PoW: Evidence-based Easter, and other curious phenomena

Can we create a rational, evidence-based spirituality? Many interesting thinkers, from Richard Layard to Sam Harris, are working on just this project. As Layard said at the RSA this week: “What I think I’m arguing for is a new secular spiritual culture…a new moral culture based on reason, using the new science of happiness.”

Of course, Christians also think their religion is rational and evidence-based. The evidence, for them, was the empty tomb, it was Jesus appearing to his followers on Easter Sunday. The evidence was all the signs, wonders and miracles attributed to Jesus and his followers up to the saints of the present day. People stopped believing so much in this sort of evidence in the 18th century, because of the development of the experimental method, and the work of rational sceptics like David Hume and Voltaire, who took great pleasure in showing up the superstition of popular miracle tales, and the illogicality of using Bible quotations as ‘proof’ of Christianity’s truth.

Under the attack of scientific rationalism, Christianity tried to re-define itself in more rational terms. The 18th century Deists, for example, pointed to the perfection of nature, and asked if such perfection could have been created without intelligent design. But thinkers like Hume argued that creation was, in fact, far from perfect. Most created beings live lives of want and suffering, and nature seems to care very little for its creations. And after all - what about the Dodo? Why did God create it, just for this pathetic creature to die out? The wonders of nature could be much better explained through the idea of what Hume called a ‘blind principle’ of creation, or what Charles Darwin would later call natural selection. Life is driven by our selfish genes and their blind struggle for replication, and in this struggle there are many casualties who don’t make it. There’s no higher intelligence out there guiding events, just the brutal struggle for survival and reproduction.

I personally find this unpersuasive, because I don’t think a narrow Darwinism is an adequate explanation for human consciousness. Our conscious rationality seems unnecessarily sophisticated for the quite simple job of survival and reproduction. It is excess to requirements. I agree with the ancient Greek philosophers that our conscious rationality means we can not merely survive and reproduce, but know ourselves, change ourselves, and find happiness and fulfilment. This Socratic optimism gives me some faith that there is a higher intelligence, and that consciousness is the fulfilment of some higher plan or programme. I also think, as Andrew Marr put it in his Start the Week interview with Sam Harris, that there is something in all of creation that loves to worship creation, to glory in its existence. Birds don’t sing purely to attract mates. That’s a narrowly Darwinian view of bird song. Sometimes birds just sing, to celebrate life and worship creation. Likewise, humans don’t dance purely to attract a mate. That’s also a narrowly Darwinian interpretation. As Lady Gaga pointed out, sometimes we just dance.

However, I don’t believe in a personal afterlife, nor do I believe in the perfection of creation. I don’t understand why one of my best friends from school has been condemned to a lifetime of paranoid schizophrenia. I don’t know why God would do that to someone.

But why do we assume God is perfect and all-powerful? Is it possible that we’re in some sort of beta version of creation, and that God is still ironing out some fairly major glitches? Is it possible that God is Himself going through various versions and upgrades – and that human consciousness is part of that upgrade?

The Stoics had a rather bleak view of the matter. They believed in a cosmic plan, and believed consciousness was a part of that plan. But they also thought that, according to the divine plan, the universe would expand until it reached a certain point, and then everything would be engulfed in flames and be sucked back into a tiny point. And then everything would explode back into creation, and the whole programme would run again, exactly the same as before. Eternal return, as Nietzsche called it. Many physicists today believe something close to this. It all seems a bit pointless and wearisome, if it’s true. It’s nicer to think that the Vikings, Jews, Christians or Marxists were right – that history is moving to some sort of grand final conclusion, and the series will end with a bang, rather than the daytime TV monotony of eternal re-runs. But then how could time and history simply end? What would we do then? What would God do, once the programme was finished?

By the by, have a listen to this great take-off of the astronomer Brain Cox, on the comedy radio show Down The Line. I like the caller at 11.34 who says whenever she looks up at the stars she just “feels a bit sick”.

