On Experimental Religion

I, like many other people (at least 15% of the adult population and two thirds of all children, according to the latest psychiatric research), have ‘out-of-the-ordinary' or 'psychosis-like experiences’, where I feel connected to an external supernatural force - or God, as I call Him. For me, the experience is not usually of a voice or a vision, though I had those once or twice in my youth, it’s a powerful feeling of bliss which comes over me and fills me, an experience which I have felt a handful of times when worshipping in church, and which I attribute to God. From a psychiatric point-of-view, the supernatural attribution renders my experience 'psychotic-like', rather than merely pleasant.

I don’t have such experiences very often, alas, but I do have them, and they’re wonderful, enriching, meaning-giving moments. Maybe you have such experiences too, in nature, in music, in dreams or visions. But it’s dangerous to talk about them openly because such experiences have - since the Enlightenment - been pathologised as symptoms of madness. You'd better shut up about it, unless you happen to be a male, white, middle-class Romantic poet.

The Enlightenment called such ecstatic experiences ‘enthusiasm’, and pushed them to the margins of society. Enthusiasm was the plague of the polite, tolerant, mercantile Enlightenment, its 'anti-self' as the historian JGA Pocock has put it. Enthusiasm was what stirred up wild-eyed fanatics like the Quakers, Ranters, Huguenots and Anabaptists, who were blamed for aggravating the religious violence of the 16th and 17th centuries. They felt communicated to by God and then, unfortunately, they sometimes became convinced that they were uniquely blessed, everyone else was damned, that the Final Reckoning was just around the corner. So, in the calm, polite culture of the 18th century, any claims to a divine connection to God was medicalised and pathologised - 'enthusiasm' was a natural illness caused either by melancholy, animal spirits, or social contagion, something to which women and Africans were particularly susceptible. You'd do well to keep such experiences to yourself, or you’d be ridiculed, blackballed, even locked up.

I believe we lost something as a result of this excision of human experience. The Enlightenment freed us from many old tyrannies - the tyranny of kings and priests - and from many old superstitions. But it also deprived us of ecstasy, and the ecstatic feeling of being connected to God. This feeling is, for me, one of the core human experiences.

We, as children of the Enlightenment, are frightened by such experiences, because we’re frightened of losing control of ourselves (this is the primary cardinal sin of the Enlightenment), and we’re also afraid of being ‘brainwashed’ and surrendering to a collective authority (surrendering autonomy is the second cardinal sin of the Enlightenment). And, as a society, we’re afraid that if we start treating ecstatic or revelatory experiences seriously, if we switch off our demand for tangible evidence and trust in our intuition, it will open the door to all sorts of crazy beliefs. Before we know it, we’ll be surrounded by crystal skulls and peering into tea leaves. Or worse - our calm, reasonable society will once again become a battleground for hordes of ecstatic nutters running around convinced that God told them to decapitate their enemies.

I appreciate that unwillingness to let go entirely of the safety rail of critical thinking and scientific evidence. My best friend developed schizophrenia when he was 16, after taking LSD. He became haunted by voices, which he sometimes interpreted as demons, sometimes as angels, sometimes as symptoms of his illness. They'd tell him to do violence to himself and others. He remained more or less at the mercy of them, unable to hold them to rational account. I have seen for myself what it’s like to be at the mercy of your superstitions.

Nonetheless, I don’t think ecstatic experiences are all bad. They’ve occasionally helped me, guided me, given my life a sense of meaning and emotional richness. I think we need to find a way to talk about such experiences, to see the good in them, and to rehabilitate them in our hyper-rational world. We need to find a balance between revelation and reason, between the scientific and the sacred.

This week, I’ve been reading about two religious revivals of the early 18th century, two resistance movements to the Enlightenment’s war on Enthusiasm. One was the First Great Awakening, which swept through the American Colonies like a hurricane in the 1730s. The other was the Methodist movement, which tore through England and Wales at the same time. Both movements were widely condemned as enthusiastic - at meetings, people would faint, cry out, leap for joy, feel filled with the Holy Spirit, and even have visions of Heaven and Hell. It was all very unreasonable and uncontrolled.

The priests involved in these revivals were faced with a tricky task. On the one hand, they didn’t want to condemn such collective ecstatic experience as merely ‘enthusiasm’ - the revivals had led to the conversion of tens of thousands of people in America and Great Britain. And such passionate religious experience seemed to many people to be far better than the ‘formalism’ of rational Christianity, or Deism, which obeyed the Scriptures without really feeling close to God. On the other hand, they didn’t want their movements to be too enthusiastic, too marked by short-term emotional excesses rather than genuine and long-term holiness. And they were aware that sometimes, such collective ecstasies might be natural psychological phenomena rather than supernatural visitations by the Holy Spirit.

