PoW: On revolutionary Aristotelianism

One of the most influential modern philosophers is the Neo-Aristotelian Alasdair MacIntyre, who helped kick-start the revival of virtue ethics and the politics of flourishing in contemporary political thought. He is cited everywhere: in the MP Jon Cruddas' call for Labour to embrace a 'politics of virtue', in Maurice Glasman's Blue Labour, in Philip Blond's Red Toryism and the Big Society, even in David Brooks' dubious brand of neuro-politics.

One of the most influential modern philosophers is the Neo-Aristotelian Alasdair MacIntyre, who helped kick-start the revival of virtue ethics and the politics of flourishing in contemporary political thought. He is cited everywhere: in the MP Jon Cruddas' call for Labour to embrace a 'politics of virtue', in Maurice Glasman's Blue Labour, in Philip Blond's Red Toryism and the Big Society, even in David Brooks' dubious brand of neuro-politics.

Sadly for us Brits, MacIntyre left these shores several years ago to teach at the University of Notre Dame, home of many other eminent specialists in Catholic philosophy (MacIntyre calls himself a Thomist Aristotelian, meaning that he prefers Thomas Aquinas' version of Aristotelianism to Aristotle's version). But today, we got a rare chance to see him talk, at the London Metropolitan University, where he was promoting a new collection of essays by him and other academics called Virtue and Politics: Alasdair MacIntyre's Revolutionary Aristotelianism.

I asked him what he thought of the many different contemporary thinkers, like Glasman, Blond and Brooks, who cite both Aristotle and himself for their various political programmes - and what he thought a contemporary Aristotelian politics should look like.

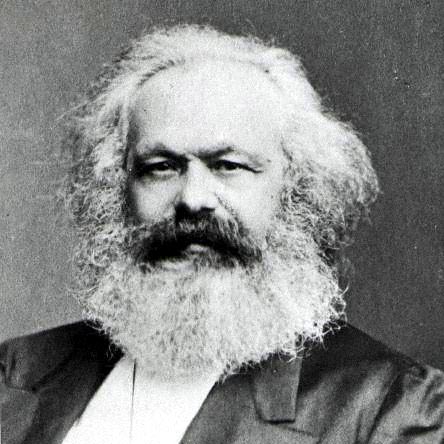

He replied: 'What Aristotle provided us with is a scheme in which to understand the existence and attainment of individual and common goods. When we look at contemporary societies, we see that they don't achieve these common goods. Why don't they? If Aristotle is right, then something has gone horribly wrong. If something hasn't gone horribly wrong with contemporary societies, then Aristotle is irrelevant. The people you mentioned think something must be done in contemporary societies, but they don't think the change should be root-and-branch. The thinker who did understand the need for root-and-branch change was that great Aristotelian, Karl Marx. He provides the first and best account of what prevents an Aristotelian society."

He replied: 'What Aristotle provided us with is a scheme in which to understand the existence and attainment of individual and common goods. When we look at contemporary societies, we see that they don't achieve these common goods. Why don't they? If Aristotle is right, then something has gone horribly wrong. If something hasn't gone horribly wrong with contemporary societies, then Aristotle is irrelevant. The people you mentioned think something must be done in contemporary societies, but they don't think the change should be root-and-branch. The thinker who did understand the need for root-and-branch change was that great Aristotelian, Karl Marx. He provides the first and best account of what prevents an Aristotelian society."

After the talk I had a look at MacIntyre's interesting opening essay in Virtue and Politics, which is called 'How Aristotelianism can become revolutionary.' He writes that several institutional aspects of contemporary society make a genuine politics of human flourishing very difficult today. Firstly, the nature of modern life leads to the compartmentalization of the self into several different roles, each with their different moral agendas (you could be a different person with different values at work to who you are at home, for example, like Wemmick in Great Expectations), which obstructs the Aristotelian question of what is the good life for me as a whole person.

"The question substituted [MacIntyre writes] is 'what do I feel about my life?' or 'Am I happy or unhappy?' One consequence of this is that we have now in academic life a growing happiness industry...[But] what matters is not so much whether people do or do not feel happy about their lives, but whether they have good reason to feel happy or not about them. Most important of all, this focus on psychological states once again gets in the way of asking Aristotelian questions."

Secondly, the capitalist economy gets in the way of asking Aristotelian questions about the good life. "We inhabit a social order in which a will to satisfy those desires which will enable the economy to work as effectively as possible has become central to our way of life, a way of life for which it is crucial that we desire what the economy needs us to desire. What the economy needs is that people become responsible to its needs rather than their own, and so it presents as over-ridingly desirable those goals of consumption and ambition, the pursuit of which will serve the economy's purposes. The desires to achieve these goals, when they become central to our lives, prevent us from becoming self-critical about our desires, and so prevent the asking of Aristotelian questions about character and desire."

Secondly, the capitalist economy gets in the way of asking Aristotelian questions about the good life. "We inhabit a social order in which a will to satisfy those desires which will enable the economy to work as effectively as possible has become central to our way of life, a way of life for which it is crucial that we desire what the economy needs us to desire. What the economy needs is that people become responsible to its needs rather than their own, and so it presents as over-ridingly desirable those goals of consumption and ambition, the pursuit of which will serve the economy's purposes. The desires to achieve these goals, when they become central to our lives, prevent us from becoming self-critical about our desires, and so prevent the asking of Aristotelian questions about character and desire."

