Modern Ecstasy, or the art of losing control

Here's a transcript of a talk I gave at Radio 3's Free Thinking Festival last month, which was broadcast last week (you can download the podcast here).

I’ve spent the last year researching the history of ecstatic experiences. This might seem like a strange way to spend a year - don’t worry, it’s not tax-payer-funded. Here’s why I think ecstasy is interesting, and important.

Lots of people have ecstatic experiences in their lives. And they are often life-changing moments. They can be profoundly healing moments, when a prison door swings open and they suddenly get released from destructive habits, narratives and lifestyles.

The search for ecstasy can also be dangerous. We can seek it in inappropriate ways - through extreme violence, extreme drug-abuse, extreme sex, extremist politics. And what makes ecstasy so interesting is that it is profoundly uncertain, particularly in our postmodern, post-religious era. Are we really connecting to something or someone ‘out there’, or is it just a nice feeling?

I’d like to compare the modern self to a rickety old shed in a forest. Sometimes we seem to hear or see or connect with things beyond or beneath that shed - and how we interpret those liminal experiences has a huge impact on our world-view and our life. But our interpretations are ultimately uncertain. We can’t be sure if there really is something out there, what it is, what it wants with us, or whether it was just the wind in the trees.

What is ecstasy?

So, let’s begin with a working definition. Ecstasy comes from the ancient Greek exstasis, which literally means ‘standing outside’, and more figuratively means ‘to be outside of where you usually are’. In Greek philosophy, in Plato and Neoplatonists like Plotinus, it came to mean moments when a door opens in your mind or soul, you feel an expanded sense of being, an intense feeling of joy or euphoria, and you feel connected to a spirit or God. Its closely connected to another word in Plato, enthousiasmos, which means ‘the God within’. So in moments of ecstasy, according to Plato, you stand outside of yourself, and God appears within you.

Ecstasy can happen in two ways, according to Plato. The best way, according to him, is the way of the philosopher or mystic, who over years and years of contemplation frees their soul from ignorance and finally attains an ecstatic knowledge of the Divine.

The other path is the way of the artist or seer, who suddenly gets seized by God and goes into an ecstatic trance, a sort of divine madness. And their art can carry us all off into a rapture too. Plato thinks this is inferior because the artist or seer doesn’t really understand how this inspiration happens or when it will occur. They just have to put a fishing line down into the sea of their unconscious, as David Lynch puts it, and hope that a big fish bites.

Now in these days of scientific materialism and economic utilitarianism, you rarely hear anyone make the Platonic defense of the arts - that they are ecstatic transporters which take us beyond our ordinary selves and connect us to something supra-human. But I happen to think it’s a good defense, and one still held by many artists, from Ted Hughes to Jeanette Winterson.

Let me quote Christopher Hitchens in support of the Platonic view of the arts. Hitch says:

I’m a materialist…yet there is something beyond the material, or not entirely consistent with it, what you could call the Numinous, the Transcendent, or at its best the Ecstatic. It’s in certain music, landscape, certain creative work, without this we really would merely be primates.

That’s a very interesting statement - the Ecstatic is, according to Hitchens, something that brings profound meaning to our lives, something that lifts us above the merely Darwinian, yet it’s also something hard to pin down and quantify, a bit like the angel that Jacob wrestles with who refuses to tell him its name. The best way to explore it, perhaps, is through our personal accounts of it, so let me crash through all academic barriers and tell you one of my own ecstatic experiences.

As those of you who’ve read my book will know, I suffered from social anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder for five years or so in my late teens and early twenties. I was stuck in a narrative of having permanently damaged myself, and my life had become a wasteland.

Then, in 2001, I went to Norway with my family, as we do every year, usually we go cross-country skiiing but this year, fatefully, on the very first morning, I followed my cousins down the black slope of a mountain called Valsfjell. The visibility wasn’t very good, and I’m not a very good skiier, and I crashed through the fence on the side of the slope, fell thirty feet, broke my leg and three vertebrae, and knocked myself unconscious.

When I awoke, I saw a bright white light, and I felt filled with love. I had a sudden deep sense that there was something in me, in all of us, that can’t be broken, that can’t be damaged. I felt that what had caused all my suffering was not actually some chemical dysfunction in my brain, it was my belief that I was damaged. I could let go of this belief, and trust in my soul, in what the philosopher Epictetus called the God within.

Now this experience was incredibly intense. But it was also somewhat uncertain. Was that white light something outside of me, or within me? Was it simply my body reacting to trauma with a surge of dopamine? If it was something Other, was it God, or a spirit, or a Higher Intelligence, or what?