Anyway, I’m getting a bit off my point. So Richard Layard, Sam Harris and others are trying to create a rational, evidence-based spirituality. Layard says he wants “a new secular spiritual culture – we need something which uplifts the spirit, inspires people and makes them feel part of something bigger than themselves”. He speaks of the west’s terrible failure to find a secular replacement for Christianity. He says: “The job of our culture should be to promote the altruistic over the egotistic parts of our personality. But so much of our public culture encourages the exact opposite – excessive individualism.”

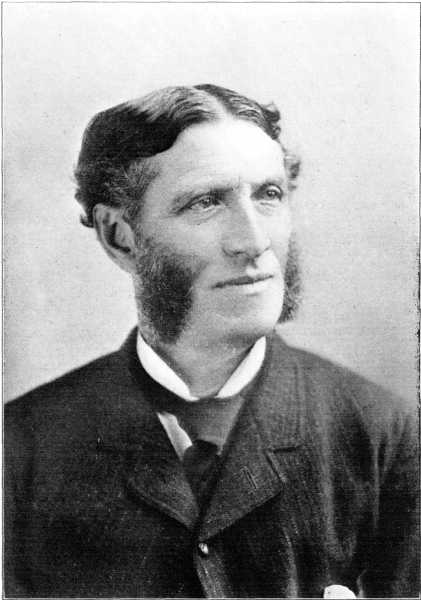

He hopes utilitarianism can become our new secular morality. He says: “I believe in Bentham.” But he thinks the 18th century, for all its enthusiasm for enlightenment and happiness, went a bit wrong, because it became “excessively individualistic”, so really he’s closer in ethos to Victorian philanthropy, though without the Victorians’ belief in “hellfire”. The person he really reminds me of is Matthew Arnold, the author of the Victorian classic, Culture and Anarchy. Both are, in their different ways, fans of Hellenic philosophy – the cognitive techniques for happiness taught by Layard’s movement, Action for Happiness, come in large part from Stoic philosophy, while Arnold’s great hero was the Stoic emperor Marcus Aurelius.

But the difference between Arnold and Layard is that Arnold thought Hellenic philosophy would only appeal to the intellectual elite, while the masses needed something more emotional, symbolic and communal – Christianity, in other words. Only Christianity, he thought, was capable of giving the masses culture and saving society from anarchy. He turned out to be wrong: British society survived the decline of Christianity without any major social revolts, thanks, I suppose, to consumerism, TV, the development of the mass leisure industry...or perhaps because of the welfare state and the increase in economic and educational opportunities for ordinary people. But that's not enough, says Layard. We need a better culture, to develop our altruistic side and free us from egotism, "the greatest cause of suffering".

It seems to me there are five challenges to this project to develop a secular, rational and evidence-based spirituality for western society:

1) What if the scientific evidence increasingly tells us that free will is an illusion, and that our lives are determined by neuro-chemical processes beyond our conscious control? That, after all, is what the neuroscientist David Eagleman argues in his new book, which I reviewed here. In that case, the science of happiness ends up with what I called an ‘amoral landscape, in which we can no longer blame anyone for their actions. The science of happiness would also end up with the mass production of happy pills. And would there be anything morally wrong with that? Would it be fine if we spent our lives blessed out on soma? I would argue that would be morally wrong, because we would have failed to develop our full potential as human beings. But it seems that, if you think the point of life is simply to experience as much happiness as possible, then the easiest way to achieve that is by taking as many happy-inducing chemicals as possible.

2) Creating a science of happiness begs the question of how you define happiness. Is happiness one single, homogenous thing, as happiness measurers say it is, or are there many different types of happiness, with some types of happiness perhaps ‘better’ than others? Jeremy Bentham thought all happiness was equal – he would have argued that Xbox was better than poetry, because it made more people happier. John Stuart Mill disagreed, and thought that some forms of happiness were ‘higher’ and ‘better’ than others. He thought poetry was better than Xbox, and therefore we should educate people to appreciate these higher forms of well-being. But if you think that’s true, then happiness measurements are simplistic and reductionist, because they don’t differentiate between different types of happiness – which jeopardises the whole ‘science of happiness’. I asked Layard, at his RSA talk, whether he agreed that Xbox was better than poetry. He thought it was, as the Evening Standard reported here.