Thirdly, modern capitalist economies lead to "conditions of gross inequality: inequality of money, inequality of power, inequality of regard, and it is an undeniable fact that even the most successful examples of growth in the present globalised economy generate further inequalities. Aristotle pointed out long ago that a rational polity cannot tolerate too great inequalities, because where there are such, citizens cannot deliberate together rationally. They are too divided by sectional interests so that they lose sight of the common good."

So what does that mean for us today? If our society requires a root-and-branch revolution for us to achieve our basic individual and common goods, does it necessitate some kind of mass revolutionary organization like the Communist Party? MacIntyre's vision is more local:

"Everything turns on the kind of projects in which plain people may get involved. Here I can give only one example, but there are many others. From time to time, it becomes possible in some local community either to bring into being a new school or to remake some existing school so it can provide an education for the children of that community. If such an opportunity arises, it is sometimes possible for parents, teachers, and other interested members of the community to become involved, and to participate in discussion and decision-making. In so doing, they become unable to avoid such questions as 'what kind of school do we construct for our children?', and 'what do we want our children to learn?' We also have to ask 'what do we take the goods of childhood to be?', and 'how, in achieving the goods of childhood, can our children be prepared to achieve later on the goods of adult life?'

MacIntyre goes on that, when you try to set up this sort of project, "you find almost immediately that you encounter the systematic resistance of the representatives of the larger social and economic structures...When we try to achieve the human good there is going to be entrenched resistance to it."

"You will be told by those who represent established power, the kind of institutions you are trying to create and sustain are simply not possible, that you are unrealistic, a Utopian. It is important to reply by saying, yes, that is exactly what we are - this Utopianism of those who force Aristotelian questions upon the social order is a Utopianism of the present, not of the future...The present is what we are and have, and the refusal to sacrifice it has to be accompanied by an insistence that the range of present possibilities is always far greater than the established order is able to allow for. We need therefore to acquire transformative political imagination, one that opens up opportunities for people to do the kind of things they had hitherto not believed they were capable of doing, and this can happen when someone becomes involved for the first time in community organizations and actions, when parents become involved in some community that sustains their children's school in the inner city, or when unorganized workers struggle to create a union, or when immigrants become involved in forms of communal enterprise that enable them to resist attempts to treat them as no more than a disposable labour force."

Interesting stuff eh? Sorry for such long quotes, but this won't be reported anywhere else so I thought it worth simply passing on. I like his idea of a revolutionary politics of flourishing very much - but I also see a lot of room for multiple competing interpretations of this politics of the common good. For example, Toby Young might think he is a revolutionary Aristotelian when he tried to set up a free school in his community, while the National Union of Teachers see such efforts as attempts to undermine their own status as organized workers. And a committed Marxist might dismiss all these local efforts as ineffectual without a broader global vision of justice. We might quote MacIntyre back at him, and accuse him of making small local changes within capitalist society without any systematic programme for 'root-and-branch' reform. In any case, much to think about.

Interesting stuff eh? Sorry for such long quotes, but this won't be reported anywhere else so I thought it worth simply passing on. I like his idea of a revolutionary politics of flourishing very much - but I also see a lot of room for multiple competing interpretations of this politics of the common good. For example, Toby Young might think he is a revolutionary Aristotelian when he tried to set up a free school in his community, while the National Union of Teachers see such efforts as attempts to undermine their own status as organized workers. And a committed Marxist might dismiss all these local efforts as ineffectual without a broader global vision of justice. We might quote MacIntyre back at him, and accuse him of making small local changes within capitalist society without any systematic programme for 'root-and-branch' reform. In any case, much to think about.

In other news (very briefly):

Martin Seligman, founder of Positive Psychology and a sort of Aristotelian, is giving a talk at the RSA on 6th July on his new book, Flourish.

Filip Matous and I from the London Philosophy Club spent the weekend at the How The Light Gets In festival, and ran a workshop on Street Philosophy. Thanks to everyone who came along, we really enjoyed it.

The Philosophy Shop, which teaches philosophy in schools, is holding an event at the LSE on the 23rd of this month, with Anthony Seldon, Philip Blond, and Angie Hobbs talking.

One way that philosophy gets taught in schools, outside of the curriculum, is through the Gifted and Talented scheme for extra-curricular studies. I am sorry to hear (rather belatedly), that the scheme has been scrapped last year. Apparently there is now no money for state-schools to run extra-curricular classes (thanks to the banks), although academies still have both the cash and the curricular flexibility to bring in extra classes in things like philosophy.

I wonder if there is a way to secure private funding (eg from banks and hedge funds) for extra-curricular classes for state schools (rather than just academies)? Or perhaps what is needed is simply an organization that puts in touch people who want to volunteer with schools looking for visiting speakers. Apparently Evan Davis of the BBC is looking to set up this sort of network. If anyone knows more about it, I'd love to hear.

Finally, here's a nice piece in the Bookseller, announcing the deal I have finally secured for my first book, Philosophy for Life. It's with Rider Books, an imprint of Random House. Thanks to my new agent, Jon Conway, for getting me the deal. I also owe a lot to the commissioning editor at Rider, Sue Lascelles, who read my manuscript when I sent it in to The Literary Consultancy and paid them to read it and give me feedback. Sue, who freelances as one of the TLC's readers, read my proposal, gave me some great feedback, and said she thought Rider Books might be interested in it. A few weeks later, she had got me a deal with Rider, and she'll be editing my book over the next few months before publication in May 2012. Thanks Sue, and thanks to TLC, who I highly recommend for those authors struggling to get an agent or a deal.

See you next week,

Jules