seem to be making is that this particular violent ‘hero’ is fighting his own shadow, his own demons, projected onto external figures.

We see a similar exploration of the hero myth in Sophocles’ Oedipus trilogy, which to my mind is the greatest hero myth we have in our culture. At the beginning of it, Oedipus the heroic slayer of the Sphinx and saviour of Thebes is trying to discover what evil lurks in the heart of Thebes. As the play carries on, Oedipus realizes that in fact he himself unconsciously committed the crimes he is investigating. He is the monster he is seeking, the shadow he is pursuing. When he discovers this awful and humbling truth, the chorus says:

“Some demon of the night,

Some destructive impulse in man, prowling

Silently around you, waiting its chance,

Has sprung with inhuman strength, howling

At your throat.”

And yet Oedipus’ true heroism is that he doesn’t project these demons onto others, and then blame them for his mistakes and suffering. He takes responsibility for them. He says: “I’m the one / Who must bear the guilt and the punishment / And the shame. And I must bear it alone.”

While the rest of us run from our demons or project them onto others who strike us as strange, alien or threatening, Oedipus has the moral courage and self-awareness to confront his demons, to endure their wrath, to endure the loss of everything he has. And yet this submission, this annihilation of his ego, leads to a transformation.

By the second play in the trilogy, Oedipus at Colonus, the demonic spirits that tormented him are placated, and become his helpers, granting him magical powers. He becomes a shaman-hero, in touch with the chthonic spirits, able to see the future and to read the signs of nature, and his body has magical powers to protect the city where he is buried. So the hero goes from being a demon-slayer to the integrator of the daemonic.

Why do we need such heroes? Civilization, as Freud told us, forces us to repress or hide the primitive aspects of our self – the violent, the sexually uninhibited, the wild.As we hide or repress these parts of us, they become demonic and hostile to our conscious selves. They attack our realities, trying to gain expression and release. Our selves become divided and at war, like Jekyll and Hyde.

At a simple level, comics, like dreams, provide an outlet for that which is forbidden by civilization. Manga, in Japanese, means “irresponsible pictures”. Comics take us to the forbidden underworld – that’s why so many superheroes live in caves, like the Batcave, and why comic book stores like Forbidden Planet in London are so often underground themselves.

The underworld is home to demons and monsters. But, if Jung is to be believed, it is also the source of our divinity, and home to powers and forces that we have forgotten, and to spirits that guide us on our journey. Joseph Campbell wrote: “the human kingdom, beneath the floor of the comparatively neat little dwelling we call our consciousness, goes down into unsuspected Aladdin caves…There not only jewels but also dangerous jinn abide: the inconvenient or resisted psychological powers that we have not thought or dared to integrate into our lives.”

Campbell suggests, rightly, that the highest hero myths provide us with a map for this journey. They “carry keys that open the whole realm of the desired and feared adventure of the discovery of the self”. And a crucial part of that discovery is the confrontation with our daemonic self, the parts of us we have hidden or left behind in the progress of civilization.

We must confront the Unconscious, recognize it, take responsibility for it and integrate it, if we are to continue on our journey to enlightenment. Campbell writes: “The hero…discovers and assimilates his opposite (his own unsuspected self) either by swallowing it or by being swallowed. One by one the resistances are broken. He must put aside his pride, virtue, beauty, and life, and bow or submit to the absolutely intolerable. Then he finds that he and his opposite are not of differing species, but one flesh.”

Very few modern superhero myths have the awareness to speak of this confrontation with the daemonic, and its re-integration. But some do. We think of the Star Wars trilogy, where Luke is training with Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back, and is told by Yoda to descend into a cave to confront his own dark side. There, he meets a dream image of Darth Vader, slays him, and then sees his own face beneath Vader’s mask.

This experience gives him the strength and wisdom not to fight Vader when he confronts him in Return of the Jedi. He has recognized that Vader is connected to him, is an integral part of him, to be integrated and transformed rather than slain. So he has the moral power to refuse to fight Vader, to refuse to give in to anger, and this submission transforms Vader into a magic helper – Vader kills the emperor and the Death Star is destroyed.

A similar mythical pattern takes place in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, which to my mind is the best drama there’s been on TV. Like many of Lynch’s dramas, Twin Peaks is an animist journey into the demonic realms that lurk below our kitsch civilization. FBI agent Dale Cooper is, in some respects, a superhero, in that he manages to win the supernatural help of magical spirits – the giant and the dwarf – in order to fight Bob, the evil wood-spirit that possesses various citizens of Twin Peaks. Eventually, he journeys into the Black Lodge, a mythical place within the woods, to try and save his girlfriend. There he confronts his daemonic self. We are told only those with a pure heart will survive this confrontation – only those willing to endure the annihilation of their ego. Unfortunately Dale seems to lose this challenge, and he has become possessed by the evil spirit Bob as the series end.