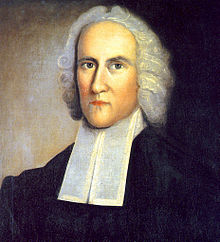

Jonathan Edwards, a theologian involved in the First Great Awakening, proposed a middle-ground which he called ‘experimental Christianity’. He warned that it is possible for ‘flashy’ emotional experiences (fits, visions, ecstasies etc) to be ‘neither accompanied nor followed with a Christian behaviour, and this is worse than nothing’. Many people, caught up in the hullabaloo of the Great Awakening, may have simply been swept along by the commotion, without really turning their heart to God. They fell into fits and ecstasies not, Edwards warned, because of the Holy Spirit but simply because of ‘example and custom’ - everyone else was shaking, jumping and passing out, so they did too.

Our modern theories of social contagion come, by the by, from Enlightenment theorizing about collective ecstatic experiences - the Earl of Shaftesbury wrote in 1707 of ‘panics’ - by which he meant any collective passion - ‘which are rais’d in a Multitude, and covey’d by Aspect, or as it were by Contact, or Sympathy...And in this state their very looks are infectious’. Today we talk of such panics mainly in an economic context - it’s interesting that, as soon as the Enlightenment banished religious ecstasy, it re-appeared in the supposedly rational marketplace in the form of market manias like the South Sea Bubble of 1711. As Jung once said, you can drive Nature out of the door but it will fly in through the window. But I digress.

Edwards suggested that ecstasy must be held to the test of experience, to see what fruits it actually leads to. He wrote: ‘This is properly Christian experience, wherein the saints have opportunity to see, by actual experience and trial, whether they have a heart to do the will of God, and to forsake other things for Christ, or no.’ He added that just as ‘that is called experimental philosophy, which brings opinions and notions to test of the fact, so it is properly called experimental religion, which brings religious affections and intentions to like test.’

John Wesley, the founding father of Methodism, likewise tried to tread a fine line between formalism and enthusiasm. He wanted Methodism to be a ‘religion of the heart’, in contrast to the over-rationalistic Deism prevalent in the 18th century. He insisted that the ‘inspiration of God’s Holy Spirit’ is ‘the very foundation of Christianity’, and that Methodists had been blessed with ecstatic experiences in order to carry them to the rest of Christianity. This is, in fact, what happened over the next two centuries, first through Pentecostalism, and then - since the 1960s - through modern charismatic Christianity.

On the other hand, Wesley wrote that ‘Dreams and visions were never allowed by us to be certain marks of adoption’ [ie to give certain proof of your sanctification]...Neither did we ever allow the falling to fits (whether natural or supernatural) to be a certain mark.’ He remained somewhat ambivalent about ecstatic experiences to the end of his life. Sometimes he would take ecstatic phenomena as ‘signs’ that the Holy Spirit was blessing a particular gathering, other times he would warn not to put too much emphasis on such phenomena (while also not disregarding them altogether).

Edwards’ and Wesley’s early attempts to build an ‘experimental religion’, which balances an acceptance of ecstasy with an emphasis on the proper tests of such experience, could be useful to people like me, who occasionally feel such experiences but aren’t quite sure what to make of them.

The risk is that one puts complete emphasis on them, and end up with a religion entirely of the heart, where you are greedily seeking out emotional highs rather than trying to serve God - a sort of ‘extreme sports’ version of religion. Another risk is that, when such initial experiences subside (as they typically seem to do), you feel somehow abandoned by God, like a Romantic poet suffering from writer’s block. A serious risk is that you become grandiose in your ecstasy, puffed up, convinced you are one of the Elect - when in fact such experiences seem to be quite common. You may be also convinced your particular religious path is the only way to God. You have every right to think your path is the best way (it would be hard to be a Christian and not believe that), but it's also good to be humble and to accept you don't know the full picture.

Perhaps we can enjoy such experiences, while also holding them up to the test - do they lead to a better and more holy life? I think that’s probably up to us more than the Holy Spirit. In that sense, I guess, I’m not a Calvinist or Anabaptist or Pentecostalist - I don’t think the occasional experience of the Holy Spirit means you are wiped entirely free from sin and are sanctified for ever, just as I don’t think falling in love means you’ll definitely be a good husband your whole life. Falling in love may be involuntary, it may hit you like a bolt out from the blue. Staying in love and building a marriage is a different matter - it involves hard work (as well as the occasional moment of bliss).