All I know for sure is that this moment of ecstasy was enormously helpful and healing to me. It opened a door, and freed me from the narrative of being permanently damaged, which I’d been stuck in for the last five years. I could let go of that toxic belief, trust myself, and begin to heal.

So I went on to write a book about Greek philosophy, trying to spread this idea that it’s our beliefs rather than our neurochemistry that often causes us suffering. Ironically, the book is very much about the power of self-control and self-knowledge, despite the fact it emerged from an experience beyond my control and beyond my knowledge. I didn’t talk much about that experience on the mountain, because I was worried people would think I was crazy.

Ecstasy and the Enlightenment

That is, I think, quite a common view-point in Enlightenment societies. Many people have ecstatic experiences, and find them deeply meaningful, but they keep them to themselves, for fear of what others might say.

As historians of ecstasy like Michael Heyd have explored, one of the things that happened during the Enlightenment was that some philosophers sought to discredit, ridicule and marginalize ecstasy. The Enlightenment came after two centuries of religious wars, and philosophers like David Hume and John Locke quite rightly thought that ecstasy, or enthusiasm as they called it, often led to fanaticism and religious violence. A person or group has a revelatory experience, and then insists that their revelation is the only path to God, and all other paths are demonic. That’s not a very useful attitude for a tolerant, multicultural society.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, enthusiasm was pathologized - it was seen as a form of mental illness, similar to what we’d call manic depression today. Enthusiasts - people who claimed to have a divine connection to God - shouldn’t be listened to, they should be educated, or mocked or if necessary locked up.

Ecstasy was what JGA Pocock called the anti-self of the Enlightenment. According to Enlightenment philosophers like Adam Smith, we should remain rational, self-controlled, polite and industrious at all times. Ecstasy is the complete opposite of that - non-rational, out of control, wild.

When modern academic subjects like sociology, anthropology and psychology emerged in the late nineteenth century, they defined themselves as serious scientific disciplines by coming up with naturalistic explanations for ecstatic experiences. The sociologist Max Weber argued that 'charisma' was a stage on the evolution to the triumph of rational bureaucracy. According to early anthropologists like Sir Edward Burnett Tylor, for example, ecstasy is a sort of trance state that happens to primitive people in undeveloped cultures. According to early psychologists like Freud or Charcot, ecstasy is a form of automatism or hysteria that happens to weak, neurotic and irrational types like women or Welsh people.

But some academics tried to find a more positive explanation for ecstasy. The sociologist Emile Durkheim suggested that moments of collective ecstasy are an important form of social bonding - think, for example, of how the euphoria of the Olympic Games brought people together.

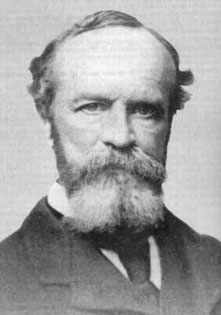

The psychologist and philosopher William James, meanwhile, suggested, in his 1902 book The Varieties of Religious Experience, that science might not be able to prove where ecstatic experiences come from, but it could show that they often genuinely healed people, helping to liberate them from destructive habits like alcoholism (indeed, his book was one of the inspirations for Alcoholics Anonymous). They might be accessing some healing power in their unconscious, or it might be some healing power ‘out there’ in the cosmos - either way, something beyond their rational everyday self was helping them.

James hoped that his book would provide a scientific defence for Christianity in an age of skepticism. In fact, his work helped to create a whole new demographic - the ‘spiritual but not religious’ - by showing that people have ‘spiritual experiences’ in many different religions, and also outside of any religion. Indeed, people often seem to have spiritual experiences on certain drugs - a 2011 study at Johns Hopkins Medical School gave magic mushrooms to 18 volunteers, of whom 17 said it was one of the most meaningful and spiritual experiences of their life.

Secular ecstasy

And it was not long after James’ book came out before atheists insisted that they also had ecstatic experiences. In the 1960s, a Radio 3 journalist named Marghanita Laski undertook a survey on ecstatic experiences, and found that atheists had just as many as believers. Respondents described ecstasy as a feeling of fullness, expansion, surrender, a sense that all was well in the world; typically they reported experiencing such moments less than a dozen times in their life.

Laski was particularly interested in what had triggered such experiences - the most frequent trigger was sex, closely followed by classical music - particularly Beethoven. This led Laski to conclude that Radio 3 listeners felt far more ecstasy than the rest of the population - she couldn’t accept that people felt ecstasy listening to the cacophony on Radio 1.