The greatest animation films to imagine a confrontation with and re-integration of the daemonic are Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke, and his earlier film Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind. These films are, to my mind, the greatest animation movies we have, together with other works of his like Spirited Away and Porco Rosso.

In Nausicaa, human civilization has managed to turn the planet into a wasteland. Most of the land is dominated by a toxic forest, guarded by slug-like earth spirits. The humans battle over what is left of the farmable land, and try to destroy the spirits and the toxic forest. The more they fight the spirits, the angrier and more destructive the spirits become. Nausicaa, however, realizes that the toxic forest is actually healing the earth, purifying it of pollution. She understands that the spirits, the protectors of the forest, are an important part of the eco-system, and that human existence depends on them.

At the end of the film, as the humans are trying to kill the spirits and the spirits are threatening the humans’ city with destruction, Nausicaa flies out to confront the spirits, and gives her life to calm them and placate them. Her sacrifice transforms their wrath. They are mollified by her sacrifice, and magically regenerate her. She becomes the saviour of the city – the intermediary with the spirit world.

The forest spirit in Princess Mononoke

Likewise, in Princess Mononoke, the world of humans has become out of balance with nature. The spirits of nature, no longer heeded or respected by humans, have become demonic, and try to attack and destroy human civilization. The nature spirits are led by a magical warrior-princess called Mononoke. The only person who doesn’t try to fight the spirits is Ashitaka, a warrior who has been wounded by a demonic boar. He sees that the nature spirits are just trying to restore the natural balance, and that they are necessary for the flourishing of life on the planet. He risks his life trying to intercede in the battle between civilization and the spirit world, and though the humans’ city is destroyed, a new and better civilization is born, one which will perhaps be more in harmony with the planet.

The superhero, in these films, is like the Romantic poet or the tragic hero. They are the heroic intermediaries between civilization and the spirit world of nature that humans have left behind. They are seized, possessed, by spirits, who drag them down to the underworld. The hero manages to overcome this challenge, this death of the ego, and to make peace with the spirits.

He or she then returns to civilization, as the ‘master of both worlds’, helping us to accept the daemonic parts of us that we feared, helping to re-connect us to the spirit world, bringing the conscious world into balance with the unconscious, and thus protecting the conscious world (or the City) from destruction at the hand of demonic or unconscious forces. And this re-connection to the spirit world is also a re-connection to the world of nature. As Coleridge put it, the poet (or hero) helps overcome “the enmity of nature” – that feeling that our civilized selves are fake, inauthentic, out of touch and even at war with our deeper nature.

This old belief in the possibility of an animist relationship with the spirits of nature has been rejected from the mainstream of Western liberal, rationalist and capitalist society. And yet we find it, like a diamond in a junk shop, in the cheaply-printed pages of superhero comics, through which is expressed the longing, as Michael Chabon puts it, “truly to escape, if only for one instant; to poke one’s head through the borders of this world, with its harsh physics, into the mysterious spirit world that lay beyond”.

So superhero comics can turn up a lot of nasty parts of the psyche – nationalism, tribalism, sexual violence, moral simplification, the demonization of enemies. They speak to a primitive part of the psyche, which often feels itself at threat from invisible forces that it does not understand and before which it feels helpless. At their most basic level, they can appeal simply to the longing for violence and domination which civilization forces us to repress.

But higher forms of the medium can do more than this. They can help us to recognize, accept and transform the darker parts of our psyche. They can make us feel re-connected to our selves and to nature. Our divinity, Jung suggested, lies waiting for us in the dark underground of our souls, if we have the courage to descend there.

The artist, in this model of art, is the real superhero. He or she has the courage to descend to the depths, like Orpheus descending to the underworld, in order to re-connect us to the spirit world, and thus to our divinity.

This belief in the artist as superhuman medium between the mundane and the spirit world goes back to the earliest human art, to the idea that the shaman drawing a picture of a buffalo on the side of a cave would somehow win the favour of nature spirits for the tribe’s next hunting expedition. Shamans, as we’ll see, are artists as much as they were priests or doctors. They go into trances, become hosts to spirits, and then sing, dance, declaim verse and paint pictures.

The idea of artist-as-shaman appears in Western culture via Plato’s definition of the poet as a person possessed by divine forces, unconsciously sending a message from the Gods. The Renaissance loved this idea, and used it to develop the idea of the artist or poet as magus, able to control spirits, as Shakespeare’s Prospero could control the air spirit Ariel. Marcilio Ficino, meanwhile, helped develop the idea of the Orphic poet, who could interpet the secret signs and correspondences of nature and control the influence of the planets with his music and verse.