3) The science of happiness can be just as naïve and myopic in its use of ‘evidence’ as Christians can be with their talk of miracles. Layard argues that the evidence is clear that the best way to be happy is to be nice, good, and socially progressive. But, as Andrew Marr said in his interview with Layard at the RSA, you could equally use the evidence to argue for quite a different society. Marr pointed out that the societies typically held up as happiest – the Scandinavian countries – don’t just have the biggest welfare states, they are also typically the most ethnically homogeneous societies, and that’s why “Danes and Swedes are readier to contribute where only Danes and Swedes get the goodies”. People are prepared to pay more taxes when the people receiving social benefits are from their own culture and race, who they appear to trust more. There’s also evidence from Robert Putnam that the least happy communities in the US are the most ethnically diverse – because people trust each other less in such societies. Now you can make other arguments in favour of multicultural societies – that they are more just, or economically stronger. But the ‘science of happiness’ might actually suggest we live in smaller, more conservative, more religious and less ethnically diverse societies. I'm not saying we should live in such societies. I'm saying that if we religiously followed the happiness evidence, that's where it might lead us.

4) There’s a limit to what science can tell us. We can never exactly be sure what constitutes the Good Life, and can never create a perfect science of well-being, because we can’t really be sure why we’re here, or what happens to us after we die, or if there’s a God. There’s an inescapable uncertainty about the point of human existence, which science cannot eradicate – and I don’t think it ever will.

5) Finally, most importantly, rational science – like rational philosophy – lacks the strong emotional, communal, symbolic and ritualistic power of the major religions. Marr, again, made this point well to Sam Harris – he said, if I remember right, “do you have an army of chaplains ready to spread your new morality across the world?” And of course, he doesn’t, and neither does Layard. The science of happiness lacks what Simon Jenkins unhappily called an ‘infrastructure of joy’. Action for Happiness has fewer followers than the Jedis. There are no happiness centres, no secular churches, no songs, no myths, no narratives, no martyrs, no rituals, no holy days. Nothing to connect our rational prefrontal cortex to the deeper limbic springs of our being. Nothing to bring us together to combat the great sickness of modern times: loneliness.

The challenge is to create new forms of togetherness, new forms of culture. But it’s also to incorporate older forms of culture, including religious culture, into a harmonious multicultural society. Because right now, the best cultures for happiness that we have are, according to the evidence, religious cultures – although unfortunately these religious cultures seem to be rather exclusive and intolerant of each other. I hope Hellenic philosophy can become a meeting ground both for religious cultures like Catholicism, Islam and Judaism, and for the secular science of happiness – because all these cultures draw on Hellenic philosophy (particularly Aristotle, but also the Stoics) and use similar ideas and techniques. But any revival of ancient philosophy faces the same problem as utilitarianism or the science of happiness: a lack of communal rituals and forms of togetherness.

We tried to make Marcus Aurelius' birthday (on April the 26th) a new special day for fans of Stoicism, and held our first Aurelius conference in San Diego last year. But the event will go uncelebrated this year - an attempt by me to hold a similar event in London attracted little enthusiasm from other Stoics. Instead, next month I'll go to Hay-On-Wye, and to the How the Light Gets In festival, to hold a workshop with the London Philosophy Club, and see if we can take another step towards developing a popular mass philosophy - one which doesn't charge £30 for every service. Come and join us - the event is on Tuesday May 31st, at 10.30.

Anyway, I wish you a very happy Easter weekend, and hope that you find your own forms of togetherness with loved ones this weekend.

Jules