This was rank snobbery on Laski’s part. In fact, for most people today, pop music is our main pathway to ecstatic experience. Rock and roll and rhythm and blues grew out of the gospel music of Baptist and Pentecostal churches, and provided a sort of church for the unchurched. Pioneers like Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Ray Charles, James Brown and Tina Turner took the screams, wails, whirls and frenzies of Pentecostal worship, and brought them to an ecstasy-starved white audience. In our very self-controlled, rational and atomised society, rock and roll provided a place where people could lose control and come together. Rock and roll was, I'd suggest, the Third Great Awakening in American religion.

According to the musician Brian Eno, ecstatic experience emerged as a biological adaptation, teaching us to surrender and accept the limits of our control. Religion, Eno told me in an interview this year, used to be the way we got our hit of ecstatic surrender, but now we mainly get that experience from the arts, particularly music.

Eno is a committed atheist, and insists that one can have the experience of ecstasy without any religious beliefs. He used to go along to sing with a gospel choir in New York, he was the only atheist in the choir, but he insists he got exactly the same experience of ecstatic surrender as all the believers.

I wonder if that’s true. Let me end this evening by asking if we can really detach the emotion of ecstasy from particular beliefs.

If you listen to some of the ecstatic anthems that Eno has helped to produce, like U2’s Where the Streets Have No Name or Talking Heads’ Once In A Lifetime, they are not just good feelings. They also embody a particular attitude which I think is key to ecstasy: a belief or faith that the universe is a good place. Eno has said of gospel music: ‘The big message of gospel is that you don’t have to keep fighting the universe; you can stop and the universe is quite good to you. There is a loss of ego.’

Here's David Byrne talking about how Pentecostal and Baptist worship inspired Once In A Lifetime:

So I would suggest that ecstasy is not just a feeling but an attitude of cosmic optimism - a belief that the universe is good to you. And this is also tied to an optimism about human nature - a belief that if you let go and journey beyond the ego, you might find not just dragons, but also hidden treasure, healing power and creative inspiration.

And ecstatic experience also embodies hope about the world, and an expectation that the human society is becoming or could become radically better, regenerated, renewed. Of course, that expectation is consistently disappointed. Throughout history, people have thought they were entering a new age of love, and time has continually proved them wrong. It’s a history of waves of hope and troughs of despair. And yet hope springs eternal. Humans need ecstatic experiences, particularly in historical moments when we feel we’re stuck and there’s no way out.

Our society is very good at emphasising the need for self-control. It is, I’d suggest, the central moral value of our rational industrial scientific era. What we have forgotten is the the art of losing control without damaging yourself and the people around you.

More on the link between Pentecostal worship and rock and roll - check out Janelle Monae on Jools Holland in September, performing 'Dance Apocalyptic' (which taps into a rich vein of millennarian funk in Afro-American music going back through Gnarls Barkley, Prince, George Clinton, James Brown and others). At 3 minutes, she shouts 'here comes the Holy Ghost!' then falls onto the floor in a mock-trance.

*******

In other links (for subscribers to my weekly newsletter):

Today is the centenary of Alfred Russell Wallace, the other discoverer of evolution, the theory of which came to him 'in a millenarial fit in a jungle in South-East Asia', as Bill Bailey put it. A fascinating figure, who thought God sometimes intervened in evolution. Darwin was also prone to the occasional ecstatic moment, by the by. He wrote of his time in the jungle, in The Voyage of the Beagle: 'It is not possible to give an adequate idea of the higher feelings of wonder, admiration, and devotion which fill and elevate the mind ... I well remember my conviction that there is more in man than the mere breath of his body.'

Right, time to sober up. Here's Gregory Tate on how Jane Austen's rational heroines anticipate the insights of behavioural economics.

The Stoicism for Life conference approacheth - on November 30, in London. You can register and see the roll-call of great speakers here.

Here's an interesting article on the first public placebo-controlled trial- by Benjamin Franklin, to debunk Mesmerism.

Here's a video of me and others discussing the old 'can governments measure and enhance well-being' question, at the Legatum Institute last week.

An important part of the politics of well-being involves learning how to sleep better, argues Simon Williams in the RSA Journal.

Thomas Nagel argues moral psychology (a la Joshua Greene) needs moral philosophy.

Great FT piece on Lou Reed, and here's Laurie Anderson's Rolling Stone cover story on her husband.

Here's Cambridge PhD Andy Wimbush on Samuel Beckett and Quietism.

Open University has launched an online philosophical 'choose your own adventure'!

The Reith Lectures by Grayson Perry ended with another brilliant talk. One of my favourite things this year.

Right, that's your lot. Thanks for emails asking how you can donate to the blog, below is the PayPal link (you could donate a tenner for the year, for example). Hopefully it works. My PayPal name is julesevans.

Jules