When the Protestant Reformation and the ensuing scientific revolution pushed animist and magical beliefs to the sidelines, this belief in the magical power of art was also marginalized. The polite eighteenth century poet Alexander Pope might describe the spirit world in his poem, The Rape of the Lock, but his description is reduced to little more than an amusing literary device.

The Romantics, however, passionately resurrected this idea of the artist as spirit-vessel in their rebellion against the rational and mechanistic world-view of their era. The poet, in the works of Coleridge or Wordsworth, was a man possessed, seized by the spirits of nature and made to act as their conduit, their lightening conductor, in order to communicate their message to mankind. Or the artist was a sorcerer who created Golem-type animated figures, like Dr Frankenstein in Mary Shelley’s Gothic fantasy.

The last gasp of this exalted view of the artist in European culture was probably in the 1920s, with modernist artists like Kandinsky or Duchamp, both of whom were influenced by alchemical or shamanic ideas, and with modernist writers like TS Eliot or Antonin Artaud. But the anti-democratic and often pro-fascist stance of some of the key figures in modernism helped to further discredit the view of the artist as some sort of exalted emissary from the spirit world.

As our idea of art has become less and less exalted over the last century, so our conception of the poet or writer has calmed down, until the writer is now, in the modern mind, simply a peevish and vain man trying, like the rest of us, to get paid and get laid.

But at the margins of culture, below the radar of mainstream literary culture, the comic book artist rebels against this mundane and commercial view of art, and reclaims the exalted conception of the artist as shaman. Thus Alan Moore, one of the most famous writers in comics today, said in a recent interview: “I think that artists have been sold down the river… I think that over the last couple of centuries, Art has been seen increasingly as merely entertainment, having no purpose other than to kill a couple of hours in the endless dreary continuum of our lives. And that’s not what Art’s about, as far as I’m concerned. Art is something which has got a much more vital function.”

Moore takes the view that European art, up until the last two centuries, was profoundly influenced by magic, and even in the last hundred years some of the best art was connected with occult beliefs. The artist communicates with the spirit world, and connects mundane society to that world. Comics, he suggests, are resurrecting this old tradition.

He is himself a practicing sorcerer, seeing himself as in the tradition of scholarly magi like John Dee and Girolamo Cardano. Like those figures, he believes he has been visited by spirits from other dimensions, including by a snake god called Glycon that he connects to the Greek snake-god Aesculapius. In this, again, he is connecting to an old tradition in European culture – Sophocles also believed he was visited by the god Aesculapius in the form of a snake.

Other comic artists are also practicing magi – Alejandro Jodorowsky, for example, who wrote the cult comic series The Incal, is also a practicing tarot magician and healer. And the idea of the artist as shaman or spirit-conjuror is very much alive within comic narratives. The father of the modern comic is considered to be the German artist Rudolph Topfer, whose works including a graphic re-telling of the myth of Dr Faustus, who sells his soul to the Devil in return for superhuman powers.

Another of Goethe’s stories of spirit conjuring, a poem called the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, was a main influence on Disney’s Fantasia, where the sorcerer Yensid (Disney backwards) has extraordinary powers to channel spirits into household objects and make them dance at his command. If you think about it, what is Disney's Magic Kingdom if not an animist paradise - talking candles, smiling flowers, giant mice, dancing teacups...It is our animist past, recreated and repackaged as a theme park.

We see the neo-Platonic idea of the artist as a being possessed by spirits in the first ever issue of Spiderman, in which we see the writer Stan Lee sitting at his desk in the middle of the night, unable to sleep, with superheroes leaping around his head and resting on his shoulders like spirit familiars. The comics writer Neil Gaiman has also repeatedly explored the idea of the artist as someone who channels or makes pacts with spirits from other dimensions, in his comic series The Sandman. And the tradition has its most recent addition in the figure of the artist Isaac Mendez, who goes into a trance and paints the future in NBC’s Heroes.

So there’s a strange situation where comics, supposedly the irresponsible child of the ‘serious’ arts, is actually arguing for a more dignified and exalted conception of the arts than exists in the cultural mainstream. The comic artist, at least in their own conception, has a crucial role to play in our society, in connecting us to the spirit world that we left behind some two and a half centuries ago after the Protestant Reformation. We may not literally or consciously believe in these animist beliefs anymore. But the success of comics and superhero myths in the last 70 years shows that, whatever we say publicly, these myths still resonate powerfully in the folk imagination.