ISIS and the recurrent virus of apocalyptic beliefs

Probably the worst idea in the history of religion is the End Times. It’s caused more bloodshed than any other religious belief. It’s still around, costing lives - the ideology of ISIS is soaked in apocalyptic expectation, as a new book by William McCants explores. It’s amazing that the big religions have survived so long, considering how often their followers' totally certain prediction of the End Times turned out to be totally wrong. The Apocalypse has been announced many thousands of times over the last five millennia. And here we still are. Yet still the faithful declare the End.

What makes us keep falling for it? Perhaps it’s some inherent human frailty - in times of stress, psychologists suggest, humans are more likely to leap to strange or deluded interpretations and predictions, and we cling to them harder when faced with death. When the world is uncertain, when our position in it is threatened, we are more likely to believe someone who says they know exactly how this will play out. I remember when I had PTSD getting obsessed with palmistry and then astrology for precisely this reason.

Apocalyptic thinking goes deep into our psychology. Think of the mythical books and films we love in the 20th century, and their idea of the One who it is predicted will come to save us via a Final Showdown with Evil (in Dune, the Matrix, Harry Potter, Narnia, Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones). How satisfying those stories are to us - a clear narrative, with a beginning, middle and end, and clearly-divided Good Guys and Bad Guys. Candy for the soul.

But when played out in real life, such stories are a killer. They make the deluded of ISIS think that, because we’re in the End Times, anything goes - sexual slavery, mass executions, the beheading of elderly museum curators. Normal rules are suspended. All enemies must be wiped out.

The idea of the End Times goes back at least as far as 500 BC, when Zoroastrians started to talk of an environmental collapse and a final confrontation between Light and Darkness before a perfect age for the righteous. Judaism also came to expect the coming of a Messiah, a new King, who will utterly smite Israel’s enemies, liberate Jerusalem, and then rule in a perfect age where ‘the wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard will lie down with the goat, the calf and the lion and the yearling together; and a little child will lead them’.

Jesus was certain the End Times were just around the corner: ‘these things will come upon this generation’, he is quoted as saying in the Gospel of Matthew. ‘There be some standing here, which shall not taste of death, till they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom.’ St Paul was also certain the End Times were nigh. The general Christian expectation of the End of Days led to a proliferation of apocalyptic texts in the first and second centuries, with one particularly florid vision - Revelation - eventually being accepted into the Canon, despite the misgivings of some Church Fathers.

But the End Times didn’t happen. Instead, much to everyone’s surprise, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. Nobody predicted that! Then the Roman Empire got sacked by Goths, leading to another bout of apocalyptic fever. But life went on. Then Mohammad saw an angel, who told him of a coming apocalypse when the Al-Mahdi would descend from heaven, riding a white horse and accompanied by Jesus, to utterly smite Islam’s enemies (particularly the Jews) and liberate Jerusalem . This Messianic expectation fired up Islam for one of the most extraordinary military expansions in human history. But they didn’t conquer the world, and the Mahdi didn’t come. Life went on.

All through the Middle Ages, societies would be suddenly convulsed by apocalyptic expectations. A monk, knight, shepherd or vagrant would announce they had received a vision from God - often they claimed to have found an ancient prophetic text or to have received a personal letter from Jesus - and they were destined to liberate Jerusalem, convert the Jews, and usher in the thousand-year reign of the saints (hence such movments were often called 'millenarian'). Again and again, from the 11th to the 14th century, such people persuaded thousands to follow them to Jerusalem or somewhere nearer, often massacring Jews along the way. Usually they and their followers were executed, starved, or died in battle. And still the End Times didn’t happen. Life went on.

Throughout the tectonic shifts of the Reformation, many people believed they were living through the End Times, and the leading figures of the day - Martin Luther, the Pope, the Emperor, Henry VIII, whoever - were either the Saviour of Christendom, or the Anti-Christ. This being the End Times, normal rules were suspended - the enemies of the True Faith must be purged from the Body Politic, and the poor old Jews converted or massacred. This 150-year religious fever culminated in the Thirty Years War, a long orgy of violence that killed roughly a third of the German population. And still the End Times didn’t happen. Life went on.

Finally, by the end of the 17th century, people in western culture were fed up with apocalyptic predictions. After 2000 years of false alarms, after thirty years of apocalyptic warfare ended in stalemate, people started to doubt that the End Times were actually upon us. As life became more stable and prosperous, people’s focus shifted from the End of Days to making life slightly more pleasant here on Earth. The ecstatic predictions of prophecy gave way to the cautious predictions of science.

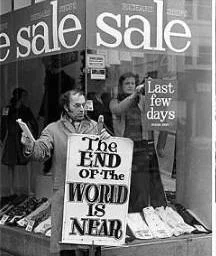

Where before an apocalyptic prophet could be guaranteed a listening, now they became objects of ridicule. When French Huguenot prophets arrived in London in 1706, and started to go into apocalyptic spasms in the streets, they were laughed at, and even inspired a puppet show at Bartholomew Fair. This sort of ‘public raillery’ was the best antidote for such enthusiasm, declared the Earl of Shaftesbury. It worked much better than suppression, which only further agitated their melancholic self-importance. From that point on, apocalyptic prophets became figures of fun, pity, and medical interest - they evolved into the comic stereotype of the lonely nutter wearing a sandwich-board, announcing the End is Nigh.

There were still many apocalyptic movements during and after the Enlightenment, like the Jansenist convulsionnaries of 1727, a group of End Time ecstatics who went into spasms until a violent beating calmed them down (see the illustration below); or the Seventh Day Adventists in the US, led by William Miller, who announced the End of Days would arrive on 1843. It didn’t (this is known as The Great Disappointment), but that didn’t stop the movement - every day I walk past one of their churches on the Holloway Road. But such apocalyptic Christian cults tended to be marginal and relatively harmless.

Whenever Christianity becomes ecstatic, it involves an expectation of the End Times. The Pentecostalists of the early 20th century, for example, thought they were granted miraculous powers like speaking in tongues as a sign of the Second Coming. As the Church of England becomes more charismatic, some church leaders also nurse apocalyptic hopes. Pete Greig was the youthful leader of a 1990s charismatic revival, which he wrote about in Red Moon Rising. The title comes from a verse in the Book of Joel predicting the End of Days - Greig apparently thought his revival was a Sign of the End Times. But it wasn’t. Life went on.

My next book argues that we need to find a place for ecstasy and altered states of consciousness in modern rational society. But apocalyptic expectations are the most troubling aspect of ecstasy. So often, what has really fired up ecstasy is the belief: ‘the old order has passed, here comes a New Jerusalem!’ And that belief is not confined to theists, by the way. In different forms, it inspired the ecstasy of the French Revolution, or the worship of Hitler, or even the dot.com bubble (in which the New Jerusalem became the New Paradigm). 'Atheism is not exempt from it', remarked Shaftesbury. 'For, as some have well remark'd, there have been enthusiastical atheists.'

I suppose the ecstatic belief that things can be radically better can be a good thing, and can help to drive change. What is dangerous is the totally certain expectation that a final apocalypse is at hand and that the human population can be neatly divided into sheep and goats. That’s a horrible idea, one that has been proven wrong over and over and over again, as the unhappy survivors of ISIS will soon discover.